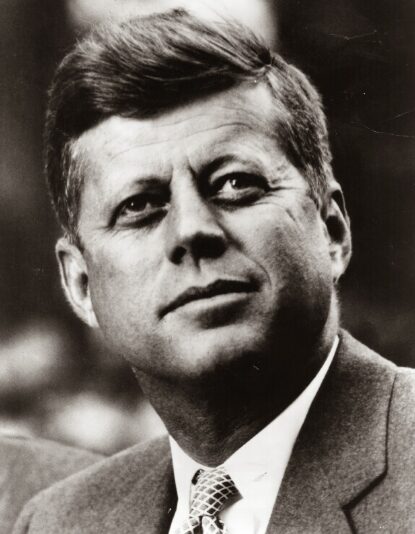

The motorcade rolled through Dealey Plaza on November 22, 1963, beneath a sunlit sky and the cheers of thousands, but behind the polished chrome and smiling faces lay a far darker story. To many in the underworld, John F. Kennedy was not merely a president—he was a traitor to old promises, a snake in the garden of organized crime. And his brother Robert, relentless in his pursuit of justice, had become the embodiment of the Mafia’s nightmare. Theirs was a vendetta that could only end in blood.

The Mafia had once seen Kennedy as a potential ally. Some historians argue that figures like Sam Giancana and other Chicago Outfit bosses quietly supported JFK’s 1960 presidential campaign. Joseph Kennedy, the patriarch, is said to have brokered a deal: deliver votes in key urban centers, and the Kennedy family would protect certain mob interests. But once JFK occupied the Oval Office, the calculus changed. Instead of protection, the Mafia got retribution, and the brunt of that fury came through his brother, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy.

Robert Kennedy became, in the eyes of the underworld, “enemy number one.” He pursued mob figures with an intensity that bordered on personal obsession, targeting not only the big names but also their sprawling networks of racketeering, gambling, and labor corruption. From Jimmy Hoffa to smaller regional bosses, RFK’s Justice Department dismantled empires and humiliated those who had once believed themselves untouchable. For mob leaders, this wasn’t a political campaign—it was a declaration of war.

The loss of Cuba as a playground for profit added fuel to the fire. Before Castro’s revolution, Havana had been the Mafia’s golden playground, a city where casinos flourished under their control. When the revolution toppled the regime, mob leaders like Santo Trafficante Jr. saw years of influence and wealth vanish almost overnight. Kennedy’s tacit alignment with the CIA in plots to overthrow Castro further complicated the equation. The Kennedy administration, in the eyes of the mob, had taken what was theirs, and the brothers’ interference in Cuba was a personal affront as well as a financial threat.

Personal vendettas deepened the anger. Carlos Marcello, the New Orleans crime boss, reportedly resented the Kennedys on a profoundly personal level. House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) records later suggested Marcello had the motive, means, and opportunity to carry out a hit. Allegedly, in prison, he spoke to cellmates about orchestrating Kennedy’s death, a claim echoed in numerous investigative accounts. Trafficante, according to his lawyer Frank Ragano, once lamented that the plot hadn’t targeted Robert instead—a chilling statement of the personal hatred that roiled among the mob hierarchy.

The Mafia did not lack capability. Their networks were vast and disciplined. With deep connections in Chicago, New Orleans, Florida, and beyond, they could coordinate across cities and states, mobilizing personnel and resources in a way few organizations could rival. The very tactics that enforced loyalty in their criminal enterprises—stealth, intimidation, and cold-blooded execution—could be repurposed for a political assassination. And the Mafia had already been working with government agencies like the CIA, whose desperate need to remove Fidel Castro led to clandestine collaborations. Figures such as Johnny Roselli acted as intermediaries, linking high-level mobsters with CIA operatives. These covert ties offered not just opportunity but a form of plausible deniability.

Assassination was no stranger to the mob. Silencing rivals, informants, or traitors was standard practice. The same discipline, patience, and ruthlessness that preserved their criminal empires could also shield a presidential plot from detection. Their networks extended into the legitimate world, through unions, businesses, and political connections, allowing them to operate in shadows that few outsiders could penetrate. The HSCA concluded that organized crime had the people, motive, and means to orchestrate Kennedy’s death.

By November 1963, the perfect storm had formed. Betrayal, vengeance, and desperation collided. The mob felt deceived by the Kennedys’ broken promises and targeted by their relentless legal campaigns. Losses in Cuba had deepened the sting. The CIA’s frustrated and often clandestine operations provided opportunity and leverage. And with seasoned figures like Marcello and Trafficante motivated to act, the underworld’s machinery was poised to strike.

Connections between Lee Harvey Oswald, Jack Ruby, and known mob figures further complicated the narrative. Ruby himself had deep underworld ties, which some conspiracy theorists argue provided cover for a Mafia-directed assassination. According to accounts from Ragano and other investigative authors, Trafficante and Marcello discussed their roles in ways that implied Oswald had been a convenient fall guy, not the primary architect.

After Kennedy’s death, the Mafia’s victory was as hidden as the plotting that produced it. Trafficante allegedly toasted his own deathbed confession, implying the operation could have been directed at Robert instead, revealing the depth of the vendetta. Marcello reportedly spoke to a cellmate about his manipulation of events to frame Oswald. The National Archives acknowledge that by late 1962 and 1963, mob figures had the motive, the opportunity, and the means to take extreme action.

The Mafia’s case against Kennedy reads like a dark narrative of promises, betrayal, and revenge. The Kennedys may have believed they could leverage organized crime for their own ends, but they underestimated the ruthlessness and agility of the very world they had once courted. While no single piece of evidence definitively proves that the Mafia fired the fatal shot, the alignment of motive, opportunity, and capability is undeniable. In the shadows of power and ambition, the Mafia possessed both the hatred and the means to exact vengeance, turning resentment into history-altering action.

The streets, casinos, and backrooms of America in the early 1960s tell a story of power unrestrained, of grudges held for years, of lethal patience. When all factors converged in Dallas, the underworld’s grievances became a deadly calculus—a reminder that vengeance, like blood, runs deep and unrelenting.