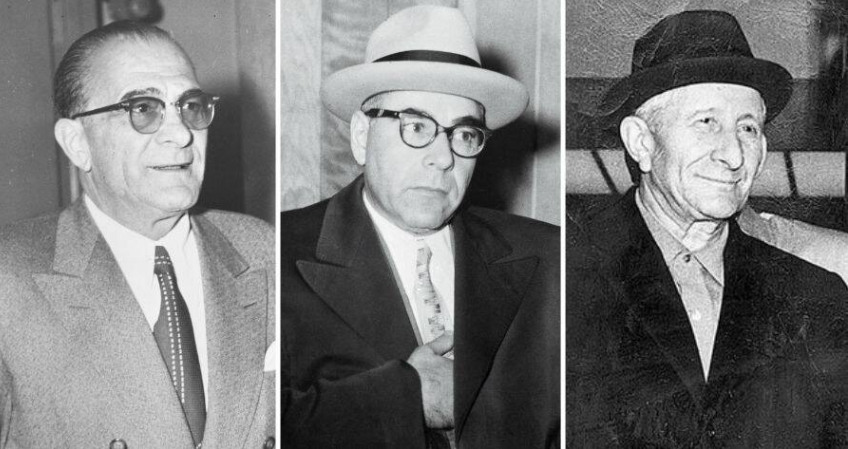

On a cold November day in 1957, over sixty of the most dangerous men in America gathered in the sleepy hamlet of Apalachin, New York. They weren’t there for a picnic, though that’s the story some tried to push. These weren’t PTA dads or Elks Lodge members. These were capos, bosses, enforcers—the bloody heartbeat of organized crime. They parked their Cadillacs in the muddy grass outside mobster Joe Barbara’s home, clinked glasses over espresso, and carved up America like it was Sunday dinner.

Then it all went sideways.

Local law enforcement, acting on little more than gut instinct and a lot of suspicious license plates, surrounded the property. What followed was a panicked stampede through the woods—mobsters ditching silk suits and Ferragamos to crawl through brush like frightened animals. Some were arrested. Most escaped. But the myth of the Mafia’s nonexistence? That didn’t survive.

But here’s the real kicker: within weeks, Washington and the FBI weren’t trumpeting victory. They were ducking, dodging, and rewriting the script. Because the truth was never supposed to get out. And if it did, they had a fallback plan.

“There Is No Mafia.”

For decades, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover treated the Mafia like a bedtime story told by frightened immigrants. He had his reasons. Publicly acknowledging a national organized crime syndicate would raise uncomfortable questions about why the Bureau had done nothing about it. Worse, it would expose the cozy relationships between politicians, law enforcement, and the underworld.

So Hoover did what any good magician would do—he redirected your gaze. With Apalachin threatening to blow the illusion apart, Hoover went into full “Wag the Dog” mode. The message to America was clear:

“There is no Mafia. There’s a local crime problem. There’s a Communist threat. There’s a youth gang epidemic. But a nationwide criminal conspiracy? Just Hollywood fantasy.”

It was misinformation wrapped in bureaucracy, sold by straight-faced agents, and swallowed by a press more interested in Reds than racketeers.

The Communist Smoke Screen

The Cold War gave Hoover all the smoke he needed. Communism, he insisted, was the true enemy. Not Italian men in Brioni suits extorting unions and assassinating rivals. No, it was the boogeyman in Moscow pulling the strings.

He redirected Bureau resources toward rooting out “un-American activity,” targeting civil rights leaders, academics, and Hollywood writers while downplaying the fact that literal crime summits were happening in upstate New York. Hoover’s priorities were political survival and public relations, not justice.

In FBI memos following Apalachin, Hoover barely mentioned the Mafia, instead authorizing aggressive expansion of surveillance operations against “subversive elements”—code for Communists, leftists, and anyone challenging the status quo. That meant bugging professors, not Mafia hangouts. That meant smearing MLK, not tailing Joe Bonanno.

Blame It on the Kids

Then came the “youth gang” epidemic. Headlines exploded with tales of knife-wielding teens, leather jackets, and switchblades in schoolyards. Juvenile delinquency became the new enemy, perfectly timed to distract from the real gangsters—men with gray hair, Rolexes, and private jets.

Hoover leaned into the narrative. The FBI issued public service announcements warning parents about Rebel Without a Cause-style miscreants. America’s suburban families were told to fear the slick-haired kid on the corner, not the Mafia boss paying off their mayor.

It was strategic. The mob was invisible. Youth gangs were everywhere. And if the public believed the biggest threat was Johnny lighting cigarettes behind the gym, they wouldn’t ask questions about who controlled the ports, the unions, the Teamsters, and half the casinos in Nevada.

Meanwhile, the Mafia Was Thriving

The Apalachin Meeting wasn’t just a dinner—it was a board meeting for the American underworld. Topics on the table included narcotics distribution, territory disputes, and whether to allow expansion into Las Vegas. It was proof—physical, undeniable proof—of the Mafia’s nationwide structure. It should have been the FBI’s Pearl Harbor moment.

Instead? Hoover called the gathering “a local matter,” dismissing it as an anomaly. Federal follow-up was slow, bureaucratic, and intentionally under-resourced. Most of the arrested mobsters were released within days. Charges evaporated like cigarette smoke.

And while the FBI chased kids in leather jackets and Reds under the bed, the Mafia went back to work, emboldened and unchecked.

The Press Played Along

Here’s the dark irony: the American press largely parroted Hoover’s framing. Mainstream newspapers ran a few splashy headlines about Apalachin, then moved on to the next Cold War scandal. Most didn’t push the question: Why were all these men meeting? Or why hadn’t the FBI prevented it?

This wasn’t just journalistic oversight. It was convenience. Hoover controlled media access like a mob boss controls street corners. Journalists who pushed too hard on organized crime found themselves frozen out—or worse, targeted. Hoover even maintained secret files on reporters.

So the narrative held: the Mafia wasn’t real. Communism was. Youth gangs were. Local corruption? Maybe. But a transcontinental criminal empire pulling strings from Chicago to Havana?

“That’s just the movies, sweetheart.”

A Hole in the American Memory

Today, the Apalachin Meeting is treated as a historical oddity—an amusing footnote in Mafia lore. But it was so much more. It was the moment the American government had the chance to rip the veil off organized crime. And instead, it blinked.

Hoover’s decision to downplay Apalachin wasn’t just cowardly. It was calculated. By shifting the national conversation, the FBI created a smokescreen that allowed the Mafia to flourish for another decade. That decision cost lives. It cost trust. And it cost justice.

It was, in every sense, a “Wag the Dog” moment. But this time, the enemy wasn’t fabricated. He was wearing a fedora and counting your money.

Final Thought: The Real Show Was Offscreen

In Wag the Dog, a fictional war distracts Americans from a Presidential scandal. In 1957, real blood on American streets was overshadowed by a war that was mostly political theater. The FBI didn’t just misdirect attention—they manufactured a different threat to keep the real one in the shadows.

The lie wasn’t that crime existed. The lie was who we were told to fear.

And in that darkness, the Mafia thrived.