They say you live by the gun, you die by it. But Louis “Little New York” Campagna didn’t get that ending. No back-alley shootout. No revenge hit from a rival crew. No final standoff in a smoky dive. When death came for Campagna, it didn’t wear a badge or carry a switchblade. It came disguised as a sunlit day, a fishing rod, and 30 pounds of thrashing grouper.

May 30, 1955—Memorial Day. The streets of Chicago were quiet, but Louis wasn’t there. He was far from the windy alleys that once echoed with the sounds of tommy guns and sirens. He was on a boat off the coast of Miami, chasing fish instead of blood. Maybe he thought he was finally out. Retired. Clean. Untouchable.

He was wrong.

Louis Campagna had spent his life neck-deep in the shadows, a made man who rose from Brooklyn backstreets to the bulletproof inner circle of Al Capone himself. In the Outfit, his name meant something. It meant fear. Loyalty. Violence. He was the kind of guy who didn’t blink when it was time to put someone down—and he had put plenty down.

Born in 1900, most likely in Brooklyn, Campagna came up hard and fast. The stories say he ran with the Five Points Gang—the same proving ground as Capone. He was built for the life: silent, brutal, smart enough to survive but cold enough to kill. Whether he followed Capone to Chicago or just found his own way west, by 1919, Campagna had already been convicted of bank robbery. Prison couldn’t hold him for long. By the time he was out in late 1924, his real work had only just begun.

They called him a bodyguard, but that was just window dressing. Louis Campagna was a button man—one of Capone’s most trusted killers. When the Aiello brothers tried to take out the big boss, it was Campagna who helped turn the city into a war zone. He handled hits with the precision of a surgeon and the cold detachment of a machine. When Capone needed the South Side cleaned up, Campagna showed up with steel in his veins and a loaded revolver in his coat.

He was there the day the Outfit nearly turned a police station into a slaughterhouse. Joe Aiello had been arrested, and Capone wanted him dead before he could say a word. Six taxis pulled up to the precinct—each one packed with gunmen. Campagna stepped out calm, steady, his piece tucked in his jacket, eyes sharp. But fate blinked before he could pull the trigger. A cop spotted his gun. He was arrested on the spot and tossed in a cell next to Aiello. He leaned in close and whispered like the Reaper himself: “You’re dead, friend. You won’t get to the end of the street still walking.”

He was right. Aiello eventually caught twenty-three bullets to the face.

Through the ‘30s and ‘40s, Campagna climbed higher in the Outfit. He wasn’t just a hitter anymore. He was upper management in the empire of sin. He made money off gambling dens, muscled into labor unions, and helped engineer the mob’s move into Hollywood—shaking down the studios through their control of the stagehands’ union. He didn’t smile much. He didn’t talk unless he had to. But when he did, people listened. Or they disappeared.

One time, when a front man named Willie Bioff got cold feet and talked about walking away from the scam, Campagna made the message crystal clear: “Anybody who resigns, resigns feet first.”

Eventually, Bioff flipped. The feds came down like thunder. Campagna got convicted in a massive racketeering case, sentenced to time in Atlanta Federal Pen. But even behind bars, he wasn’t just another inmate. He got himself transferred to Leavenworth, thanks to political pressure greased by mob hands. Tony Accardo himself came to visit. Campagna was still in the game—he was just playing it from a different seat.

But here’s where the story stops sounding like a gangster movie and starts reading like a grim joke from the gods.

Campagna is out. He’s older, softer around the edges, but still sharp. Still dangerous. Maybe he thought the worst was behind him. That the ghosts had stopped following. That he’d finally earned a little peace.

So he went fishing.

He went fishing on his lawyer’s boat off the coast of Miami. The sky was blue. The water calm. The bait cast. It was supposed to be just another quiet day with a rod in hand and salt on the breeze.

Then he hooked a big one. A 30-pound grouper. The line bent. The reel spun. Campagna leaned in, muscles straining.

And then—he dropped.

Just like that.

Heart attack. Instant. No warning. No drama. Just silence. One second he’s fighting a fish, the next his heart taps out like it had finally had enough. No last words. No enemies in sight. Just the Florida sun and the sound of waves.

The fish got away.

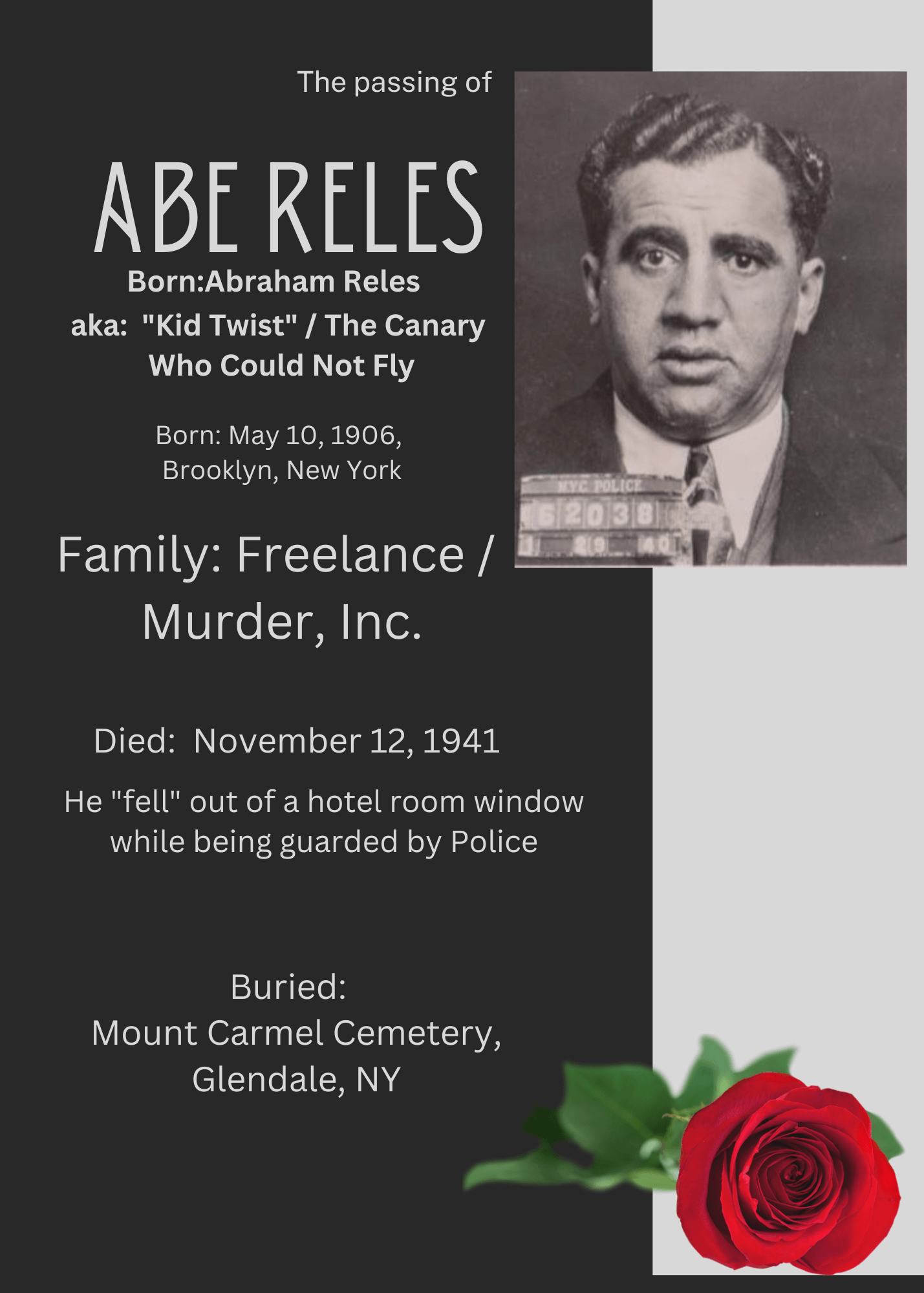

The Church refused him a Requiem Mass. Said he was too dirty for that kind of blessing. But the Outfit didn’t care. Berwyn, Illinois lit up with a funeral that looked more like a state affair. Black cars lined the block. Men in dark suits stood in silence, stone-faced, hats in hand. Campagna was buried at Mount Carmel Cemetery—mob holy ground. Capone was already there. So was Frank Nitti. That day, they made room for another king.

No blood. No bullets. Just a boat, a fish, and a final exhale.

There’s something almost funny about it—if you’ve got the kind of humor that runs with killers. Campagna spent his life putting people in the ground, and in the end, he got outplayed by a fish. A guy who made others “sleep with the fishes” ends up dying for one. That’s not just ironic—that’s cosmic. That’s fate with a twisted grin.

He thought he was out. He thought he’d ride the waves, catch some dinner, maybe toast the sunset with a glass of bourbon.

But the street never forgets. And neither does fate.

Louis Campagna died the one way no one expected—peacefully, almost laughably, undone not by revenge or betrayal, but by nature itself. For a man who lived with a finger on the trigger and a target on his back, it was the quiet that finally got him.

And in the final tally of his life, it wasn’t the feds, the rats, or the rivals who won.

It was the fish.

By C.F. Marciano – The Godfather of Gritty Tales