When The Godfather arrived in bookstores in 1969—and then detonated across movie screens in 1972—it didn’t feel like fiction. It felt like a confession. Audiences sensed it immediately: this wasn’t just a gangster story dreamed up in isolation. It carried the weight of lived experience, whispered secrets, and brutal authenticity. Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola never claimed The Godfather was a documentary, but they didn’t need to. The mafia recognized itself in the mirror, and so did the public.

What made The Godfather dangerous—then and now—is not simply that it depicted organized crime, but that it did so with intimacy. It showed violence inside the home, not just in alleyways. It revealed how power speaks softly and kills loudly. And it borrowed liberally from real-world mafia lore—sometimes directly, sometimes through stories that had circulated for years in New York’s underworld.

The line between fact and fiction was never meant to be clean.

Violence Comes Home: Connie Corleone and a Familiar Horror

One of the most disturbing storylines in The Godfather isn’t a hit or a mob war—it’s Connie Corleone being beaten by her husband, Carlo Rizzi. The scenes are ugly, prolonged, and intentionally uncomfortable. This wasn’t cinematic excess. It was realism.

Stories of mob daughters brutalized by their husbands were not rare in mid-century Mafia circles. Power did not equal protection—especially for women. In some real-life cases, high-ranking mobsters tolerated abuse of their daughters as “family business,” until it crossed a line that embarrassed the family or threatened its authority.

There are long-circulating claims that a real mafia boss’s daughter—often associated in retellings with figures like Paul Castellano of the Gambino family—endured domestic abuse at the hands of her husband, only for the marriage to end mysteriously and the husband to later vanish from public life. Whether every detail of those stories holds up under scrutiny is almost beside the point. What matters is that The Godfather reflected a truth the Mafia itself recognized: violence against women existed behind the velvet curtains of “family honor.”

Carlo’s fate in the film—executed quietly after Connie’s abuse is finally addressed—fits perfectly into that moral universe. The Mafia didn’t punish cruelty; it punished disobedience and disrespect. Connie wasn’t avenged because she was a victim. Carlo was killed because he betrayed the family.

That distinction is chilling—and accurate.

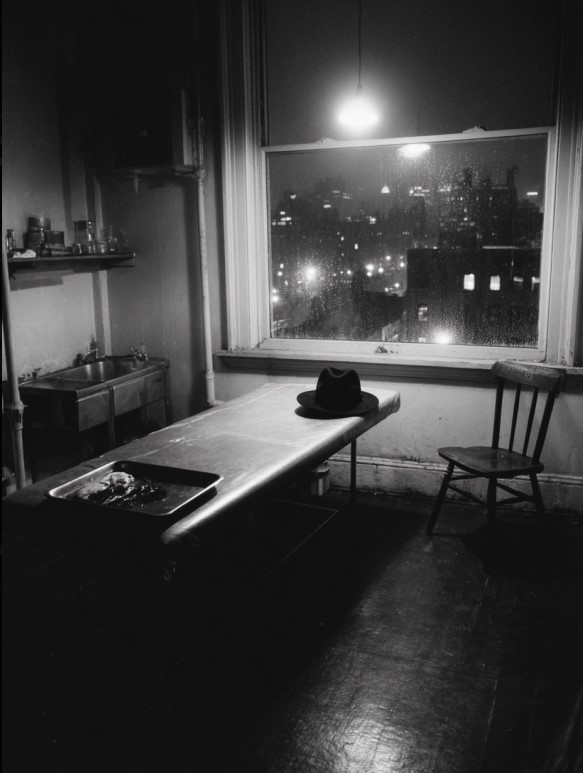

Bars, Back Rooms, and Strangulation Myths

The mafia doesn’t always kill with guns blazing. Sometimes it kills with hands, ropes, or whatever is close enough. The Godfather understood that violence is often intimate, improvised, and humiliating.

One infamous scene involves Luca Brasi being strangled in a bar—an unglamorous, desperate death. Over the years, this moment has been linked by fans and crime historians to real-world stories involving members of the Gallo crew in New York. Larry Gallo, brother of the more famous Joe “Crazy Joe” Gallo, survived at least one brutal strangulation attempt in a barroom altercation in the early 1960s. He lived—but barely.

In real life, Joe Gallo himself would later be murdered publicly at Umberto’s Clam House, riddled with bullets rather than choked to death. But the idea of barroom strangulation—the rawness of it, the message it sends—was very real in mafia culture. Death wasn’t always about efficiency. Sometimes it was about proximity. About sending a signal that no place, not even a crowded bar, was safe.

The Godfather absorbed that atmosphere rather than copying a single event. It captured the way mafia violence often felt personal, angry, and up close.

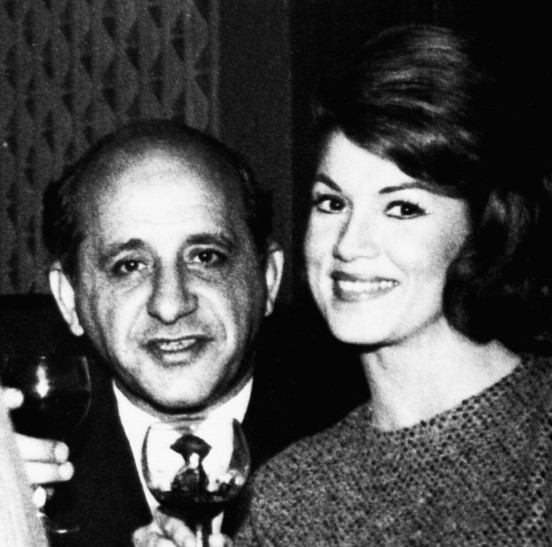

Borrowing a Voice: Frank Costello and the Sound of Power

Perhaps the most famous real-world borrowing in The Godfather isn’t visual at all—it’s auditory.

Marlon Brando’s Don Vito Corleone doesn’t shout. He rasps. He murmurs. His voice sounds damaged, restrained, and weary, as if power itself has eroded his throat. That voice wasn’t invented in a vacuum.

Brando reportedly studied recordings and footage of Frank Costello, the real-life “Prime Minister of the Underworld.” Costello survived a 1957 assassination attempt that left him with a gunshot wound to the head and lasting vocal damage. After that, his speech was halting and gravelly—quiet but commanding.

Costello was also known for something Don Corleone embodied perfectly: restraint. He preferred negotiation over bloodshed, influence over chaos. He didn’t need to yell. People leaned in to hear him speak.

When Brando adopted that voice, he wasn’t just creating a character. He was channeling a type of mafia boss the public had never seen dramatized so accurately. The result was revolutionary. Don Corleone sounded like someone who had survived too much violence to glorify it—yet would still order it without hesitation.

Composite Characters and Stolen DNA

It’s important to understand that The Godfather didn’t lift most of its characters wholesale from real life. Instead, it created composites—fictional figures stitched together from dozens of mobsters, stories, and rumors.

Vito Corleone contains pieces of Frank Costello, Carlo Gambino, and even elements of Lucky Luciano’s old-world logic. Sonny Corleone echoes hot-headed enforcers who couldn’t survive in a business that required patience. Michael Corleone reflects a recurring mafia tragedy: the educated son who believes he can stay clean—and can’t.

Puzo himself admitted he wasn’t deeply embedded in mafia life. What he was embedded in was research, gossip, and pattern recognition. He listened to how these men talked, how they justified themselves, how violence was framed as necessity rather than cruelty.

That’s why The Godfather feels truer than true. It doesn’t rely on facts alone. It relies on psychology.

Why the Mafia Hated—and Loved—The Godfather

Publicly, many real-life mobsters denounced The Godfather. Privately, some adored it. Others recognized themselves in it with discomfort bordering on fear.

The Italian-American Civil Rights League protested the film’s language. Crime families reportedly sent “advisors” to sets. And yet, after its release, mobsters began quoting it. Mimicking it. Living into it.

That’s the final irony: The Godfather didn’t just borrow from the mafia. It fed back into it. The myth reshaped the reality. Younger gangsters modeled themselves after characters who were themselves modeled after older gangsters.

A closed loop of violence, style, and storytelling.

The Truth Beneath the Myth

The Godfather endures because it understood something essential: organized crime isn’t just about crime. It’s about family myths, masculine pride, silence, and selective morality. It’s about what people tell themselves to sleep at night.

By drawing from real mafia happenings—domestic abuse, disappearances, barroom violence, damaged voices of aging bosses—it grounded its operatic drama in something disturbingly human.

That’s why it still unsettles us.

Because somewhere beneath the suits, the weddings, and the iconic lines, The Godfather whispers an uncomfortable truth: the scariest monsters aren’t invented.

They’re remembered.