CARMINE PERSICO’S SELF-DEFENSE PROVIDED LAUGHS BUT NO LEGAL ADVANTAGE FOR HIM OR OTHER DEFENDANTS

The Commission trial continued through November and into December of 1986. The eight men on trial included New York’s top Mafia bosses and a few of their key underlings. The Manhattan courtroom was always standing room only. Arriving early in order to get a seat was worth the effort – this was the best show in town.

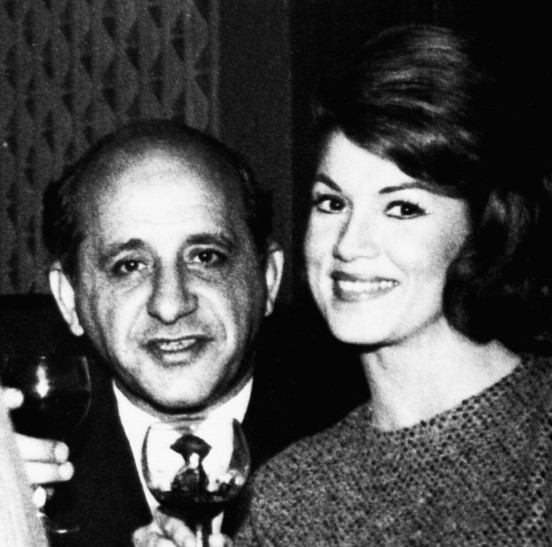

Defendant Carmine Persico, boss of the Colombo crime family, kept one thing in mind as he represented himself. It would take only one juror not to believe the prosecution’s case – one juror could give all eight defendants their freedom.

Persico had to play to that “one.” He believed his Oscar-worthy performance would be the difference between life and life behind bars.

POINT FOR PERSICO

Government witness Angelo Lonardo lamented that he was innocent of the drug charges of which he had been convicted in Cleveland. He explained that he was found guilty because of lies told by two of his underlings.

Persico pounced – in a subtle way – in full view of the jury. “You said you were innocent of that?” Persico asked.

“I am still innocent,” the 75-year-old answered.

“You found another way to get out of jail, is that right?” Persico asked in a curious way.

“To cooperate with the government, yes,” Lonardo answered without hesitation.

“You decided to cooperate, and that is how you are going to get out of jail?” Persico asked. “By doing what somebody did to you – testify?”

“That’s right,” he responded.

Persico smiled and sat down. Defense attorney Anthony Cardinale continued to question Lonardo. His attack was more direct and critical. Cardinale stated, to the jury’s benefit, that Lonardo had lied under oath – more than once – at previous trials. “Sir, perjury is no stranger to you, Angelo Lonardo, is it?”

“Right now,” Lonardo answered, “I’m telling the truth.”

Cardinale knew he had successfully chipped at Lonardo’s credibility. He continued as he asked, “You felt that you were going to die if you were left to stay in jail?”

“Yes,” Lonardo said.

Cardinale pressed further, asking if Lonardo would “testify against your own brother?”

Lonardo gave it a quick thought before answering. “I believe I would, yes.”

IT’S HARD BEING A MAFIA DON

In another taped conversation played for the jury, Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno complained to Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo about a lack of appreciation and respect among the rank-and-file mobsters.

“I know you’ll retire, I know you’ll retire,” Corallo sympathized.

“Listen, Tony,” Salerno said, “If it wasn’t for me, there wouldn’t be no Mob left. I made all the guys. And everybody’s a good guy. This guy don’t realize that? I worked myself. Jeez, how could a man be like that, huh?”

Salerno told Corallo how one of his underlings disrespected him by directly calling him “Fat To

“No, I know the way he talks,” Corallo agreed. Corallo’s solution? “Shoot him. Get rid of them, shoot them, kill them. It’s disgusting.”

He finished by stating, “Here’s to your health.”

‘WENT ON A STICK-UP’

A key witness was Joseph Cantalupo. He was a former Colombo crime family member who identified Persico as the head of the family. Persico had his cross-examination questions ready.

When asked how he knew Persico, Cantalupo explained that he had met him at a Brooklyn realty company in the 1960s. The realty company, he had explained earlier, was a front for illegal activities for the Colombo family.

“And I came there to speak to Joe Colombo?” Persico asked.

“Yes,” Cantalupo said.

“Do you know what I spoke to him about?” Persico asked.

“No,” Cantalupo said.

“Describe for these people my relationship to you,” Persico said.

“Our relationship was only to say hello, shake hands, goodbye, nothing formal,” Cantalupo said.

Persico asked him if they ever “went on a stick-up” together or did “anything illegal” together. Cantalupo had a one-word answer: “No.”

“So, everything that you spoke here in this courtroom about me was knowledge you picked up from other people?” Persico asked.

“Correct,” Cantalupo acknowledged.

Persico contended that Cantalupo, as a paid informant, had used law enforcement agencies to get even with people. It was brought to light that while Cantalupo was a paid informant, he continued to commit robberies and other crimes.

‘YOU WERE MY FAMILY‘

Persico next questioned Fred DeChristopher, one of the most damaging witnesses against him. The two men were related by marriage. DeChristopher was married to Persico’s cousin. DeChristopher acknowledged that while he had allowed Persico to use his Long Island home as a hideout, he was secretly working with a federal agent to get a $50,000 reward.

“You helped me when I came to your house?” Persico asked him with pure sarcasm.

“I did,” DeChristopher said.

Laughter filled the courtroom. That bothered DeChristopher. He asked in a huff, “Wouldn’t you like to see me down the sewer altogether?”

“I don’t think the judge would permit me to answer that question,” Persico answered. The courtroom again filled with laughter.

“I know, I know what your answer would be,” DeChristopher snapped.

“I wish I could tell you,” Persico responded as a smile played across his face. More laughter in the courtroom.

Persico faced DeChristopher. “You were my family.”

DeChristopher barked, “Are you finished?”

“No, I’m not finished,” Persico replied. “I got a lot more to go.”

To emphasize the character of the witness, DeChristopher was asked if he had secretly informed on his wife’s brother – wasn’t he just recently married to her?

“That’s true, that’s true,” he responded. “I was just Joe Citizen calling the FBI with information, yes, sir.”

Shortly after Persico’s arrest in 1985, DeChristopher left home without telling his new wife. He never returned. He did, however, buy a nice home with the $50,000 reward money.

NO DIRECT EVIDENCE?

Wearing a sharp charcoal gray suit, Persico presented his 90-minute summation. “At the beginning of the case, I told you I’m not a lawyer, and I guess you found that was true,” Persico said with a smile.

As he leaned casually on the lectern in front of the jury box, he compared the trial to a “bus tour through tinsel town.” “They had no direct evidence,” he asserted.

“They want to win – they’ll do anything to win,” he said, pointing to the prosecutors. He mocked the prosecution for presenting pictures of a farm his family owned in upstate New York. He ridiculed them for the seemingly endless display of enlarged surveillance photographs they had presented. The charts of the Mafia that the prosecution had provided? Persico thought they were ridiculous.

“They brought in pictures of half of New York State,” Persico remarked, laughing. The jury also laughed.

“Without Fred DeChristopher, Carmine Persico wouldn’t be in this case, wouldn’t be in this courtroom,” Persico contended, referring to a key prosecution witness against him.

He said there was no evidence against him; he wasn’t even on any of the tape recordings. He spoke directly to the jury as he asserted that he had stayed away from all criminal activity. It was his “reputation” that made him a target of a government witch hunt.

“Ladies and gentlemen, I can’t say I never did anything wrong, because you know I was in jail,” he said. But how could he possibly be sent back to prison when there was no evidence against him?

“Our faith,” he concluded as he looked at each of the jury members, “is in the jury.”

In his summation, Cardinale argued that the Commission did not operate a “club” to extort payoffs from concrete companies. “It is a ‘club’ of contractors, not of Commission members. The Commission had nothing to do with the concrete payments.”

He contested the claim by the prosecution that Salerno was the Genovese crime family boss. The tapes of Salerno, he said, did not contain “any threats or any pressure.”

“That, ladies and gentlemen, is not extortion,” he emphasized. He stressed that the concrete companies had “gladly paid” to gain an “advantage in the industry.”

Attorney Dawson contended that the prosecution had presented “guesses, speculations and assumptions” but no solid evidence.

“This case falls at the slightest touch,” Dawson claimed. The taped conversations the jury had listened to? Why, they were just “internal politics and bickering about members belonging to families.”

CASE GOES TO THE JURY

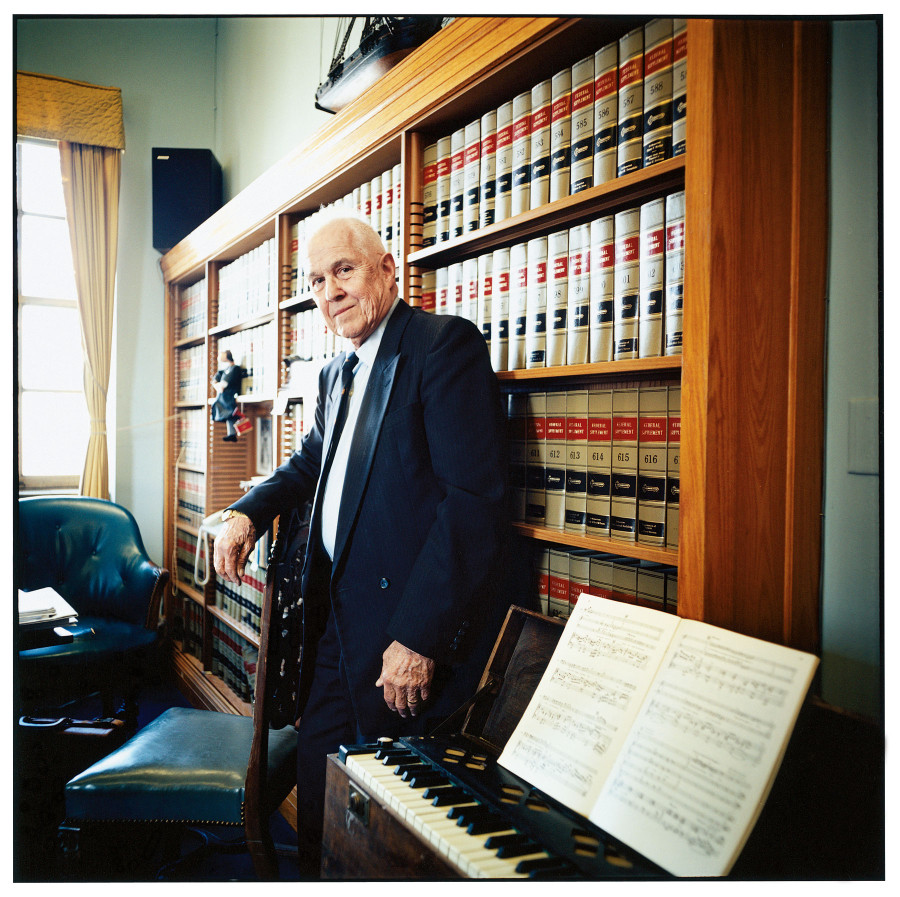

With closing arguments completed on Friday, November 14, 1986, Judge Owen spoke to the jury. He spent close to three hours as he explained that the racketeering charges included conspiracy and related charges. He also made it clear that simply being a member of the Mafia was not sufficient reason for a conviction.

The jury deliberated over the weekend. On Monday the 17th, Persico received some bad news when the ruling from the federal appeals court in his other trial came in. Persico, his son Alphonse, and six others were found guilty of being leaders of the Colombo family. For that alone, Persico received a 39-year sentence.

The jury’s verdict came down on Wednesday, November 19, 1986. After 85 witnesses and 150 tape recordings, jurors delivered a crippling blow to the defendants, finding all eight guilty of racketeering, conspiracy and operating a Commission that ruled the Mafia throughout the United States.

Persico’s mission to convince one juror to reject the prosecution’s case proved unsuccessful.

Regarding the three Mafia bosses, the jury found Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, Carmine “Junior” Persico and Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo guilty of all 22 counts.

“We’ve been steamrolled,” Cardinale responded.

Sentencing was set for January 13, 1987. Each man was facing a minimum of 40 years in prison.

SENTENCES HANDED DOWN

The crowded courtroom murmured in shock as Judge Richard Owen doled out the sentences to the eight defendants. He explained that he was not only sentencing the men, but “overall crime.”

- Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno. The judge stated that Salerno had “essentially spent a lifetime terrorizing the community for your financial advantage.” Sentence: 100 years.

- Carmine “Junior” Persico. For his role as an “upper member” of the Mafia echelon “that lives, succeeds on murder and violence,” Owen sentenced him to 100 years.

- Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo was sentenced to 100 years.

- Gennaro “Jerry Lang” Langella was sentenced to 100 years.

- Salvatore Santoro was next for sentencing. Facing the judge, Santoro said, “You’re in the driver’s seat, your honor.” Judge Owen stated he was just doing his job. Santoro responded with full sarcasm, “And you’re doing a good job” before adding, “Give me my 100 years and we’ll get it over with.” That’s exactly what he got.

- Christopher “Christie Tick” Furnari Sr. was sentenced to 100 years.

- Ralph “Little Ralphie” Scopo was sentenced to 100 years.

- Anthony “Bruno” Indelicato was sentenced to 40 years for the murders of Carmine Galante and his two bodyguards.

Judge Owen, who described the defendants as ruthless racketeers, explained that they would be eligible for parole after 10 years under federal law. But he recommended that parole be denied for all of them.

“This case was prejudiced from the first day,” Persico complained. He contended they were found guilty because of “this Mafia mania that was flying around.”

The 10-week Commission trial – Mafia mania or not – was the first of many crushing blows against the Mafia and its vise-like hold on unions across the country.

A well-known quote states, “A man who is his own lawyer has a fool for his client.” Was Carmine Persico a fool for representing himself? Who knows, but it sure was an interesting “bus trip through tinsel town.”