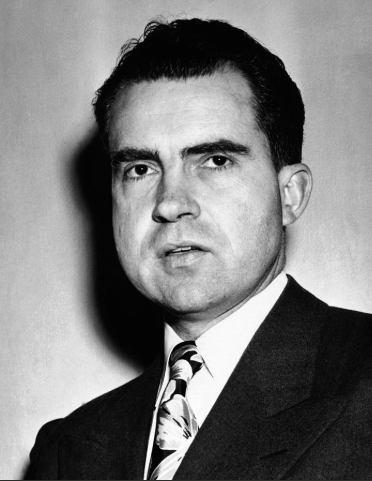

Richard Nixon did not go to prison. He was never indicted. He was never formally charged under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act. And yet, in the darkest irony of American legal history, RICO’s first great takedown was a sitting President of the United States.

The law was written for gangsters. It was designed to break the backs of men who ruled from smoke-filled rooms, who insulated themselves with layers of lieutenants and plausible deniability. It was meant for the Mafia—men like Carlo Gambino, Vito Genovese, and the shadow empires documented in Five Families. But in 1974, the law reached past Little Italy and Union halls and wrapped its fingers around the Oval Office.

And it all began with a signature.

A Law for the Mob

On October 15, 1970, President Richard Nixon sat in the White House and signed the Organized Crime Control Act into law. Buried inside it was Title IX: the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act—RICO.

The moment was ceremonial, but for Robert Blakey, the Georgetown law professor who architected RICO, it was deeply personal. He had spent years crisscrossing the country, pitching lawmakers on a radical idea: stop chasing individual crimes and start prosecuting criminal enterprises. Blakey understood the Mafia the way prosecutors before him never fully had. The bosses didn’t pull triggers. They gave nods. They didn’t steal. They skimmed. They didn’t order murders directly. They let the structure do it for them.

This insight mirrors what Selwyn Raab later detailed in Five Families: the American Mafia survived not because of brute violence alone, but because of organizational discipline, silence, and legal insulation. RICO was designed to puncture that insulation. At the signing, Nixon reportedly turned to Attorney General John Mitchell, handed him the pen, and said: “Go get the crooks.”

Blakey remembered the moment vividly. What Nixon didn’t realize was that, in signing RICO, he had just handed history a loaded gun—and aimed it at himself.

The Clause Nobody Noticed

RICO is remembered for its sweeping conspiracy provisions, its asset forfeiture powers, and its ability to charge bosses for crimes they never personally committed. But RICO’s most devastating weapon against Nixon wasn’t aimed at organized crime at all.

It was a quiet, technical provision expanding Congress’s power to grant immunity to witnesses testifying before Senate and House committees.

At the time, no one cared. It wasn’t controversial. It wasn’t debated. It didn’t make headlines. It was legislative boilerplate—useful, dull, and easily ignored.

That clause would later crack the Nixon presidency wide open.

Watergate and the Enterprise

When burglars were arrested inside the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex in June 1972, the White House went into damage-control mode. What followed was not a single crime, but a coordinated, hierarchical cover-up—a pattern of obstruction, hush money, false statements, and misuse of federal agencies. This is where the Mafia analogy becomes unavoidable.

As documented in Five Families, mob bosses survived because crimes were compartmentalized. Soldiers took the risks. Capos managed logistics. Bosses stayed insulated. Nixon’s White House operated the same way. Orders were implied. Loyalty was expected. Silence was rewarded. Deniability was currency.

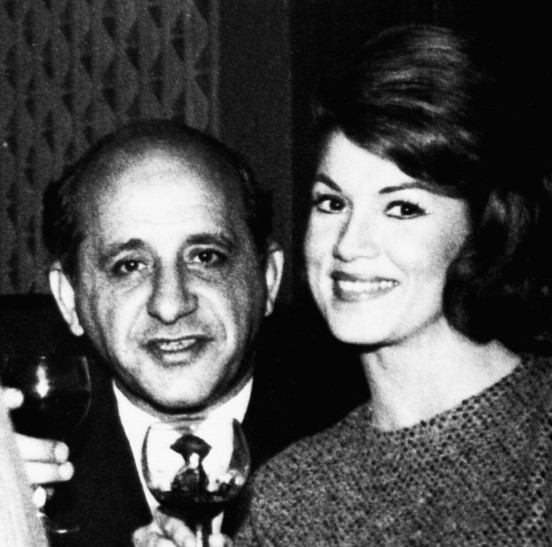

John Dean, the young White House Counsel, found himself trapped in this structure. He was not the boss. He was not a foot soldier. He was a mid-level operator staring down a conspiracy larger than himself.

And then Congress came calling.

Immunity and the Fall

In 1973, the Senate Watergate Committee began televised hearings that riveted the nation. Thanks to the expanded immunity provisions embedded in the Organized Crime Control Act, Congress could now offer witnesses protections broad enough to compel testimony.

John Dean took the deal.

With limited immunity, Dean testified that President Nixon had knowledge of the cover-up, had discussed payments of hush money, and had participated in efforts to obstruct justice. The testimony was devastating. It wasn’t rumor. It wasn’t speculation. It was insider confirmation. Dean would later be convicted of obstruction of justice himself. His immunity was not total. Like many mob turncoats before him, he paid a price. But his testimony did what decades of journalism and opposition politics could not: it made Nixon’s continued presidency legally impossible.

Facing near-certain impeachment and removal, Nixon resigned on August 8, 1974.

No indictment was needed. The enterprise had collapsed.

RICO’s First Irony

Years later, Bob Blakey reflected on the moment Nixon signed RICO into law. “When Nixon signed the bill,” Blakey recalled, “he handed the document to John Mitchell, the attorney general, and said, ‘Go get the crooks.’ And who were the most prominent people brought down by the act—Richard Nixon and John N. Mitchell.”

Mitchell, the nation’s top law enforcement officer, would later be convicted of obstruction of justice, conspiracy, and perjury. The enforcer became the defendant.

This was RICO’s first great irony: a law designed to destroy criminal syndicates exposed a political one instead.

The Mob, the State, and the Pattern

RICO didn’t send Nixon to prison, but it did something arguably more profound. It established a principle that no hierarchy—criminal or political—was immune from collapse once insiders began to talk. The Mafia learned this lesson painfully in the 1980s when RICO prosecutions dismantled the Five Families of New York. Bosses who once seemed untouchable were suddenly defendants in courtrooms, undone by their own structures.

Nixon’s White House fell the same way.

An enterprise.

A pattern of illegal acts.

An expectation of silence.

A single insider who breaks.The parallels are chilling—and intentional.

Legacy of a Law That Bites Back

Today, RICO is used against drug cartels, corrupt corporations, street gangs, terrorist networks, and political corruption rings. Its reach is vast, controversial, and often misunderstood.

But its first real victory wasn’t against a mob boss in a silk suit. It was against a president in a dark blue one. Richard Nixon didn’t see it coming. Few did. But history is rarely kind to men who build systems of loyalty and secrecy and assume they control every moving part. RICO proved that the structure itself could be the crime.

And sometimes, the law meant to hunt monsters ends up finding one in the mirror.