In the underworld, obedience is currency. You follow orders, you stay alive. You refuse, you disappear. That logic has been whispered in back rooms, barked in social clubs, and sealed with blood oaths for more than a century. Hitmen pulled triggers. Capos skimmed money. Soldiers enforced silence. When the indictments came down, the defense was almost always the same:

I didn’t make the rules. I just followed them.

It’s a convenient lie. A comforting one. And one that American law—especially the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO)—has spent decades tearing to pieces.

Because in the eyes of the law, obedience does not equal innocence. Orders do not erase intent. And following commands does not absolve criminal responsibility.

The Myth of Moral Outsourcing

The phrase “I was just following orders” carries a dark historical echo. It was infamously invoked by Nazi officials at the Nuremberg Trials, where the world rejected the idea that obedience could excuse atrocity. American courts carried that lesson forward. Criminal liability does not vanish simply because someone else gave the command.

In organized crime, this defense became especially common as the Mafia professionalized its hierarchy. Bosses insulated themselves. Orders flowed downward. Violence and fraud flowed outward. When arrests followed, soldiers and capos claimed they were replaceable cogs—interchangeable parts in a machine they didn’t control.

Prosecutors disagreed.

Enter RICO: The End of the Excuse

Passed in 1970, RICO changed everything. Before RICO, prosecutors had to charge mobsters for individual crimes: one murder, one loan-shark operation, one extortion scheme. That fragmentation allowed defendants to hide behind hierarchy.

RICO smashed that structure.

Under RICO, participation in a criminal enterprise itself is the crime. You don’t need to be the boss. You don’t need to give orders. If you knowingly furthered the enterprise—even by “just following orders”—you are legally responsible for the pattern of racketeering activity.

In other words: You pulled the lever, you’re in the machine.

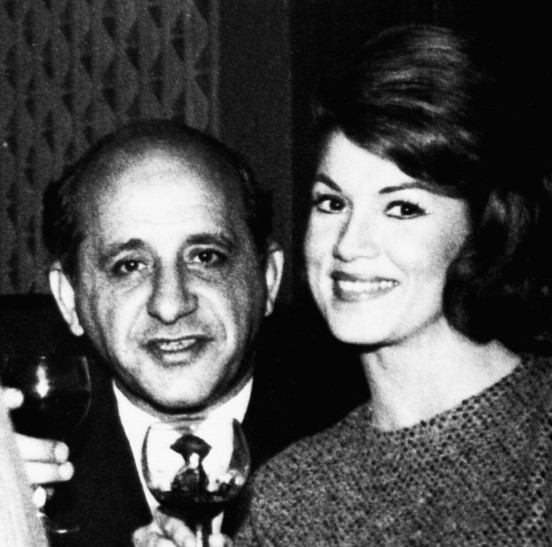

Example 1: Albert DeMeo and the Myth of the Loyal Soldier

Albert DeMeo, son of Roy DeMeo—one of the most notorious killers in Gambino history—wasn’t the architect of Murder, Inc.–style carnage. He was a participant. He drove cars. He helped dispose of bodies. He followed his father’s instructions.

At trial, loyalty didn’t matter. Bloodlines didn’t matter. The jury saw a man who knowingly assisted a criminal enterprise built on murder. DeMeo was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment without parole.

The verdict sent a message through the underworld: lineage and obedience are not shields.

Example 2: Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano—Before He Flipped

Before becoming the government’s star witness against John Gotti, Sammy Gravano was the model underboss. He enforced orders with ruthless efficiency, later admitting to involvement in 19 murders.

Gravano’s original posture was obedience. He claimed Gotti gave the orders. He followed them. That argument carried no weight. It wasn’t until he cooperated—fully confessing and accepting responsibility—that he avoided a life sentence.

Even then, the law never pretended he was innocent. His reduced sentence was transactional, not moral. The courts were clear: following orders did not absolve him; cooperation merely mitigated punishment.

Example 3: The Commission Case—Everyone Was Guilty

The 1986 Commission Trial may be the single clearest rejection of the “just following orders” defense in Mafia history. Prosecutors used RICO to indict the heads of New York’s Five Families, proving that the Mafia functioned as a national criminal enterprise.

Lower-level defendants attempted to distance themselves. They weren’t decision-makers. They were messengers. Enforcers. Facilitators.

The jury didn’t care.

Under RICO, knowingly participating in the enterprise—regardless of rank—was enough. The verdicts shattered the illusion that only bosses bore responsibility. Orders didn’t flow in one direction; guilt didn’t either.

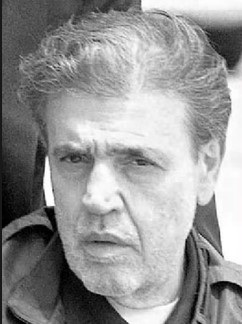

Example 4: Anthony “Gaspipe” Casso’s Crew

Lucchese underboss Anthony “Gaspipe” Casso issued orders that turned his faction into a paranoid killing machine. His soldiers carried them out with chilling precision, often murdering on suspicion alone.

At trial, several of those soldiers argued they feared retaliation if they refused. They were following orders to survive.

The courts acknowledged the fear—and rejected the defense.

Fear may explain behavior, but it does not excuse it. The law draws a hard line between coercion and choice. None of Casso’s men were forced at gunpoint. They chose loyalty over legality, and they paid for it with decades behind bars.

Example 5: Michael “Mikey Scars” DiLeonardo

DiLeonardo, a Gambino capo, later testified against John Gotti Jr. He admitted to multiple acts of violence and racketeering, all carried out under orders from above.

His testimony revealed a critical truth: Mafia obedience is voluntary. You can walk away. Many don’t—but the option exists. That distinction destroys the “no choice” argument.

DiLeonardo wasn’t punished because he followed orders. He was punished because he knowingly chose to follow criminal ones.

Why the Defense Always Fails

Courts consistently reject the “just following orders” defense for three reasons:

- Knowledge – Defendants understood the criminal nature of their actions.

- Volition – They were not physically forced to comply.

- Benefit – They profited from obedience through money, power, or protection.

RICO collapses hierarchy into shared responsibility. It treats the enterprise like a living organism—and every participant as a functioning organ. If the body commits crimes, the organs don’t get a pass.

The Cold Truth of the Underworld

The Mafia sells obedience as survival. The law sees it as conspiracy.

Every oath, every order, every silent nod in a back room binds the participant tighter to the enterprise. When indictments come, excuses sound hollow against wiretaps, surveillance photos, and testimony from men who finally decided loyalty wasn’t worth dying in prison for.

“I was just following orders” might work in a war movie. It doesn’t work in federal court.

And RICO made sure it never would again.

References

- United States v. Turkette, 452 U.S. 576 (1981)

- United States v. Salerno et al. (The Commission Case), 868 F.2d 524 (2d Cir. 1989)

- Blakey, G. Robert & Gettings, Brian. Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO): Basic Concepts. U.S. Department of Justice

- Maas, Peter. Underboss: Sammy the Bull Gravano’s Story of Life in the Mafia

- Capeci, Jerry. The Complete Idiot’s Guide to the Mafia

- United States v. Casso, 9 F.3d 101 (2d Cir. 1993)

- FBI Records: Organized Crime and RICO Prosecutions

- Senate Report No. 91-617 (1970), Organized Crime Control Act

Sidebar: From Nuremberg to RICO — Why “Just Following Orders” Died in Court

The excuse didn’t start with the Mafia.

Long before wiseguys used it in federal courtrooms, “I was just following orders” was tested on a global stage—at Nuremberg.

After World War II, Nazi officials stood trial for crimes so vast they defied comprehension. Their defense was chillingly uniform. They weren’t architects of genocide, they said. They were bureaucrats. Soldiers. Functionaries. They followed commands issued from above. The system demanded obedience. Refusal meant death.

The tribunal rejected that argument outright.

The Nuremberg Trials established a principle that still haunts criminal defendants today: moral and legal responsibility does not dissolve inside a hierarchy. Orders may explain why a crime was committed—but they do not erase who committed it.

American lawmakers took note.

When Congress passed the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) in 1970, it quietly embedded the Nuremberg logic into domestic law. Organized crime, like authoritarian regimes, thrived on compartmentalization. Bosses issued orders. Underlings executed them. Everyone claimed plausible deniability.

RICO was designed to kill that structure.

Under RICO, the question is not who gave the order, but who knowingly participated. If you furthered the goals of a criminal enterprise—by enforcing, collecting, killing, laundering, or intimidating—you were no longer a pawn. You were part of the machine.

Just as Nuremberg rejected the idea that bureaucratic obedience excused crimes against humanity, RICO rejects the idea that criminal obedience excuses racketeering.

The Mafia tried to argue fear. Loyalty. Tradition. Courts answered with evidence: wiretaps, ledgers, bodies, and testimony from insiders who proved that participation was a choice—often a profitable one.

The parallels are uncomfortable, but deliberate.

Both legal frameworks recognize the same truth: systems don’t commit crimes—people do. And hiding behind rank, orders, or culture does not absolve responsibility.

In the end, the courtroom verdict is the same whether the uniform is military gray or tailored pinstripe:

You chose to comply.

You knew what you were doing.

And you are guilty anyway.