In the shadowed alleys of early 20th-century America, where the proletarian poor hustled for survival and the criminal elite built empires from narcotics, gambling, and bootleg liquor, there rose a man more feared by the underworld than a squad of armed Treasury men. He was not a gangster. Not a cop. Not even a street-level enforcer.

He was a bureaucrat — which somehow made him more dangerous.

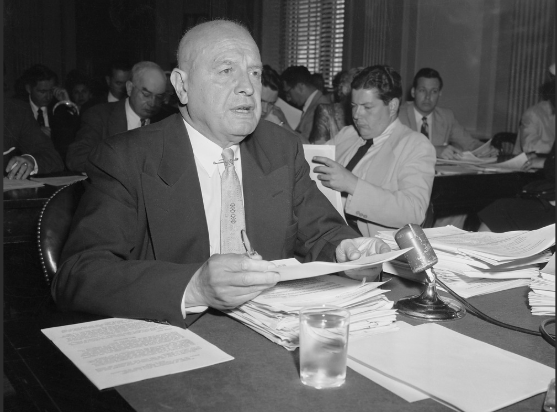

Harry Jacob Anslinger, the first commissioner of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN), didn’t carry a Tommy gun or stalk speakeasies. He didn’t need to. His weapon was power — legislative, political, far-reaching — and he wielded it with an iron grip for more than three decades. Ask anyone in the Mafia’s narcotics rackets during the 1930s through the 1950s. They feared this man.

And they were right to.

The Rise of a Narcotics Czar

When Anslinger took the helm of the newly formed FBN in 1930, the United States was a country already torn by organized crime. Prohibition had transformed bootleggers into millionaires and murderers into businessmen. Narcotics — once a niche commodity trafficked by small-time smugglers — were rapidly becoming a high-profit enterprise for syndicates looking to diversify.

Anslinger walked into this world with a puritanical fury and an almost surgical understanding of its criminal anatomy.

The FBN began small: just 271 agents patrolling an entire nation.

But under Anslinger, they behaved less like civil servants and more like a paramilitary force. He forged alliances with international policing bodies, pushed for strict uniform narcotics laws, and quietly stockpiled opium reserves in federal vaults years before World War II disrupted supply lines. That foresight earned him admiration — and enemies.

He went wherever the drug trade led: racetracks, city ports, international waters, even the medical community. No arena was safe from his reach. When doped racehorses began scandalizing the sports pages, he sent agents after the trainers using heroin, cocaine, and strychnine to rig victories. When smugglers tried to launder narcotics through diplomatic channels, he unspooled entire networks.

He was not creative. He was not compassionate. But he was effective — ruthlessly so.

Marijuana, Morality, and a War of Words

Though heroin and opium were his primary battlegrounds, Anslinger eventually set his sights on marijuana, a drug he would turn into a national villain. While early in his career he showed little interest in cannabis, something changed. By the mid-1930s, he began pushing a sensational narrative — lurid tales of marijuana turning ordinary Americans into murderers, degenerates, and societal threats.

Whether he believed his own propaganda remains debated.

But the results were not.

His campaign helped usher in the Marijuana Tax Act of 1937, a landmark in national drug prohibition and the spiritual father of federal cannabis laws for decades to come. Through magazine articles, congressional testimony, and relentless public messaging, Anslinger cultivated fear. A new frontier in narcotics law enforcement was born.

The Mafia’s Nightmare: Anslinger vs. Charles “Lucky” Luciano

The American Mafia had long relied on bootlegging as its lifeblood. But with the repeal of Prohibition in 1933, their empires needed reinvention. Many found opportunities in heroin — compact, profitable, international, and brutally addictive.

Enter Charles “Lucky” Luciano.

By the time Anslinger fixed his gaze upon him, Luciano had already restructured the American underworld. He built The Commission. He modernized rackets. He established global contacts in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia — regions that produced the very opiates Americans craved.

Luciano wasn’t just a kingpin.

He was the architect of a multinational narcotics pipeline.

Anslinger despised him.

From the 1930s into the postwar era, Anslinger’s FBN aggressively tracked Luciano’s movements. Even after Luciano’s imprisonment and eventual deportation, Anslinger remained convinced he was re-establishing drug operations overseas. His agents gathered intelligence in Italy, France, Cuba, the Balkans — anywhere Luciano’s shadow touched.

Whether Luciano was truly masterminding global heroin networks or merely a convenient political enemy is debated by historians. But to Anslinger, he represented everything the narcotics czar believed he was fighting: corruption, vice, and international criminal enterprise.

The two never met, but their conflict defined an era.

Anslinger’s determination pressured foreign governments, influenced treaties, and at times disrupted trafficking corridors. Luciano’s own myth grew, partly because Anslinger inflated him into a global villain to justify the FBN’s increasing power.

It was a war waged through diplomacy, media, intelligence networks, and public perception — a bureaucrat’s battle with a criminal titan.

And for a time, Anslinger was winning.

A Bureaucratic Empire

By the 1950s, Anslinger had achieved near-total dominance over U.S. narcotics policy. His fingerprints touched every major legislative milestone:

- The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937

- The Boggs Act (1951) imposing harsh mandatory minimums

- The Narcotics Control Act (1956) introducing even stricter penalties, including the death sentence for selling heroin to minors

He expanded the FBN’s international presence, built the first police training academies for narcotics enforcement, and represented the U.S. at the United Nations during formative years of global drug policy. He also became a symbol of harsh justice — quoted as calling addicts “immoral, vicious, social lepers.”

Admired by some. Hated by many.

Feared by all.

Anslinger served until 1962, longer than any narcotics chief before or since. By the time he left, he had crafted a complex, aggressive enforcement infrastructure — one that would eventually morph into the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) in 1973.

The DEA’s Fragile Future — Anslinger’s Shadow Over a Splintering System

Nearly a century after Anslinger’s rise, the federal institutions he helped build face a strange and perilous transformation.

Reports from inside the Justice Department indicate discussions about merging the DEA with the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) — a sweeping reorganization framed as a cost-saving measure. Critics fear the move would dilute specialized narcotics expertise, especially if field divisions are closed or agents reassigned.

At the same time, federal drug prosecutions have plummeted to their lowest levels in decades, a sign that narcotics enforcement is no longer the priority it once was. Complex trafficking cases — the kind Anslinger dedicated his career to — require long-term investigative muscle. And this, analysts warn, is precisely what could be lost in a merged, downsized, or refocused agency.

For the American Mafia — historically intertwined with narcotics smuggling, especially heroin — this institutional weakening is more than bureaucratic trivia. It changes the playing field. It shifts the pressure. It reshapes the federal threat. Anslinger once strangled narcotics pipelines with international treaties and nationwide crackdowns. Today, those same pipelines have evolved, diversified, and migrated into multinational cartels, synthetic drug labs, and encrypted networks.

If Anslinger were alive, he might not recognize the modern narcotics landscape.

But he would recognize the danger of weakening enforcement during a time of escalating complexity.

Legacy of a Relentless Commander

Harry Anslinger remains one of the most polarizing figures in American criminal history. Admirers champion him as the father of federal narcotics control — a visionary who built something from nothing. Critics condemn him as a fear-mongering authoritarian whose policies laid the groundwork for decades of mass incarceration.

Both views hold truth.

But one fact is undeniable:

Anslinger won battles against some of the most powerful criminal forces of his era. He pursued mob networks with unrelenting precision. He outmaneuvered traffickers, diplomats, and political opponents. He created a system — flawed, rigid, often brutal — that still shapes American drug policy today.

And now, as parts of that system face upheaval, restructuring, or reduction, Anslinger’s ghost lingers.

A reminder that institutions built on iron will can crumble when their purpose becomes blurred, neglected, or politically inconvenient.

If the modern underworld has learned anything from the past century, it’s this:

The criminal landscape changes, but the absence of strong, specialized enforcement creates shadows — and the shadows are where the Mafia has always thrived.