In the smoky alleys and political backrooms of mid-20th-century Missouri, Charles Binaggio’s name evoked equal parts fear and fascination. He was not just a gangster—he was a dreamer, a kingmaker, a man who tried to straddle two worlds: crime and politics. And for a time, it looked like he might succeed. But like many who dare to challenge the entrenched powers of organized crime, Binaggio died not with a bang, but with four bullets to the head and his blood soaking the floor of a political clubhouse he once ruled.A Son of Two Worlds

A Son of Two Worlds

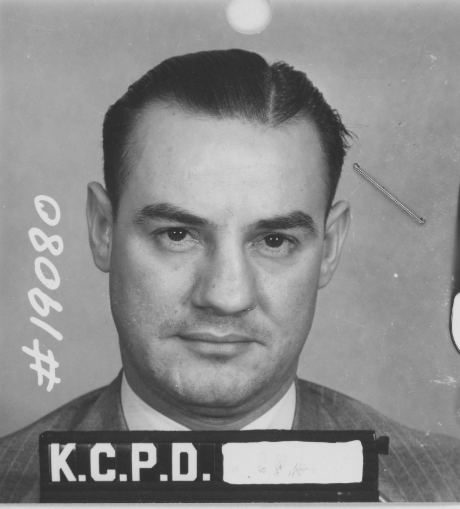

Born in Beaumont, Texas, on January 12, 1909, Charles Binaggio moved to Kansas City at a young age. Raised among Sicilian immigrants on the city’s gritty North Side, Binaggio found his calling not in school or honest labor, but in the shadows—gambling halls, speakeasies, and backroom deals. By his early twenties, he had already earned his first arrest in Denver, Colorado, during a violent turf war between crime families. The charge was weapons possession, later reduced to mere vagrancy—a footnote in what would be a long dance with the law.

His rise was swift. By 1931, Binaggio was present during a deadly shootout at the mob-run Lusco-Noto Flower Shop in Kansas City that left a Prohibition agent and two others dead. Though not charged with the killings, his proximity to the violence underscored a truth that would define his life: Binaggio wasn’t just adjacent to power—he was learning how to wield it.

The Political Gambler

After the death of his mentor, Johnny Lazia, in 1934, Binaggio quietly worked his way up the ranks. Under Charley “The Wop” Carollo, he became underboss, and when Carollo was imprisoned in 1939, Binaggio assumed the top job in the Kansas City crime family.

But Binaggio wasn’t content with the typical vices of mobsters—bootlegging, gambling, narcotics. He had a grander vision: to marry the muscle of the mob with the machinery of politics. He established the First Ward Democratic Club and began building his own political machine, carving out territory from the powerful Pendergast dynasty that had long ruled Kansas City politics.

He didn’t just want influence—he wanted control.

Governor for Sale

By 1948, Binaggio believed he had found his golden ticket. Forrest Smith, a Democratic candidate for Missouri governor, needed money and political support. Binaggio had both. With funding from La Cosa Nostra—reportedly as much as $2 million—he helped Smith win the election, expecting a massive return on investment: control of the Kansas City and St. Louis police departments. The goal was simple: legalize and protect the mob’s gambling empire in Missouri.

But Smith, perhaps sensing the weight of what Binaggio demanded, backed out. Though he made a few appointments to the city’s Board of Police Commissioners, he never handed Binaggio the keys to the kingdom. The mob-backed gambling parlors—once brimming with promise—went dark.

For the syndicate bosses in Chicago and New York, this was unforgivable. Binaggio had failed to deliver.

The Last Call

The warning signs were there. Binaggio, usually calm and calculating, became reckless—desperate. He tried to bribe police commissioners. He threatened others. He leaned harder into the politics that had once been his path to legitimacy. But nothing worked. The criminal elite—men with longer shadows than his—had seen enough.

On April 6, 1950, Binaggio and his volatile underboss, Charles “Mad Dog” Gargotta, were summoned to the First Ward Democratic Club. Binaggio told his driver, Nick Penna, to wait for him at the Last Chance Saloon. “Just a quick meeting,” he said.

They never returned.

At around 8 P.M., gunshots rang out from the club. It wasn’t until 4 A.M. that a cab driver noticed the door ajar and water running inside. Police found the two men dead—Binaggio slumped over a desk, Gargotta collapsed just inside the front door. Both had been executed with four shots to the head, likely from .32 caliber revolvers. The crime was professional. Cold. Final.

A broken toilet was the only sound left in the room when the police arrived.

Who Pulled the Trigger?

Speculation ran wild. Did the killers come from Chicago? St. Louis? Or were they local—friends turned traitors, obeying orders from the Mafia Commission in New York? Most believe the execution was sanctioned at the highest levels. Binaggio had cost the mob millions and threatened their credibility. He had dreamed too big and failed too loudly.

Some believe Anthony Gizzo, his old friend and Denver cellmate, orchestrated the hit. Days later, Gizzo emerged as the new boss of the Kansas City family—a promotion bought not with merit, but with murder.

A Legacy in Blood

More than 1,200 mourners filled Holy Rosary Church for Binaggio’s funeral. Ten thousand more lined the streets as his body was carried to Mount Saint Mary’s Cemetery—just yards from the grave of his old mentor, Johnny Lazia. Sixteen years earlier, a tearful Binaggio had helped lower Lazia’s coffin into the earth. Now, his own journey ended in nearly the same spot—violent, unresolved, unfinished.

Binaggio died at 41, having reached for something greater than most mobsters dared. He wanted legitimacy, power, and recognition beyond the underworld. But in doing so, he forgot the first rule of the Mafia: never outshine the system.

Charles Binaggio wasn’t just a casualty of ambition—he was a warning. A lesson whispered in smoke-filled rooms and remembered in bullet holes and bloodstains. In the world of organized crime, failure is not forgiven.

And kings who forget that rule don’t get to die old.

Written by C.F. Marciano