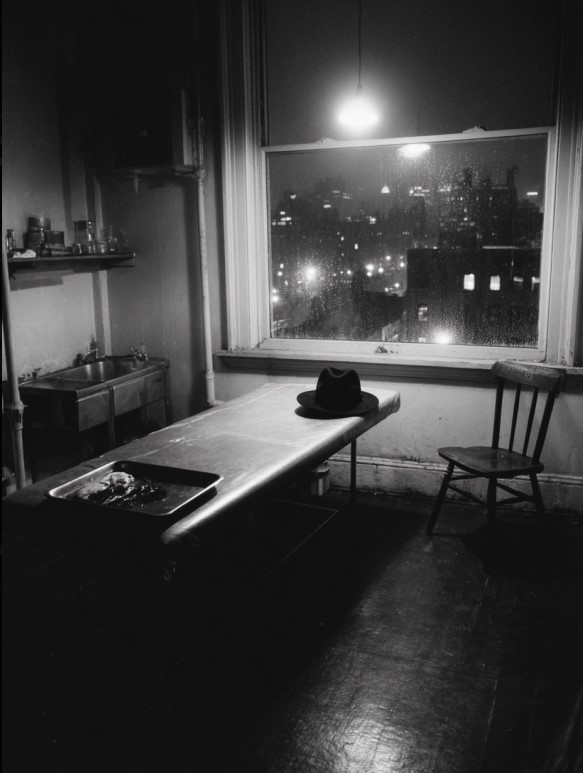

Professional wrestling has always existed in the shadows, a business built on illusion, ritualized violence, and silence. It sold fantasy as truth and demanded loyalty in return. Long before it became a billion-dollar global entertainment empire, wrestling lived in smoke-filled arenas, grimy armories, and half-lit civic centers where cash changed hands and questions were dangerous. It was here, in that gray space between legitimacy and theater, that organized crime found professional wrestling not as a prize to conquer, but as a system already fluent in its language.

Unlike boxing, wrestling never needed the Mafia to fix outcomes. The promoters had already done that. What the mob understood, and what wrestling promoters learned early, was that control doesn’t always come from ownership. Sometimes it comes from proximity. Sometimes it comes from standing just close enough to collect.

In the middle decades of the twentieth century, professional wrestling was fragmented into territorial monopolies. Each city belonged to a promoter. Borders were respected, betrayals were punished, and business was conducted quietly. This system resembled organized crime so closely that it is difficult to believe the similarities were accidental. Regional bosses enforced non-compete agreements. Talent was loaned, traded, or frozen out. Those who broke the rules were blacklisted, beaten, or erased from the industry. Wrestling did not need the Mafia to teach it how to operate as a racket. It arrived there on its own.

The Mafia’s interest in wrestling was never about the ring. It was about everything surrounding it. Wrestling required buildings, and buildings required labor. Labor, in many major American cities, meant unions. And unions, particularly in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Boston, were deeply entangled with organized crime. Stagehands, security, ticketing staff, transportation, concessions—these were the pressure points. If a promoter wanted to run weekly shows without disruption, he needed cooperation. Cooperation often came at a price, one rarely written down.

Madison Square Garden stood as the cathedral of professional wrestling, the place where champions were crowned and legends were made. Capitol Wrestling Corporation, the ancestor of the modern WWE, ran its business there for decades. There is no credible evidence that the Mafia owned Capitol Wrestling or booked its matches. What there is, instead, is context. New York’s labor environment during that era was famously mob-influenced. No large-scale entertainment operation in the city functioned without navigating a web of union power, political influence, and informal arrangements that guaranteed “labor peace.” Wrestling was not special in this regard. It was simply discreet.

That discretion mattered. Kayfabe, the unspoken code that demanded absolute secrecy about wrestling’s scripted nature, extended far beyond the ring. It covered money, power, and relationships. Promoters didn’t advertise who they paid or why. Wrestlers didn’t ask. Silence was not just tradition; it was survival. Breaking it meant exile from an industry with a long memory and few second chances.

The promoters themselves were rarely Mafia members. Most were something more useful: connected businessmen who understood how to operate in mob-adjacent ecosystems. Some had familial ties. Others had long-standing business relationships. Many simply paid what needed to be paid and kept their mouths shut. Wrestling’s reliance on cash made it easy to skim, easy to launder, and easy to deny. In that sense, wrestling was less infiltrated than accommodated.

Organized crime prefers industries that don’t invite scrutiny. Wrestling, for decades, was treated as carnival entertainment, not a serious business. Athletic commissions often ignored it. Regulators dismissed it. That indifference created opportunity. The Mafia did not need to muscle into wrestling because wrestling already lived outside the spotlight.

The contrast with boxing is revealing. Boxing offered gambling, uncertainty, and fighters who could be pressured into losing. Wrestling offered none of that. The outcome was known before the bell rang. That made mob involvement in match results unnecessary and potentially dangerous. Exposing manipulation in wrestling would have exposed the entire illusion, collapsing the business itself. Organized crime has always been pragmatic. It avoided killing the goose that laid the golden eggs.

Wrestlers, for the most part, understood the rules. They knew which cities were sensitive and which promoters demanded discretion. They knew when to keep their heads down and when to move on. The culture of silence was enforced not through overt threats, but through economic reality. There were only so many places to work. Reputation mattered. Talking too much meant not working at all.

As wrestling moved onto television in the 1950s and 1960s, the dynamics shifted but the underlying patterns remained. Local television stations were often tied to political machines and union labor. Wrestling needed airtime to survive. In some markets, connections eased the path. In others, they closed doors. Promoters learned quickly who controlled access and how to stay in favor. Again, this was not unique to wrestling. Organized crime had long understood media influence. Wrestling simply adapted.

The territorial system endured until one man broke it. When Vince McMahon Jr. took control of the World Wrestling Federation in the early 1980s, he dismantled the old order. He centralized power, went national, and turned wrestling into a corporate entertainment product. In doing so, he eliminated the fragmentation that organized crime thrives on. National television contracts replaced local gate receipts. Corporate venues replaced union-heavy armories. Wrestling became too visible, too centralized, and too profitable to tolerate the inefficiencies of mob influence.

Ironically, wrestling’s escape from organized crime did not come through indictments or investigations. It came through capitalism. The mob was not forced out; it was priced out.

There are no RICO cases that expose the Mafia running wrestling promotions. No wiretaps of mob bosses booking champions. No confessions from made men admitting they controlled the squared circle. What exists instead is a constellation of patterns: shared environments, shared structures, shared silences. Wrestling lived comfortably in the same shadows as organized crime because it was built to survive there.

Kayfabe was the mob’s greatest ally. Both depended on myth, loyalty, and the fear of exposure. Both understood that the truth was less important than the story people believed. When the lights went down and the crowds left, the ring was just wood and steel. The real power existed elsewhere, in contracts, labor agreements, and quiet understandings that never appeared on paper.

The Mafia did not need to own professional wrestling. It only needed to remain close enough to remind everyone how the world really worked.