In the shadows of the American Mafia’s grand mythos lies a darker truth — one drenched in blood, greed, and a chilling disregard for human life. There’s a romanticized notion whispered among street-corner mob watchers and casual observers: “The Mafia doesn’t harm civilians.” That tidy bit of folklore is dead wrong.

From the twisted mind of Anthony “Gaspipe” Casso — who ordered hits on innocent people, including one in a case of mistaken identity — to the cold-blooded murder of an NYPD officer who had the gall to marry the ex-wife of a Colombo boss, civilians have always been fair game when it served a purpose. But even among these brutal tales, nothing quite compares to the cold, calculated, and utterly senseless terror unleashed by one man: Gerardo “Jerry” Catena.

Catena, a consigliere for the powerful Genovese crime family and a man the FBI considered one of the top criminal minds of his generation, launched a savage war not against a rival crew, not against turncoats or stool pigeons — but against an American supermarket chain.

His weapon of choice?

Detergent.

The Blood Price of Rejection

It was the early 1960s. The Catena brothers — Jerry and Gene — had taken control of a company that manufactured household cleaning products. They had one goal: to muscle their way onto the shelves of the A&P supermarket empire. The product in question was an all-purpose cleaner called Poly Clean, made by the North American Chemical Company, owned by a man named Nathan Sobol.

According to Louis DiVita’s memoir “A Wiser Guy,” Sobol, struggling to expand his sales, was introduced to the Catena brothers through a mutual connection. Jerry and Gene took him in — but “help” from the Mafia never comes without strings. They forced Sobol to hire Best Sales Co., a distribution outfit run by Gene Catena, to push the product into retail giants.

The plan seemed airtight. Catena had muscle in all the right places. Irving Kaplan, head of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters union, and Joe “Peck” Pecora of the Teamsters, both loyal to Catena, applied pressure. Promises were made. Deals whispered.

But when A&P tested the product, they refused to stock it. The detergent was “inferior,” they said.

That’s when the fires started.

Mafia Fire and Fury

The rejection sparked a rampage that turned suburban grocery aisles into crime scenes. Six A&P stores were firebombed. Two store managers were gunned down. Others were beaten. The A&P losses? An estimated $60 million — and several lives.

In one chilling instance, a manager named John Mossner noticed two men casing his Brooklyn store in late 1964. They tried to torch it. A few weeks later, someone slashed his tire. As he crouched to fix it, a bullet tore through his body. He died in the street — another casualty in a war no one understood.

One of the killers was believed to be Joseph Maselli, an enforcer for Nicholas “Cockeyed Nick” Ratenni, a Westchester capo working under Catena. Maselli, already infamous for the torture-murder of an elderly widow, allegedly led the arson team that razed stores to the ground. For A&P, it was like being stalked by a phantom — fire and death came from nowhere, without explanation.

And A&P never saw it coming.

The Silent War Against the Civilian World

What makes the Catena-A&P war so disturbing is not just the violence — it’s the motivation. This wasn’t about territory, revenge, or family honor. It was about shelf space. It was about money, plain and brutal. And when denied what he wanted, Jerry Catena did what few Mafia bosses had dared to do so openly: he turned a commercial rejection into a blood vendetta.

For all the folklore surrounding “codes” and “rules” of Mafia behavior, Catena’s war makes a mockery of it. These weren’t made men or rat-finks catching bullets. These were everyday people who just wanted to go to work, stock produce, and cash out customers.

And they paid with their lives.

The Quiet Rise of a Quiet Killer

So who was this man capable of such ruthless escalation?

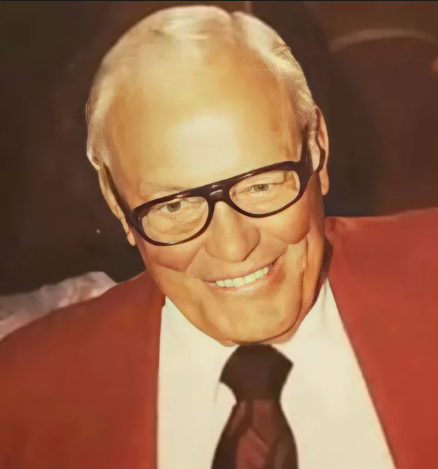

Born in Newark, New Jersey, on January 8, 1902, Gerardo Catena came up as a laborer and house painter before aligning himself with Abner “Longie” Zwillman — a major Jewish mob figure. He eventually partnered with Zwillman in a tobacco business and brushed shoulders with mob royalty: Joe Adonis, Lucky Luciano, Frank Costello.

By 1959, the FBI had him marked. That year, Catena was named to the Genovese ruling panel, one of the highest honors in the underworld. According to FBI files obtained by the Friends of Ours blog, Catena was already a powerhouse in labor unions, jukebox and vending machine companies, and — increasingly — in “legitimate” businesses.

A 1970 New Jersey crime commission pegged his fortune at over $10 million, and by 1986, Fortune Magazine called him the fourth-richest mobster in America. One associate, Anthony “Little Pussy” Russo, put it more bluntly: “Catena had more f—ing money than God.”

He didn’t look like a killer. Living in an upscale brick home in South Orange with his wife and five kids, he projected the image of a successful businessman. But behind the suburban façade lay a calculating mind — one that saw murder as marketing, arson as negotiation.

The Aftermath

By the 1970s, federal authorities had begun to unravel the connections between organized crime and the food industry. Joe Demma and Tom Renner’s investigative series “Underworld Involved in Food Industry” blew the lid off a national racket that infiltrated everything from supermarkets to shipping.

And at the center of that storm was Jerry Catena.

Eventually, the heat forced Catena into the shadows. He stepped down from his consigliere post, though few believed he had truly retired. His empire lived on in silence, in ghost companies and secret deals. By the time the public caught a glimpse of the truth, the blood had long dried and the paper trail had vanished.

Catena died in 2000 at the age of 98 — quietly, in his home, surrounded by luxury. He outlived most of his enemies, outmaneuvered countless investigations, and left behind a legacy soaked in secrets.

But for those who believe the Mafia once operated under some code of civility, the story of Jerry Catena and the A&P is a sobering reminder:

When the mob wants something — even shelf space — no one is safe.

Written by: C.F. Marciano