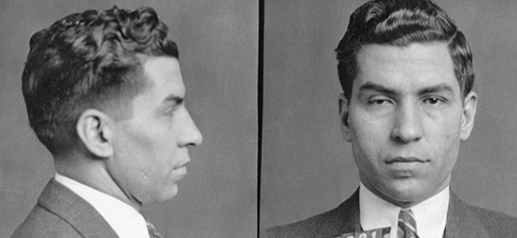

In the smoky twilight of post-World War II Europe, a specter crept across the Mediterranean and into the alleys of New York, Chicago and Miami. Its architect was Charles “Lucky” Luciano—once the kingpin of New York’s organized-crime world—now steering a far darker, more insidious enterprise from his exile in Italy. Deported in 1946 after a wartime deal, Luciano did not vanish. Instead, he pivoted to forge the prototype of the global heroin trade, linking the poppy fields of the Middle East, hashish labs of southern Europe, and the drug-hungry streets of the United States.

From Bootlegging to International Narco-Business

Luciano’s early career is well known—bootlegging, brothels, the formation of the “Commission”, and the New York structure of the Mafia. But his exile to Italy did not mark retirement—it marked an escalation. After the war, American authorities commuted his sentence in recognition of supposed wartime services. He arrived in Italy constrained—but far from powerless.

From Naples and Palermo he orchestrated a far-flung web of narcotics trafficking. As one blogger put it, “Within two years of his arrival in Italy, Luciano had not only rebuilt his empire but transformed it into a narcotics operation of unprecedented scale.”

The method: Raw opium and morphine base flowed from Turkey or the Middle East to Lebanon; then shipments sailed to Sicily or France (especially Marseille) for processing into heroin; finally, the finished packets were smuggled into the United States via shipping containers, fruit crates, and even diplomatic or courier cover-routes.

Key Players & Routes

- Luciano himself remained the shadow king: from Italy, he coordinated smuggling channels, and set finance and policy in motion.

- Meyer Lansky, the Jewish-American syndicate brain, handled monies, laundering, and connections in New York and Cuba, working in concert with Luciano’s European operations.

- Santo Trafficante Jr. and the Florida/Cuba rackets enabled the Caribbean leg of the trade—shipments from Europe or North Africa could be rerouted through Havana, Miami, Tampa, then into the U.S. interior.

- Italian and Corsican-French actors: In Sicily, men like Calogero Vizzini or the Greco clan managed the operatives on the ground; in Marseille, the compact but efficient “French Connection” labs processed the goods.

- Government officials and customs agents (sometimes complicit). Evidence suggests the clandestine shipments started within months of Luciano’s deportation.

The Business Model: Efficiency, Corruption & Violence

What made the post-war operation distinct was its corporate logic. Luciano had pioneered the modern mob model—diversified rackets, centralized rule, and ruthless efficiency. Now the model applied to heroin. In a blog summary:

“The network funneled morphine base from the Middle East, refined it into heroin in clandestine Sicilian and Marseille laboratories, and flooded the streets of America with an ever-growing supply.”

This operation worked because:

- Raw materials were stockpiled in unpredictable jurisdictions.

- Processing shifted as pressure mounted (Sicily → Marseille → Corsica);

- Smuggling routes were disguised in legal cargo (fruit, textiles, machinery) and layered through transit zones to avoid inspection.

- Bribery, intimidation and murder kept port officials, police and union leaders in line.

- On the receiving end, U.S. distribution networks (New York, Chicago, Detroit) worked through the apparatus Luciano had built in the 1930s.

The Myth of Blame & the Excuse for Violence

While the shadow syndicate moved tons of heroin, the public narrative simplistically demonized other states or countries as the “top” drug importers or exporters—often without empirical backing. This narrative served as a justification: if country X is the “worst importer of illegal drugs worldwide”, then deadly force can be rationalized under the guise of “anti-narco warfare”. But the real trade lanes spun by Luciano were far less visible and far more efficient. To claim that any isolated country alone is the top importer or exporter obscures the multilayered networks that he built and manipulated—even from exile.

This false premise enables a lethal logic: if one asserts that a certain nation leads the trade, one may claim unlimited war-powers or sanction authority. But when the real architecture of trafficking stretches from the poppy fields of Anatolia, through Lebanon, Sicily, Marseille, Florida, and into U.S. cities, then the simplistic justification collapses. The story of Luciano’s network shows how invisible the infrastructure truly is—even as it kills thousands of addicts, devastates communities, and corrupts officials.

Consequences & Legacy

By the time Luciano died in 1962 at the airport in Naples, the heroin trade was already globalized and diversified—and his blueprint was embedded in almost every major trafficking organization.

The legacy is grim:

- Addiction rates in the United States soared in the 1950s and 1960s.

- Law-enforcement struggled to follow the money or trace the supply chain because it spanned countries and involved semi-legal cover businesses.

- The myth-making around “which country is the worst” distracted from the real architecture of predation: organized crime working with rogue states, corrupt officials, and weak international coordination.

- The structure that Luciano helped create—smuggling by sea and air, processing abroad, laundering through legitimate business—remains the template for modern narcotics networks.

Conclusion

Charles “Lucky” Luciano did not retire into obscurity; from his base in Italy he masterminded a narcotics empire that linked continents, financed politics, corrupted ports and ruined lives. The story of the drug trade after the war is not one of simple blame or obvious borders—it is a dark tapestry of global supply-chains, hidden labs, and silent deals. And when public discourse singles out one nation as the “top importer” in order to justify violence or extraordinary measures, it ignores the subtler, more deadly truth: the real origin of the trade was built in halls, docks and clandestine factories commanded by men like Luciano—untouched by the loud rhetoric of war.