It wasn’t the drugs. It wasn’t the guns. It wasn’t even the loan sharking that built the quiet fortunes of the Five Families. It was garbage.

Rotting fish guts. Grease-slicked cardboard. Meatpacking refuse crawling with flies. The kind of stuff no one wants to see, smell, or think about. But for the American Mafia—particularly in New York and North Jersey—trash became an empire of power, control, and silent violence. A billion-dollar black market, built on the backs of broken bones and unmarked graves.

The mob didn’t just infiltrate the garbage industry. They owned it. And God help you if you tried to haul someone else’s trash without kissing the ring.

The Perfect Crime Hiding in Plain Sight

Unlike drugs or arms trafficking, garbage was legit. Or at least it looked that way on paper. Private waste hauling was an unregulated gold mine—steady cash, low risk, and invisible to most. City contracts and commercial clients meant repeat business. And because nobody paid attention to what happened after the dumpsters were emptied, the mob had free rein to operate in the shadows.

The streets of New York were carved up like mafia territory in a war zone. Routes weren’t assigned by business deals—they were claimed through muscle. If you were a restaurant owner in Queens and you wanted to change haulers? You got a visit. Maybe someone flattened your tires. Maybe your grease trap got torched. Or maybe you got dragged into the alley and reminded whose name was on your garbage.

They called it the “property rights” system—a twisted underworld version of capitalism. You didn’t own your customers. The mob did.

Trash Lords: How the Mob Took the City

By the 1970s, the Lucchese, Gambino, and Genovese families had locked down New York City’s private waste industry with an iron grip. It wasn’t about who had the best trucks. It was about who had the toughest enforcers.

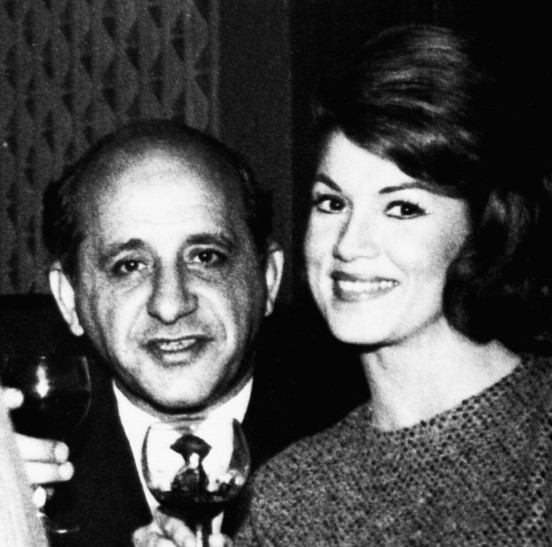

Take James “Jimmy the General” Failla, a top Gambino capo who ran garbage like a Roman general ran provinces. Failla controlled dozens of hauling companies and enforced “discipline” with a network of soldiers who cracked skulls for fun. His meetings weren’t boardroom negotiations—they were shakedowns. Cross him, and your business didn’t just die—it went up in flames.

Mobbed-up carting firms didn’t just scare away competition. They worked in concert, fixing prices, inflating contracts, and threatening clients who even thought about switching haulers. It was a cartel in every sense of the word—but without the jungle, just dumpsters and dark alleyways.

In Brooklyn, one hauler testified that after refusing to pay “tribute,” his trucks were firebombed and his driver’s face was rearranged with a crowbar. Another ended up in a shallow grave outside Staten Island, wrapped in industrial plastic.

And all the while, the city paid its bills, businesses signed their checks, and the stench kept rolling through the streets unnoticed.

Union Muscle and the Invisible Hand

The mob’s control didn’t stop at the trucks. They owned the unions too—most notoriously Teamsters Local 813, which represented sanitation workers in New York. If you were hauling trash, you needed union labor. And if you wanted union labor, you needed to kiss the ring of whichever capo owned the district.

Refuse companies that didn’t play ball found themselves short-staffed, sabotaged, or suddenly under OSHA inspections that somehow always followed a “warning” from a guy with a pinky ring and a crooked smile.

The Association of Trade Waste Removers of Greater New York was another front—a fake trade group that pretended to be a legitimate industry body. In reality, it was a mob-run gatekeeper that collected dues, set fake “market rates,” and punished defectors.

There was no free market. There was no negotiation. There was only the street rule: You haul where we tell you, or we haul you into the East River.

Operation Wasteland: Going Undercover in Hell

By the early ‘90s, the stink of corruption finally caught the attention of Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau, and with it, the NYPD and FBI launched Operation Wasteland—a deep-cover sting that would pull back the plastic tarp on decades of mafia garbage rule.

Two undercover detectives, posing as the owners of a new hauling company called Fieldtech, entered the game like fresh meat tossed into a den of wolves. What they found was worse than anyone imagined.

Recorded conversations detailed how routes were divvied up over espresso and blood threats. One wiretap caught a Lucchese enforcer laughing about “hitting a guy with his own trash can” because he tried to undercut rates. Fieldtech had to pretend to pay bribes, follow rigged pricing, and smile while mobsters fondled their ledgers like they were fondling hostages.

When the indictments came down in 1995, it was a bloodletting. 23 arrests. Dozens of companies exposed. Key players from the Gambino, Lucchese, and Genovese families were charged with racketeering, enterprise corruption, and extortion.

But the cleanup didn’t come easy. The mob doesn’t vanish just because you spray it with bleach.

Reform? Or Rebrand?

After the takedown, New York created the Trade Waste Commission—later renamed the Business Integrity Commission (BIC)—to license and monitor private haulers. Background checks, financial disclosures, and route regulations were meant to scrub the city clean.

But you don’t wash blood out of the concrete that easily.

Even in the 2000s and 2010s, mob influence slithered back in. The Colombo family, thought to be weakened after internal wars and arrests, quietly tried to muscle back into the Brooklyn hauling scene. In 2013, the New York Times uncovered renewed intimidation tactics—fake invoices, locked dumpsters, and “collection fees” that smelled a lot like protection money.

Whistleblowers described how mobbed-up companies rebranded under relatives’ names or dummy corporations. The names changed. The rules didn’t.

Why Garbage?

Why did the mob love garbage?

Because it was boring. Because it was necessary. And because it was unseen. The perfect camouflage.

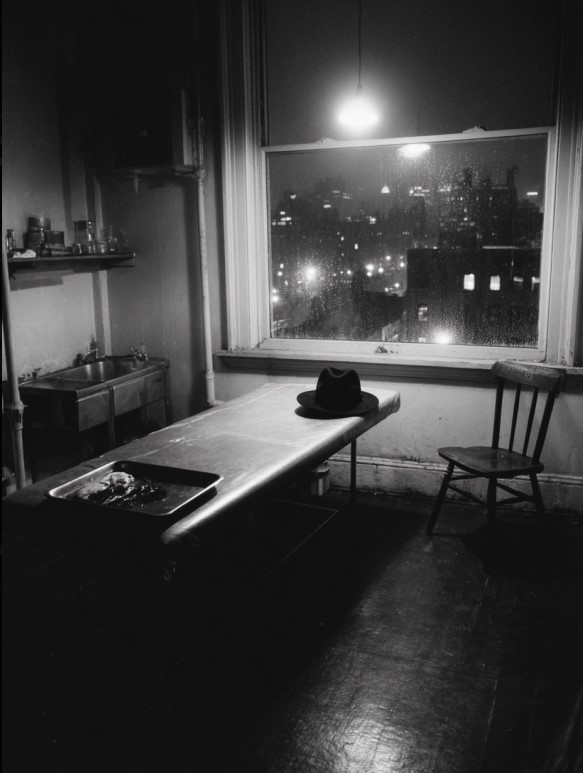

The trucks ran every day, rain or shine. No one questioned the invoices. No one watched the alleys at 4 a.m. It was a business of shadows—a world where grease covered more than just the floors, it covered the ledgers and the lips of those who dared to speak up.

Garbage is also territorial. Routes are mapped like drug corners—once you’re in, you’re in. Once you’re out, you stay out. And the people who tried to change that? They didn’t get warnings. They got funerals.

The Mob’s Trash Legacy

Today, the mafia’s grip on New York’s garbage business has been loosened, but not broken. The muscle has softened, but the blueprint remains.

Waste management is still a billion-dollar industry. It still runs at night, in the dark, behind closed doors and backdoor deals. And while the names on the trucks are cleaner, the history underneath is soaked in blood and bile.

The Five Families didn’t just take out the trash. They became the trash. And they made sure everyone else paid for the pickup.

References:

- Cowan, Rick, and Douglas Century. Takedown: The Fall of the Last Mafia Empire. Penguin, 2005.

- Raab, Selwyn. Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires. Thomas Dunne Books, 2005.

- The President’s Commission on Organized Crime, 1986.

- “Operation Wasteland: Prosecutors Target the Garbage Mob.” The New York Times, May 1995.

- “Mob Still Lurking in New York’s Trash Business,” The New York Times, Sept. 2013.

NYC Business Integrity Commission – www.nyc.gov