It was just past the quiet hum of late-night business at the Melrose Diner on Passyunk Avenue in South Philadelphia, the kind of greasy-spoon joint where the coffee runs strong and the neon sign glows into the early hours. But on September 17, 1993, the hum of clinking dishes and the hiss of the grill were drowned out by gunfire and the crack of betrayal. Outside, parked in the lot of the diner, a white Cadillac Seville idled. Its occupant: 46-year-old bartender and neighborhood fixture Frank Baldino. The hit men rolled up. One shouted his name. The next moment the car window shattered and bullets erupted. Baldino was struck multiple times in the head and torso.

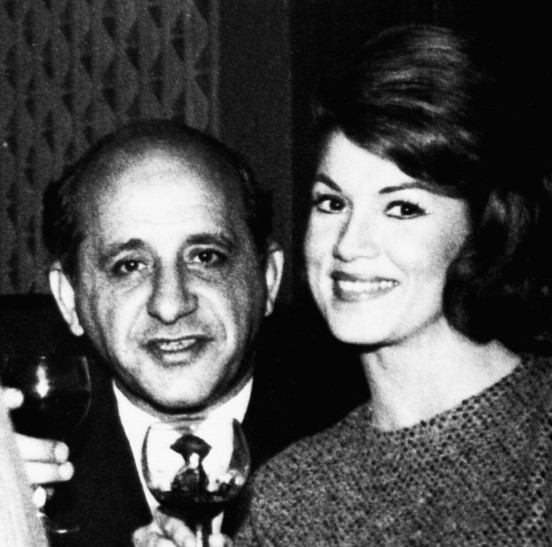

The murder of Baldino wasn’t a random act of violence. It was a statement—one more brutal salvo in the war ravaging the Philadelphia crime family. At its center were the aging boss, John Stanfa, trying desperately to hold onto power, and the rising street-wise faction led by Joey Merlino (aka “Skinny Joey”), renewing the age-old rituals of loyalty, greed, violence.

Within this war, the name of one man looms large—Frank Martines. Though much of the press doesn’t always mention him explicitly in the Melrose hit, internal mob lore and subsequent indictments indicate that Martines, aligned with Stanfa’s faction, played a critical role in the hit team that day.

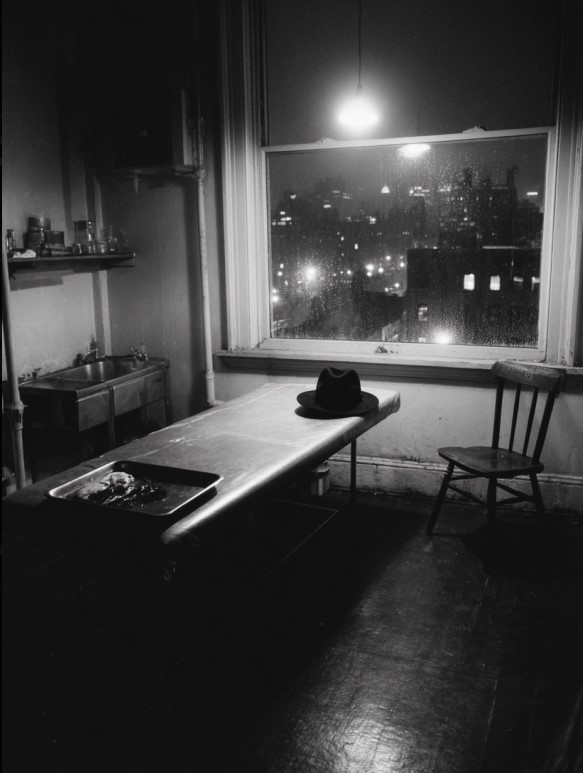

The setting and the chessboard

South Philadelphia in the early 1990s was no Sunday outing. It was a turf-war zone masquerading as everyday neighborhood. The diner itself—its chrome counters, cigarette haze, flickering lights—became ground zero. The hit team drove in, surveyed the lot, recognized the Cadillac of Baldino, and sprang into action. According to one vivid retelling by hitman turned informant John Veasey, Martines and another associate, Giuseppe Gallara, accompanied him as they waited for Baldino to finish his chopped steak dinner and exit the diner.

“Yo, Frank,” Veasey shouted at the driver, then rammed his .45 through the glass and emptied the magazine. Seven hits. The Cadillac lurched. Baldino slumped. Bullet casings scattered across the diner parking lot. The efficient violence shocked the block—quick, ruthless, public. The message read: Anyone with the Merlino crew’s colors was fair game.

Martines was no novice. He had been promoted deep inside Stanfa’s circle, trusted with enforcing discipline, managing the “Young Turks” problem (the phrase used for Merlino’s crew) and turning his contractor-waste-management legit front into muscle.

Why Baldino? Why there?

Pick a day. Sit at the Melrose. Order your steak special. Then a Cadillac pulls up, tail-lights flick off, and the barrel of a gun bursts into your window. That’s what happened. Baldino wasn’t the boss. He was a bartender, a small piece in the larger war. But his associations were fatal. He answered to Merlino’s crew—tainted in Stanfa’s eyes. The Stanfa camp decided to strike not at the head, but at the foot-soldier, to show fear, to show dominance.

Martines knew this calculus. He also knew that to survive you not only had to pull the trigger—you had to pick the place, pick the moment, then vanish. The Melrose Diner became a symbol: even in a garden of greasy spoons, no escape from the war.

The fallout

The hit did more than silence one bartender. It escalated the violence. It forced law enforcement’s gaze onto the Melrose lot. It forced allies and rivals to flip sides. Martines’ role in the shooting put him deeper in the red zone. The war sped up. Shortly afterward, Veasey turned government witness, helping build the case against Stanfa.

Stanfa was indicted in March 1994 along with 23 of his associates. In November 1995 a jury convicted him, and by July 1996 he got life. Martines would be swept into the dragnet. While varying sources conflict on exact dates and responsibility, a consistent thread: Martines was in the run-up, the party planning, the enforcing. His fingerprints may not have been on the trigger but they were on the plan.

The Melrose Diner’s legacy

Today the Melrose stands (or stood) as more than just a late-night eatery. For the mafia-blog-reader, it’s hallowed ground of blood and betrayal. A place where Parmesan on spaghetti and pool-tables and pie-crust intersected with execution-orders and bullet wounds. Even the chrome stools now seem tarnished under the weight of that moment.

The diner’s story unspools far beyond just food. It tells of loyalty corrupted, of quiet neighborhoods turned war-zones, of men like Martines who leveraged legitimate front-companies to bury illicit leadership wars. The murder left a stain. A report from the Los Angeles Times described Baldino’s death as “another attack in an escalating war for control of Philadelphia’s crime family.”

Martines: enforcer, underboss, scapegoat?

Frank Martines had it all—or so it seemed. A working-class Italian-American from South Philly, he built a contractor business, a waste-management front. He boxed. He claimed legit stripes. But the underworld doesn’t wait for permission. When Stanfa needed muscle, Martines answered. He was made acting underboss in early 1993 after the incapacitation of another capo.

The Melrose hit aligned with his remit: policing the rebellion, silencing those sympathetic to Merlino, showing Stanfa-loyal forces meant business. But in doing so, Martines stepped into a vortex of legal consequence. When Veasey flipped, Martines and others found themselves exposed. And when you ride shotgun for the boss in a battle for the throne, you equally taste the fallout.

The irony: Martines’ own survival might hinge less on his bullet-pulling and more on the machine that pulled the strings. In the end, the Melrose murder was one small move on the chessboard—but it changed the board. In the end, the murder of Frank Baldino outside the Melrose Diner becomes more than a shooting—it becomes a moment in time when the Philadelphia mob war turned public, brutal and irreversibly changed. Martines played his part. The diner witnessed it.