Deep in the humid soil of Newark, New Jersey, where the American dream once blossomed for immigrant families, there thrived a darker legacy — fertilized not by hope, but by fear, blood, and bodies. At the center of it all stood one man: Ruggiero “The Boot” Boiardo, a name whispered with equal parts awe and terror. He was not merely a mobster. He was a symbol of old-world brutality in a new-world empire. His backyard wasn’t just a garden — it was an open-air graveyard.

They said getting an invitation to “The Boot’s” garden meant one of two things: you were about to be honored, or you were about to be erased.

Most knew the difference too late.

From Sicily to Ironbound

Born in Naples in 1890 (despite some claims of Sicilian blood, which he encouraged), Ruggiero Boiardo emigrated to America at a time when the streets of New Jersey were teeming with promise and prejudice. Italians were treated as second-class citizens, and many, like Boiardo, found that the only real upward mobility came at the business end of a blackjack or a pistol.

He began with bootlegging during Prohibition. They called him “The Boot” not only because of his rum-running days but also because of his favored method of torture: kicking his victims senseless with steel-toed shoes until they begged for death.

But Boiardo wasn’t a street thug for long. He was calculating and cold, capable of reading a man’s weakness like scripture. By the 1930s, he had risen to become the undisputed boss of Newark under the Genovese crime family umbrella. With the blessing of bigger bosses like Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Vito Genovese, Ruggiero ran numbers, extorted businesses, and controlled gambling dens, all from the deceptively humble sanctuary of his massive estate in Livingston, New Jersey.

And it was there, in that lavish estate surrounded by manicured hedges, roses, and a sprawling vegetable garden, that the darkest tales of “The Boot” unfolded.

The Garden of Final Goodbyes

To the untrained eye, Boiardo’s property looked like paradise. There were imported statues from Italy, koi ponds, even peacocks. But in the far corner of the garden stood a simple wooden chair under a tree — known by insiders as the “Death Seat.”

Victims were brought there, often under the pretense of having a personal meeting with the don. It was a compliment to be summoned. Many thought they were getting a promotion, a bigger piece of action, a deeper trust from the old man himself. But what they got instead was the slow realization — usually too late — that they had already been judged.

Some say Boiardo insisted on looking his victims in the eye before ordering the final blow.

Others whisper that he offered a glass of wine first.

And in the most chilling stories, the victims thanked him for the meeting.

They called it a “privilege” to die in his presence — such was the twisted loyalty and fear he inspired.

A Legacy of Brutality

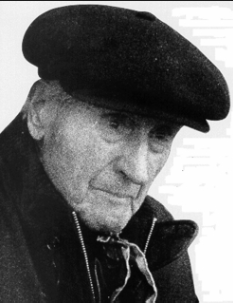

Ruggiero’s style wasn’t flashy like some of his counterparts. He didn’t wear loud suits or run nightclubs. He wore dark, well-tailored clothes and spoke in soft, almost grandfatherly tones. But his reputation for cruelty was legend.

He once strangled a bookmaker with his own necktie in front of dinner guests for skimming. Another time, he had a man buried alive for giving information to federal agents — allegedly planting flowers over the grave the same afternoon.

The Boot ruled with absolute authority, and his crew followed his example.

They carved out a criminal empire in Essex County, making Newark one of the most dangerous cities in the country by the mid-20th century. Construction unions, vending machines, bars, political contracts — all fell under the shadow of Boiardo’s influence.

But it was the murders that cemented his legacy. Not just because of how many people died under his rule — but because of how they disappeared. Bodies never surfaced. Wives never had funerals. Children grew up asking where Daddy went. The garden saw to it all.

The Boot and the Law

Despite decades of suspicion and surveillance, Boiardo was never successfully prosecuted for murder. His only major legal issue was a 1957 tax evasion case that briefly landed him in federal prison.

He beat every rap like a man swatting away flies.

The FBI referred to him as “one of the most dangerous men in New Jersey”, yet could never penetrate his inner circle. Informants were few and short-lived. Witnesses recanted or vanished.

His political connections ran deep. Local judges, cops, and city officials all feared and respected him. Newark mayors were said to quietly meet with him before elections. If you wanted to build something, you asked The Boot first — or you didn’t build at all.

Decline and Death

By the late 1960s, age and federal pressure finally began to erode Ruggiero’s empire. Younger, flashier mobsters like Anthony “Tony Bananas” Caponigro and Vincent “The Chin” Gigante started making moves, and the Boot’s name became more legend than presence.

Still, no one dared cross him directly.

He died in 1984 at the age of 94, remarkably wealthy, never having spent a day in prison for violence. He was buried with honors at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in East Hanover. His headstone sits beside that of his son Richie “The Boot” Boiardo — who inherited his father’s nickname, estate, and, for a while, his power.

But the house is gone now. The garden is gone. The land was sold, bulldozed, turned into suburban developments.

Still, locals say the earth there feels… wrong.

Dogs won’t go near it. Construction workers tell stories of bones surfacing in the dirt. A few claim they’ve seen shadows where the old garden chair once stood. Some say you can still smell cigar smoke and tomato plants on summer nights.

The Devil in the Garden

The story of Ruggiero “The Boot” Boiardo is more than just mafia folklore. It’s a brutal example of how the American dream can rot from the inside when built on violence and fear.

His garden was not a place of peace, but a performance stage for his cruelty — a place where death was dressed in ritual and respect. Where power meant never having to dirty your own hands because everyone around you was already bloody.

He wasn’t cinematic like Capone or Gotti. He didn’t chase headlines. He didn’t have to.

He had something more terrifying: total control — the kind that made people weep with gratitude before they died.

And in the long, quiet shadows of that New Jersey garden, the ghosts of The Boot’s reign still whisper.

You just have to listen.