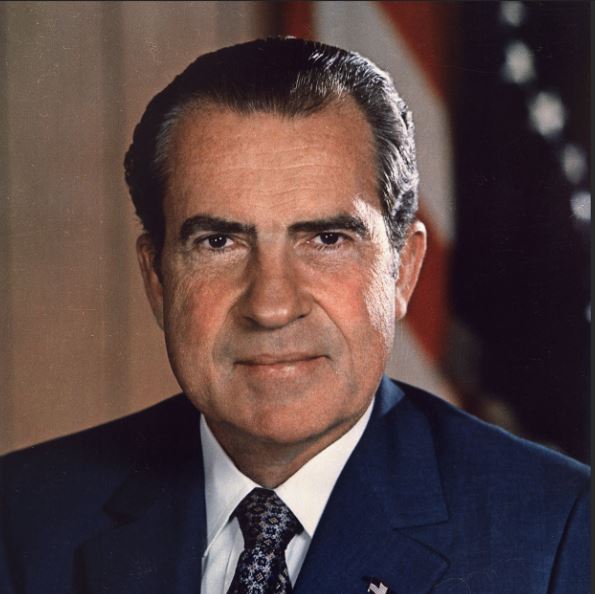

In the corridors of power, the façade is always clean. But Richard Nixon’s political legacy—often reduced to Watergate and a resignation speech—has a darker, more insidious origin story. Behind the tight-lipped grimace, the sweaty brows, and the infamous “I am not a crook” declaration, lurked a far more damning truth: Nixon’s rise was bankrolled, backed, and buttressed by the Mob.

It was Martha Mitchell, wife of Attorney General John Mitchell, who first publicly cracked the veneer. Amid the swirling chaos of the Watergate scandal, she warned a reporter, “Nixon is involved with the Mafia. The Mafia was involved in his election.” The White House spun her as a drunk, a madwoman. But history, it turns out, is on her side.

At the rotten heart of Nixon’s political machine was Murray Chotiner—a bloated, cigar-chomping mob lawyer who advised Nixon from his earliest campaigns and dressed like a gangster to match his clientele. Chotiner was more than just a consigliere in a tailored white-on-white shirt; he was Nixon’s backchannel to organized crime. As one aide would later describe him, Chotiner was Nixon’s Machiavelli—but with better connections to Jimmy Hoffa, Carlos Marcello, and Mickey Cohen.

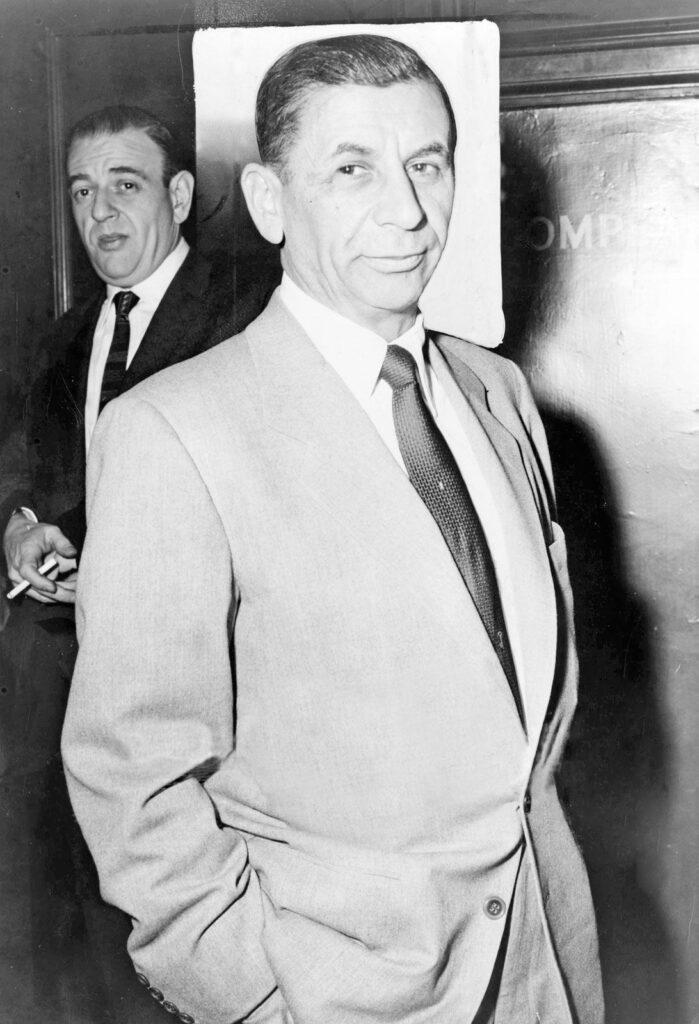

Nixon’s political ascent in 1946 wasn’t just fueled by Cold War rhetoric—it was fueled by mob money. Cohen, the flashy Los Angeles mobster, didn’t just donate $5,000 to Nixon’s first congressional race; he gave him free office space. In 1950, Cohen—under orders from Frank Costello and Meyer Lansky—threw a $75,000 fundraising dinner at L.A.’s Knickerbocker Hotel for Nixon’s Senate run. The guests were a who’s who of the Vegas gambling syndicate. “There wasn’t a legitimate person in the room,” Cohen later recalled. Exit doors were locked until the mobsters had ponied up every last dollar. And when Nixon took the podium, the mafia’s man gave them their money’s worth.

Why did the Mafia care? Because Nixon was clean—at least on the outside. As Senate crime investigator Walter Sheridan once said: “If you were Meyer, who would you invest your money in? Some politician named Clams Linguini? Or a nice Protestant boy from Whittier, California?”

Meyer Lansky, the mob’s financial mastermind, had turned Havana into a gilded playground of vice under the dictator Fulgencio Batista. Cuba, under Lansky’s stewardship and Batista’s iron fist, was the Mob’s Latin Las Vegas—except dirtier, bloodier, and far more profitable. Havana raked in $100 million a year for the U.S. syndicate, even after Batista got his cut.

And Nixon? He loved it.

In 1955, as vice president, Nixon traveled to Havana to kiss Batista’s ring. In return, he offered the dictator a U.S. medal of honor and praised Cuba for its “democratic ideals.” He returned to Washington and told the Cabinet Batista was “desirous of doing a good job.” What he didn’t mention were Batista’s massacres, political assassinations, or the fact that Lansky ran Havana’s gambling empire with the same precision he used to launder blood money through Miami banks.

Nor did Nixon disclose his own luxurious stay at Lansky’s Hotel Nacional, in the presidential suite, no less—comped, of course. He also didn’t mention that his friend Bebe Rebozo was covering his massive gambling losses—rumored to be as high as $50,000. Nixon’s Cuban jaunt wasn’t diplomacy; it was a mob-sponsored junket.

Bebe Rebozo, the sun-kissed Cuban-American banker, was more than just a close friend. He was Nixon’s fixer, his financier, his silent partner in schemes that blurred the line between politics and organized crime. Rebozo, who had deep ties to Lansky’s gambling rackets in Florida, was called by local police “one of Lansky’s people.” He didn’t just launder money—he laundered Nixon’s image.

By the time Nixon entered the White House in 1969, he had been intertwined with underworld figures for more than two decades. His political machinery ran on dirty cash, favors, and mobbed-up connections that extended from Vegas to New Orleans to Miami. In exchange, Nixon offered legitimacy, favors, and the occasional political shield from prosecution.

Consider Nixon’s entanglements with Carlos Marcello, the ruthless New Orleans boss who once allegedly had JFK on his hit list. Marcello co-owned the Beverly Club in Louisiana—with none other than Batista himself. When Nixon cozied up to Marcello’s allies during his rise to power, it wasn’t just for votes—it was to secure a seat at the high-stakes table where politics and crime converged.

Then there was Santos Trafficante, the Tampa mob boss and undisputed king of Cuban gambling. His San Souci casino was a Mob jewel. Nixon and Rebozo forged ties to Trafficante and his circle while basking in Havana’s illicit luxuries. And later, it was Trafficante’s world—Miami, Tampa, and the Caribbean—that formed the backdrop of Nixon’s post-vice-presidential political rebirth.

By the 1970s, Nixon’s criminal ecosystem was so entrenched it was practically invisible. Howard Hughes, the eccentric billionaire with Mafia ties, funneled $100,000 in secret donations to Nixon—money delivered through Richard Danner, a corrupt ex-FBI agent and Rebozo associate. It was all part of a sprawling web: Nixon, Rebozo, Hughes, Chotiner, the Mob.

This wasn’t about isolated bribes or shady acquaintances. It was systemic. And Nixon’s most enduring gift to the underworld wasn’t policy or protection—it was access. In Bebe Rebozo, the Mob found a channel straight into the Oval Office. By one estimate, Rebozo spent time with Nixon during one out of every ten days of his presidency. He wasn’t just a friend. He was the Mob’s shadow diplomat.

As Watergate brought Nixon’s presidency crashing down, few were paying attention to the deeper rot beneath the scandal. Nixon’s dirty tricks team got headlines. His Mafia patrons didn’t. But in the words of one mob insider, “If you owned Nixon, you owned America.”

History tends to focus on the crime that brings a man down. But the real crime is often the one that got him there in the first place. Richard Nixon didn’t just betray the American people by covering up a break-in. He betrayed them by selling the White House, piece by piece, to the highest bidder—and the Mob was always ready to pay.

A Creation of C.F. Marciano – The Boss Behind the Pen