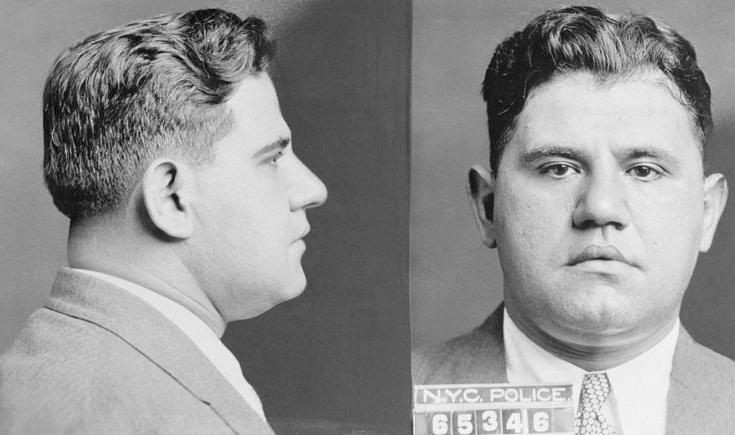

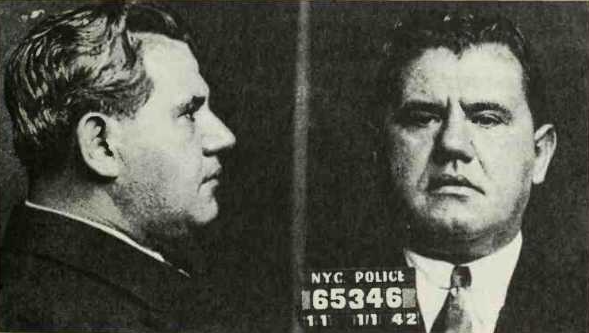

In the twisted depths of New York’s criminal underworld, where blood mixed with seawater and ambition reeked of dead fish and desperation, one name commanded fear, respect, and power: Joseph “Socks” Lanza. A brute with ham-sized fists and a mind sharper than any fishmonger’s blade, Lanza was more than just a mob enforcer — he was the iron-fisted king of the Fulton Fish Market, a shadowy emperor reigning over ice-crusted docks, floundering union men, and millions in dirty dollars.

Born in Palermo, Sicily in 1904, Lanza was forged in the fire of immigrant struggle and hardened on the cold concrete streets of Lower Manhattan. By the time he was a teenager, he had traded schoolbooks for seafood, slinging crates of fish under the rotting awnings of the Fulton Fish Market. But Lanza wasn’t just hauling halibut — he was watching, learning, and waiting.

He clawed his way into the United Seafood Workers Union, Local 359, and by 1923, “Socks” was more than a name — it was a brand. A whisper of it in the Market could make grown men tremble. He earned it not just for the thunderous blows he dealt out to those who crossed him, but for his signature tactic of punching enemies into unconsciousness, socking them hard and fast before they could blink. His rise in the union wasn’t democratic — it was violent, strategic, and soaked in blood.

Murder at 105 South Street

On the morning of May 19, 1926, the stench of blood mixed with fish guts outside the union headquarters. The bullet-riddled corpse of William Mack, an Irish labor agitator with delusions of stealing the market from the Mafia, lay crumpled in a pool of gore. Mack wasn’t innocent — his rap sheet included assault and burglary — but his true crime was challenging Lanza’s grip on the docks.

Sergeant John Armstrong followed a crimson trail up to the second floor of M. Slavin and Sons at 105 South Street. There, behind a splattered bar, he found the final clues — blood, a bullet hole, and silence. Lanza and three of his associates were charged, but in classic underworld fashion, the charges slipped off like fish scales under a blade. The Mafia had spoken — the docks belonged to Socks.

Blood, Ice, and a $20 Million Empire

By the 1930s, Lanza had done more than just defend his turf — he had built a criminal empire. Through the union, he squeezed wholesalers with cold efficiency, threatening delays in loading and unloading perishable goods. He knew the game: fish rots fast, and time is money. If a wholesaler didn’t pay up, their catch sat and spoiled — a $20 million racket carved out of fear, timing, and intimidation.

But Lanza wasn’t just muscle. He was a tactician. He embedded spies throughout the docks, kept tabs on everyone — from union guys to federal agents. His word was gospel. If Lanza said a crate moved, it moved. If he said a man disappeared, he vanished. The Genovese crime family loved him for it. He turned the fish market into a criminal goldmine, a fortress of flesh and ice under their control.

A Gangster Turns Patriot

In a plot twist no Hollywood screenwriter could conjure, World War II turned this underworld villain into a wartime asset. German U-boats prowled the Atlantic, and the U.S. Navy grew paranoid about enemy sabotage along the vulnerable waterfront.

Enter Operation Underworld — the Navy’s secret, desperate alliance with the Mafia. They needed informants. They needed protection. They needed control. So, they made a deal with the devil.

Lanza, with his stranglehold on the docks and his eyes and ears everywhere, was recruited by the Office of Naval Intelligence. In exchange for leniency, he helped root out Nazi sympathizers, track submarine activity, and ensure the uninterrupted flow of wartime cargo through the New York harbors. The man who had once been public enemy number one became an unlikely guardian of American interests.

And he played the part well.

Behind the scenes, Lanza’s men patrolled the docks more ruthlessly than any sailor. Suspected saboteurs disappeared. Suspicious crates were “accidentally” dumped. The Navy got what it wanted — a secure waterfront. And Lanza? He got power, prestige, and a taste of untouchability.

From Savior to Prisoner

But mob life is never simple. In 1938, Lanza was convicted of labor racketeering — a small price to pay for the fortune he’d amassed. He was later nailed again for extortion and sentenced to 7½ to 10 years in Sing Sing. But like any seasoned mobster, he bided his time. When he walked free in 1950, he returned to his frozen throne as if nothing had changed.

Not even a 1957 arrest for violating parole could shake him. The fish still moved when Lanza said so. The union still bowed to his voice. And the Genovese family still knew his worth.

For nearly two decades, he ruled the docks with the quiet, menacing presence of a storm cloud ready to strike. He didn’t need to scream. A glare, a word, a gesture — that was enough. He had become more than a gangster; he was an institution.

Death of a Dockyard King

Joseph “Socks” Lanza died on October 11, 1968, taking his secrets with him to a grave likely as cold as the fish he once moved by the ton. His death marked the end of an era when New York’s markets weren’t just about commerce — they were about control, fear, and blood.

He left behind no memoirs, no apologies, no regrets. Just stories — whispered in alleyways and taverns, echoed in courtrooms and headlines. Tales of a man who ruled an empire of ice with fire in his veins and fists that spoke louder than bullets.

He wasn’t a fishmonger.

He was a king.

A bloody, ruthless, unforgettable king of the docks. And his shadow still lingers in the mist that rises from the East River — where fish once rotted, and men once vanished, beneath the reign of Socks Lanza.

Crafted by C.F. Marciano – The Don of the Written Word.