3rd article in the “No, the Boss Ain’t Ill” series

In the Mafia, perception is reality. A boss who appears weak invites whispers. A boss who disappears too often invites rebellion. And a boss who is sick? He invites murder.

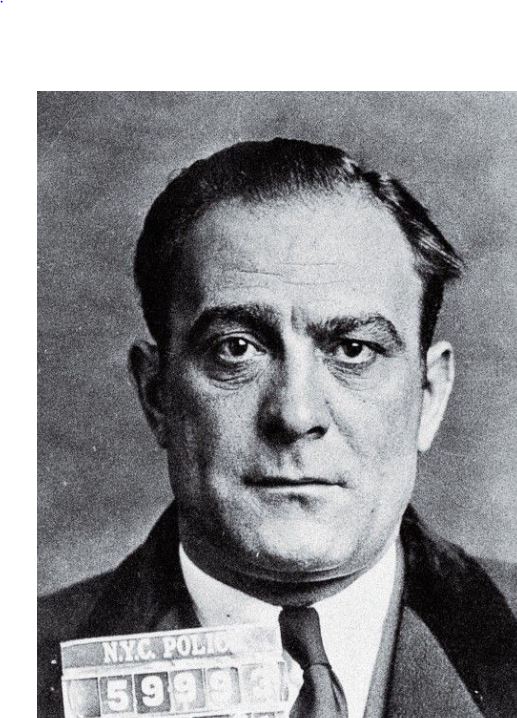

Paul Castellano, heir by marriage and ambition to the Gambino throne, learned this truth the hard way. By the mid-1980s, Castellano was seriously ill, though outwardly he projected the same icy authority he had mastered over decades. To outsiders and rank-and-file alike, he remained the untouchable boss. Inside, only a few knew the truth: Castellano was no longer invincible.

Illness in the Mafia is a currency. It is traded in secrecy, weighed in rumor, and manipulated to consolidate influence. For Castellano, it was both a vulnerability and a shield—hidden from the very people whose loyalty he needed to survive.

Illness as Weakness

Mafia culture has no room for weakness. Even the hint of physical decline can erode authority. The boss is expected to be present, decisive, and terrifying. Every gesture, every glance, is a test of dominance.

Castellano’s health problems—advanced prostate cancer, compounded by decades of stress and poor habits—limited him physically. He spent more time in his Staten Island mansion than on the streets of Manhattan. His meetings became shorter, his travels infrequent. For a man whose reputation was built on meticulous control, these limitations were dangerous.

To admit illness was unthinkable. In the eyes of ambitious street captains and rival families, a sick boss is a weakened boss, and weakness is an invitation.

The Shadow Empire

Castellano’s genius was in the shadows. He ruled through delegation and intermediaries, preferring lawyers, accountants, and trusted capos to do the visible work of enforcement and negotiation. From a distance, his illness could be concealed as careful management.

Only a select few—his bodyguards, trusted aides, and family loyalists—knew the truth. They managed his appearances, scheduled meetings, and controlled access, creating a buffer between Castellano and the men who might use his weakness against him.

This was not loyalty alone. Concealing the boss’s condition allowed underlings to wield subtle power. They filtered information, mediated disputes, and, in some cases, made decisions independently while claiming to act on the boss’s orders.

Illness became a tool, even as it threatened to become a trap.

The Cost of Secrecy

The concealment of Castellano’s condition worked—until it didn’t.

Many of the Gambino family’s street captains did not understand how ill Castellano truly was. They assumed his absence and irritability were signs of arrogance or detachment, not mortality. This misreading of power, combined with his perceived aloofness, created resentment.

John Gotti, one of his ambitious capos, saw a boss who appeared disconnected from the streets, insulated from danger, and, to his mind, replaceable. Gotti did not need proof of Castellano’s illness to justify action; perception alone was enough.

The secrecy around Castellano’s health ironically made him more vulnerable. By hiding weakness, he projected detachment rather than infirmity—and that projection emboldened his enemies.

A Silent War of Influence

Inside Castellano’s inner circle, the concealment of illness created a delicate balance. On the one hand, the fiction of health maintained order and deterred immediate challenges. On the other, it concentrated operational control in the hands of intermediaries, who were free to shape outcomes according to their own interests.

Capos who might have deferred to the boss in public now exercised autonomy in practice. They ran crews, collected tributes, negotiated alliances, and even handled violent matters while ostensibly acting on Castellano’s behalf. In effect, the secrecy of illness created a dual structure: Castellano remained the figurehead, while the underlings managed reality.

This arrangement was sustainable only so long as the illusion endured.

Death in the Shadows

Paul Castellano’s death in 1985 was violent and swift. Gunned down outside Sparks Steakhouse in Manhattan, he was assassinated not merely for power, but because the illusion of control he maintained had fractured.

Illness, secrecy, and perception had all played a role. Castellano’s hidden sickness had made his presence inconsistent and opaque. His detachment was misread as weakness. The very underlings who managed the concealment—Gotti among them—interpreted absence and illness as opportunity.

Had Castellano’s health been transparent, it is possible that a transition of power could have been negotiated quietly, as it had with Gambino decades earlier. Instead, secrecy created a vacuum, and violence filled it.

Lessons from Castellano

Paul Castellano’s story is a grim study in Mafia truth: power is both fragile and performative. Illness undermines authority in subtle ways—through absence, reliance on intermediaries, and misperception.

Underlings benefit from concealing a boss’s illness in the short term. They gain influence, autonomy, and control over information. But that benefit carries a danger: if perception diverges too far from reality, the boss becomes vulnerable to those very underlings.

Castellano’s legacy demonstrates the paradox of concealment. By hiding weakness, he preserved authority—but only superficially. In doing so, he made himself a target for ambition and betrayal, a victim not of illness, but of the very culture that demands invincibility.

The Final Reflection

In the Mafia, a boss is only as strong as he appears. The illusion of invulnerability is a weapon, but also a liability. Paul Castellano wielded it skillfully, but he could not control the perception of those who interpreted absence as weakness.

His sickness, hidden behind layers of loyalists and intermediaries, prolonged his reign, maintained order, and delayed immediate succession. Yet it also planted the seeds of his downfall.

For Castellano, as with other bosses before him, illness was never private. It was a battlefield of perception, secrecy, and ambition. In the end, hiding the frailty of a boss can be a survival strategy—but it can also accelerate the inevitable fall, turning silence into a weapon against the very man it was meant to protect.

References

- Raab, Selwyn. Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires. W.W. Norton & Company, 2005.

- Davis, John H. Mafia Dynasty: The Rise and Fall of the Gambino Crime Family. HarperCollins, 1993.

- Capeci, Jerry. Gotti: Rise and Fall. Berkley Books, 1991.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Paul Castellano Case Files (FOIA-released summaries).

- Maas, Peter. The Valachi Papers. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1968.

- Jacobs, James B. The Mafia and the Machine: The Story of the Kansas City Mob. University of Illinois Press, 2000.