The Loudest Lies: Joe Colombo, Denial-as-Confession, and the Cult of “Fake News”

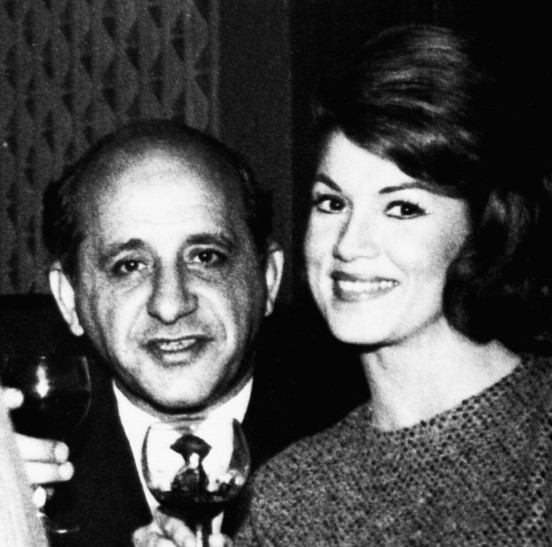

Joe Colombo was the kind of man who understood that truth could be bullied. He believed that if he shouted loud enough, insisted often enough, and smiled wide enough, he could force the world to see him as he wished to be seen—a legitimate businessman, a misunderstood Italian-American, a guy whose only sin was loving his community a little too publicly. And for a brief moment, that illusion held. Cameras rolled, crowds cheered, and Colombo played the part of the persecuted patriot.

But the louder a man screams that he’s innocent, the more the walls begin to tremble under the weight of the lie. The louder he yells “frame-up,” the clearer the outline of the frame becomes.

And Colombo—like so many men who followed this blueprint decades later—never understood that denial is its own confession.

The Professional Innocent

In the late 1960s, Colombo rose to power not only as the head of what had been the Profaci crime family but as a man who behaved as though he were the first gangster in history to discover the power of public relations.

Whenever authorities linked him to racketeering, extortion, hijacking, gambling, loan sharking—whatever the charge happened to be that month—Colombo met the cameras with the same smooth, wounded expression.

“They say I’m a Mafioso because I’m Italian.”

“They make up crimes because the FBI needs headlines.”

“It’s all lies—every last bit of it.”

No mob boss before him had leaned so heavily into “victimhood.” Others paid off cops, disappeared into safe houses, or hid behind lawyers. Colombo held press conferences.

He was, he insisted, just a man running a real estate office. Just a guy who sold greeting cards. Just a father. Just a patriot.

Just anything—anything—but what everyone in law enforcement already knew he was.

A Criminal Explains Reality to the World

Colombo’s method was always the same:

- Deny everything.

- Claim prejudice.

- Accuse the investigators of corruption.

- Redirect blame onto the media.

- Insist the truth is actually false—and the false is actually true.

This five-step survival tactic is instantly recognizable today. It has become the political operating system of an entire era—one built on the idea that if you label an uncomfortable fact “fake news,” then it vanishes. Colombo didn’t create that formula, but he weaponized it earlier and louder than most.

He was a master of the upside-down narrative:

Truth was a conspiracy. Lies were justice. Accountability was persecution.

And anyone pointing out the contradictions was, he said, part of a corrupt machine targeting Italian-Americans.

But behind Colombo’s protests lay the one detail he could never scrub clean:

He was, unequivocally, the head of a Mafia family.

Not a suspected leader.

Not a rumored leader.

The leader.

His denials were theatre—dramatic, loud, and fragile.

The Italian-American Civil Rights League: A Megaphone for a Lie

In 1970, Colombo crossed a line the old dons knew never to cross: he built a political movement around his innocence.

The Italian-American Civil Rights League—marketed as a defense against ethnic stereotypes—was in practice a billboard for Joe Colombo. And Colombo used it to push one message relentlessly:

The government lies about me. They lie about all of us.

He stormed FBI headquarters with protestors, chanting that Italian-Americans were being profiled. He pressured film studios. He attacked newspapers. He insisted that the entire justice system was corrupt, biased, dishonest.

Every accusation against him was, he said, a smear campaign.

Every indictment was a hate crime.

Every news article revealing his criminal activity was “false,” “fabricated,” “fake.”

You could almost feel him daring reality to contradict him.

The Psychology of Overprotestation

There’s an old truth psychologists understand well: the more aggressively a person denies an accusation, the closer that accusation is to the nerve.

Colombo’s entire personality was built around overprotestation.

If someone accused him of running rackets, he’d hold a rally.

If agents subpoenaed him, he’d schedule a press conference.

If the newspapers quoted informants, Colombo would bring out the bullhorn and shout down the printed word.

It was compulsive, almost theatrical.

And it revealed more than he intended.

A man confident in his innocence does not need a parade to announce it.

A man confident in his integrity does not need to brand every investigation a conspiracy.

A man confident in truth does not need to call the truth “fake.”

Colombo’s protestations were not defenses—they were warnings.

The louder he insisted reality was lying, the more obvious it became that he was.

A Blueprint for the Future

Colombo died long before the modern age of political theatre, but his tactics live on—mutated, amplified, and broadcast through the most powerful microphones on earth.

We now inhabit a time where public figures—again, without naming names—use Colombo’s exact script:

- Deny wrongdoing at every turn.

- Claim victimhood when challenged.

- Demonize investigators and institutions.

- Label all negative reporting as fabrication.

- Cast themselves as martyrs of a corrupt system.

- Flip truth and fiction until both lose meaning.

In Colombo’s day, a lie had to be repeated in front of a crowd to echo.

Today, a lie can circle the globe before breakfast.

A government that normalizes this pattern—where leaders call facts “fake” and treat law enforcement as political enemies—creates a dangerous precedent. It blurs the line between legitimate criticism and deliberate dismantling of reality itself.

And Colombo would have thrived in such a world.

When the Lie Becomes the Man

Colombo’s tragedy is that he believed his own denials. He built a mythology he thought could shield him—not only from the press, not only from law enforcement, but from the Mafia code itself.

He thought legitimacy could be manufactured through volume.

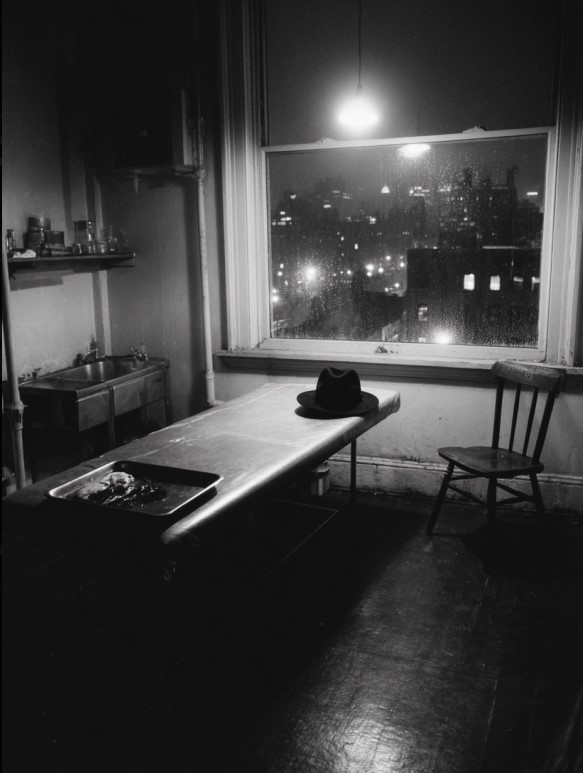

But in the underworld, visibility is death.

Old bosses whispered threats in back rooms; Colombo shouted innocence into microphones.

Old bosses hid in the dark; Colombo ran toward the light.

And on June 28, 1971, at his second Unity Day rally, the illusion shattered.

A gunman stepped forward, raised a pistol, and fired into Colombo’s head at point-blank range.

He lived—but he was already gone.

The man who screamed loudest that he was innocent died in the most guilty way possible:

shot in public at a rally he created to prove he wasn’t a criminal.

The irony was almost Shakespearean.

The Lesson We Still Haven’t Learned

Colombo’s fall is more than Mafia history.

It is a case study in the peril of denial politics—the belief that truth is optional, that reality can be bullied, that facts buckle if you shout hard enough.

And, decades later, we see echoes of the same strategy in powerful figures who insist that every criticism is a plot, every investigation a witch hunt, every fact a fabrication—so long as it inconveniences them.

Joe Colombo tried to bend truth the way he bent bookies and union men.

He learned—violently—that truth has a longer memory than any rally.

Today’s leaders who treat reality the same way should take note.

Because Colombo proved one thing with absolute clarity:

When a man spends all his breath claiming something isn’t true, it is almost always the only thing worth listening to.