The Golden Gate Inn was the kind of place where shadows outnumbered the candles. The tablecloths were spotless, the waiters silent, and the back booths—those were reserved for men who didn’t have to ask. On a good night in the 1950s, the air smelled like garlic, cigar smoke, and fear.

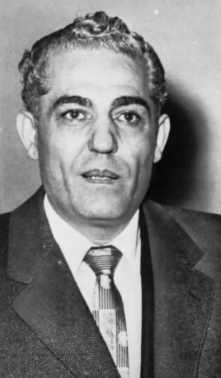

If you lingered too long near the corner table, you might have caught a glimpse of him: Carmine Lombardozzi, the Brooklyn shark in a silk tie, sipping wine while balancing an empire. He wasn’t the kind of gangster who made headlines with gunfire. He made them with numbers.

They called him “The Doctor,” and his clinic was crime.

The Gentleman from Red Hook

Born in Brooklyn’s Red Hook neighborhood in 1913, Lombardozzi came from the hard cobblestone streets that built the American Mafia. Like so many sons of immigrants, he learned early that opportunity came in two forms—one legal, one not.

By his twenties, Carmine had graduated from petty hustles to the higher echelons of organized crime. He had the brains of a banker, the patience of a spider, and the loyalty of a man who knew too much.

Where other mobsters ruled with fear, Lombardozzi ruled with quiet control. He wasn’t a trigger man or a street enforcer; he was a financier, an architect of underworld economics. By the mid-1940s, he had embedded himself deep within the machinery of the Gambino crime family, becoming a trusted adviser to Carlo Gambino himself.

The streets called him “The Doctor” because he could fix anything—books, debts, or people.

The Golden Gate Inn: A Front with Fine Dining

While the average Brooklynite knew the Golden Gate Inn as a classy Italian restaurant—dimly lit, with an orchestra trio playing old Neapolitan songs—those in the know understood it was more than that.

It was Lombardozzi’s headquarters in disguise. Deals were whispered there between forkfuls of linguine. The booths were padded not for comfort but for privacy. The maître d’ knew who to seat and when to look away.

Carmine’s table—always in the back corner—became legendary. Men in expensive suits would come and go, their faces pale and their pockets lighter. The staff said he tipped well but never smiled. If he laughed, it was soft—like the rustle of a hundred-dollar bill.

Rumor has it that envelopes of cash changed hands under the table, that debts were settled over dessert, and that one man who dared to question Carmine’s “terms” never made it home. The next morning, the tablecloth was washed, the floor was swept, and dinner service resumed as if nothing had happened.

In the world of organized crime, the Golden Gate Inn wasn’t just a restaurant—it was a temple of quiet power, a place where the mob’s new financial class came to dine and dictate.

The Business of Crime

Lombardozzi’s empire wasn’t built on blood—it was built on balance sheets. His specialties were loan sharking, gambling, extortion, and money laundering, and he did it with surgical precision.

He used the Brooklyn waterfront as a cash pipeline, funneling money through union rackets and longshoremen’s wages. The docks became both his ATM and his vault. But where most gangsters flaunted their wealth, Carmine kept his understated—sharp suits, a modest home, and a mind that worked like a calculator.

He was a gangster who spoke the language of accountants, and that made him indispensable. When the government cracked down on mob violence in the 1950s, Carmine simply moved his business from the street corner to the office desk.

He was the quiet accountant of an empire built on noise.

A Calculated Silence

By the mid-1950s, federal investigators had marked Carmine Lombardozzi as one of the key money men of organized crime. He was subpoenaed to appear before the Kefauver Committee and later before Senate hearings on organized crime, but if they expected cooperation, they didn’t know Carmine.

He invoked the Fifth Amendment more than 90 times—each refusal a silent smirk in the face of federal power.

To the mob, this was the highest form of loyalty. To the press, it was infuriating. When asked afterward how he made his living, Lombardozzi said simply, “I’m good with numbers.”

Behind those numbers, though, were broken kneecaps, offshore accounts, and the invisible machinery of mob finance.

The Taxman Cometh

In 1965, Carmine’s luck nearly ran out. The New York Times reported that Lombardozzi had been indicted for income tax evasion, accused of hiding more than $130,000 in illegal earnings. Federal prosecutors hoped to “Capone” him—nail him on paperwork where bullets had failed

The case dragged on for years, and though he faced prison time, Lombardozzi remained unshaken. He hired the best lawyers, smiled for the cameras, and served his sentences like a gentleman—quietly, without complaint, and without naming a single name.

When he walked out of prison, older but untouched, the mob took notice. In a world where loyalty was dying, Carmine Lombardozzi was one of the last men still playing the old game by the old rules.

The Final Course

By the late 1970s, the Golden Gate Inn was fading—its white tablecloths yellowed by cigarette smoke, its clientele shifting from mobsters to locals seeking nostalgia. Lombardozzi himself had aged into something like a legend.

He no longer needed to sit at the corner table; his empire was already written in invisible ink across the ledgers of Brooklyn businesses and union accounts. Still, old-timers swore they saw him there from time to time—alone, glass of red wine in hand, a ghost revisiting his altar.

He died in 1992 at age 79, leaving behind a quiet fortune and an even quieter reputation. The obituaries called him a “businessman.” The FBI files called him a “criminal mastermind.” But to those who knew him best, he was the man who could make crime look respectable.

Some say the Golden Gate Inn’s corner booth is still cursed. The waiters feel a chill there, and the candles never seem to burn quite right. Maybe it’s just a draft. Or maybe it’s Carmine, running numbers in the afterlife, still making sure the books balance.

Mob Menu: Dining with Ghosts

If you ever find yourself in Brooklyn, order the veal marsala and a glass of red. Sit near the back. Feel the hush in the air and the weight of history pressing against the linen.

The Golden Gate Inn is gone now, but the stories aren’t. Somewhere between the scent of garlic and the whisper of an old Sinatra tune, you might just hear Carmine Lombardozzi’s voice saying what he always did:

“It’s nothing personal. It’s just business.” And if you’re wise, you won’t ask for the corner table.