A Story of Ambition, Bribery, and Bullets in the Windy City’s Fight for Media Supremacy

Chicago, 1910s. A city choking on ambition, corruption, and smoke. The clatter of printing presses mingled with the crackle of Tommy guns. On these grimy streets, newspaper tycoons didn’t just battle with headlines—they fought with fists, bribes, and bullets. At the center of this blood-inked battlefield was Moses “Moe” Annenberg, a street-smart circulation man who turned newspaper delivery into urban warfare and became a kingmaker in American media.

The Battlefield: A City Divided by Newsprint

In the early 20th century, Chicago was home to a ruthless war over news dominance. Newspapers were not just businesses; they were propaganda machines, political tools, and status symbols. The major players—William Randolph Hearst’s Chicago American and the Chicago Tribune, among others—vied for readers in a city already teetering on chaos.

Circulation numbers were everything. Papers lived or died by how many copies they could sell each morning. And behind the clean-cut headlines were legions of “circulation goons” armed with brass knuckles, blackjacks, and sometimes handguns—ready to intimidate, sabotage, and kill.

It was the golden age of yellow journalism—truth was optional, drama was mandatory.

Moe Annenberg: The Architect of Mayhem

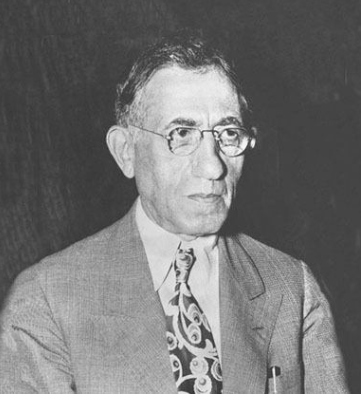

Born in 1877 to German-Jewish immigrants, Moe Annenberg climbed from humble beginnings as a newspaper boy to become the architect of one of the bloodiest distribution networks in American history. Working first for The Milwaukee Journal, Moe made his name in Chicago’s cutthroat newspaper scene by the mid-1910s. He became circulation manager for Hearst’s Chicago operations, and quickly transformed the business into a streetwise empire.

Annenberg was the Don Corleone of the ink wars—recruiting ex-cons, bootleggers, and ex-boxers to strong-arm newsstand operators and intercept rival papers. Newspaper trucks were hijacked. Newsboys were beaten senseless. Entire city blocks were “protected” by hired thugs loyal to Moe.

Moe knew how to play both the boardroom and the back alley.

Chicago’s Circulation Wars: A Bloody Business

The 1910s saw the rise of violent skirmishes between Hearst and Tribune delivery men. In 1910, the so-called “Circulation Wars” escalated when rival newsboys and hired enforcers clashed regularly, resulting in dozens of injuries and several deaths.

According to historian Richard Norton Smith, “The circulation wars in Chicago resembled low-intensity gang warfare, often indistinguishable from the actual mob turf fights that came later.”

By the 1920s, Chicago was awash in gang activity. The lines between newspaper syndicates and organized crime blurred. Al Capone’s outfit and other mob elements were frequently contracted to “help manage” circulation zones. While there is no direct proof that Moe Annenberg colluded with Capone, their spheres certainly overlapped. Both ruled Chicago through fear, control, and the flow of information—one through booze and bullets, the other through newspapers and numbers.

The Rise of a Kingmaker

Annenberg left the Chicago scene in the late 1920s to manage Hearst’s Racing Form and later founded his own news empire with the Daily Racing Form and The Philadelphia Inquirer. He eventually became one of the richest men in America, his name rising even as his past remained shrouded in blood and smoke.

But his aggressive tactics caught up with him. In 1939, Moe Annenberg pleaded guilty to income tax evasion, fined $8 million, and was sentenced to two years in federal prison—one of the largest tax cases in U.S. history at the time. He died shortly after his release.

Still, Moe’s legacy lived on in his son, Walter Annenberg, who would go on to become one of the most influential publishers and philanthropists of the 20th century. The Annenberg Foundation, seeded by Moe’s fortune, became a pillar of education and journalism reform—ironic, considering Moe’s street-fighting roots.

The Lasting ImpactThe newspaper wars of 1910s–1920s Chicago were more than a local rivalry—they set the tone for the modern media machine, where reach and influence mattered more than ethics. The battles weren’t just about selling papers. They were about controlling narratives, shaping public opinion, and enforcing loyalty—by any means necessary.

Today’s media moguls might wield algorithms and ratings, but back then, it was baseball bats and boot money that decided the morning’s headlines.

Written by C.F. Marciano