Part of “No, the Boss Ain’t Ill” series

In the Mafia, power is supposed to be absolute or not exist at all. A boss who bleeds is tolerable. A boss who coughs is suspicious. A boss who weakens is already dead—if not in fact, then in the minds of the men around him.

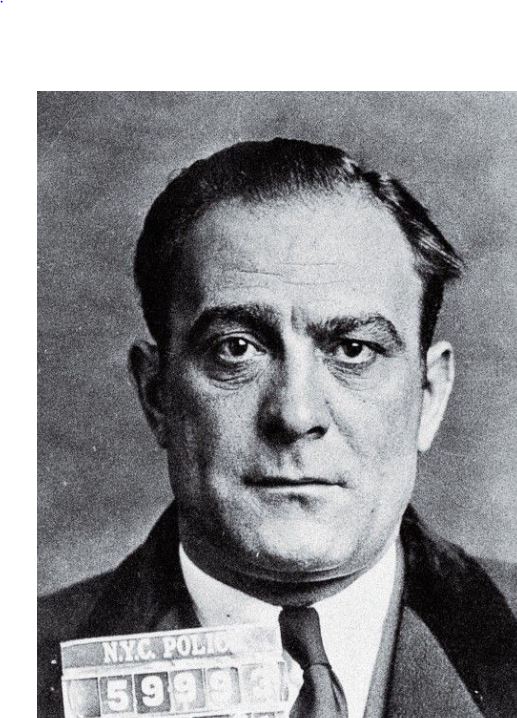

Vito Genovese understood this truth better than most, even as it worked against him.

By the late 1950s, Genovese had clawed his way to the top of the underworld through violence, betrayal, and brute will. He had survived exile, indictments, and rivals who underestimated him. But when his body began to fail—quietly, persistently—he faced an enemy he could not intimidate or eliminate. Illness threatened to do what gunmen and prosecutors had not: expose him as human.

What followed was not an admission of decline, but a campaign of denial. His underlings hid his condition, minimized his frailty, and maintained the illusion of dominance long after the foundation had cracked. They did it for him—but more importantly, they did it for themselves.

Weakness Is a Death Sentence

Mafia culture has no language for sickness. There is only strength and the absence of it. A boss is expected to project control at all times, to settle disputes personally, to inspire fear by presence alone. Illness disrupts that mythology.

A sick boss cannot appear everywhere. He cannot enforce with his own eyes. He relies on intermediaries. And intermediaries, in organized crime, are never neutral. They filter, interpret, and sometimes distort.

Vito Genovese had risen in a world where sick or aging bosses were pushed aside under the guise of “what’s best for the family.” He had watched men lose authority not because they were wrong, but because they were weak. When illness crept into his own life—diabetes, heart problems, physical decline—he knew the stakes.

Admitting weakness would have been an invitation to rebellion.

The Illusion of the Iron Boss

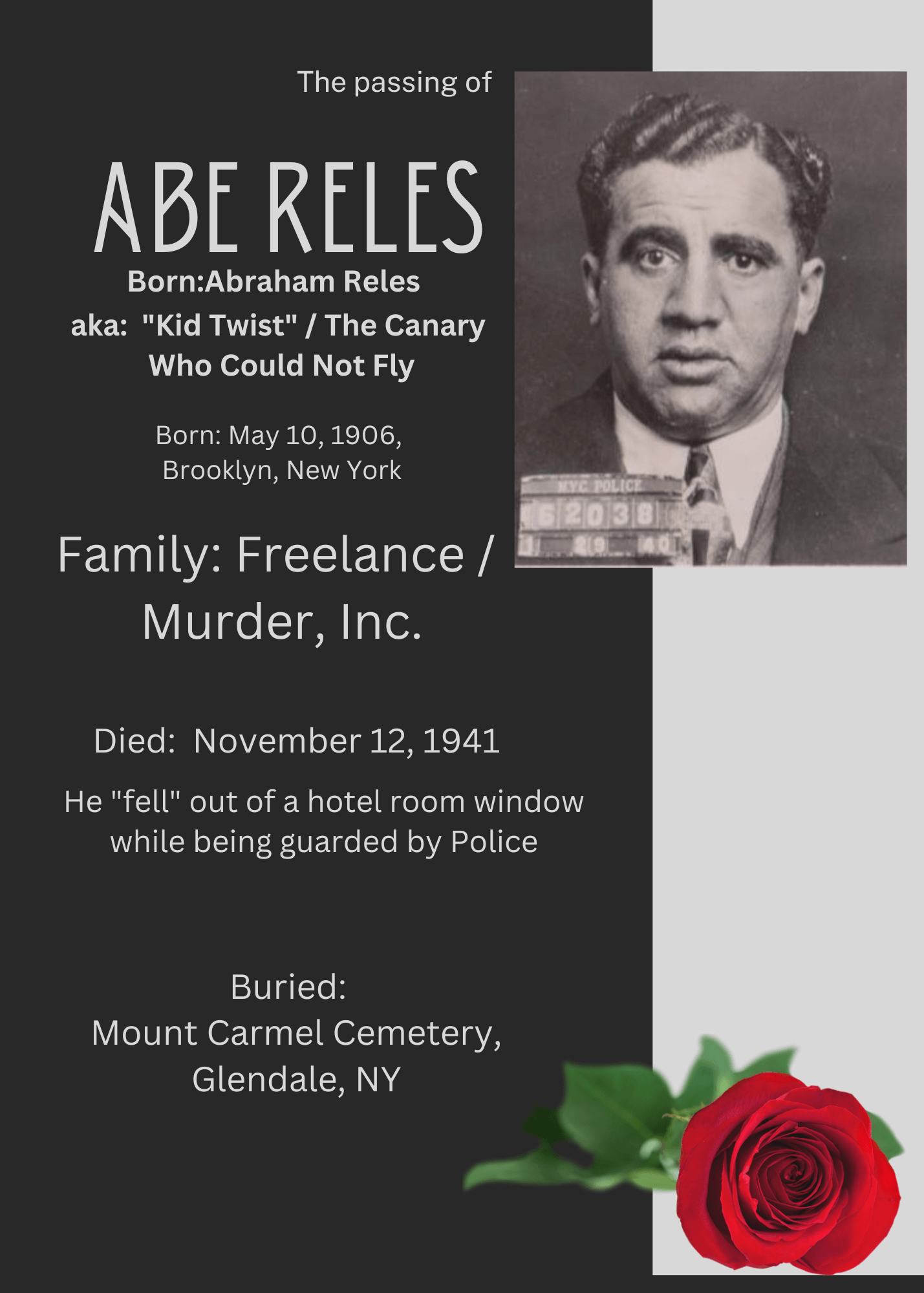

After orchestrating the 1957 assassination of Albert Anastasia, Genovese crowned himself boss of what would later bear his name. On paper, he was at the height of his power. In reality, the timing was cruel.

Genovese was already beginning to slow down. He tired easily. He relied heavily on aides. His health problems were not dramatic, but they were persistent. The kind of problems that do not kill quickly, but erode authority day by day.

To counter this, Genovese and his inner circle leaned hard into projection. Public appearances were carefully staged. Meetings were controlled. Rumors of illness were dismissed as slander spread by jealous rivals.

Inside the family, the message was clear: the boss was fine. Anyone suggesting otherwise was either ignorant or disloyal.

Denial became policy.

Underlings as Gatekeepers

As Genovese’s condition worsened, access to him tightened. Only trusted lieutenants were allowed regular contact. Messages were passed through layers, creating distance between the boss and the rank and file.

This arrangement was sold as efficiency. In practice, it shifted power downward.

Lieutenants became gatekeepers. They decided which problems reached Genovese and which were handled “on his behalf.” They framed decisions as coming directly from the boss, even when interpretation played a role. Over time, the difference became impossible to measure.

For these men, hiding Genovese’s illness was profitable. As long as he remained boss in name, no open power struggle could erupt. Ambitious captains were forced to wait. Rivals were kept guessing.

The underlings gained influence without taking responsibility.

Fear Without Presence

Genovese’s reputation carried weight, but reputation alone has limits. Fear must be refreshed. It requires reminders.

As illness reduced Genovese’s visibility, enforcement became delegated. Orders were carried out by proxies. Punishments were delivered without the boss being seen.

This worked—until it didn’t.

Some capos began to sense the gap between the myth and the man. Genovese still ruled, but increasingly from a distance. His authority depended on loyalty that had not yet been tested.

To prevent that test, his underlings doubled down on secrecy. Any sign of physical weakness was explained away. Missed meetings were blamed on strategy. Hospital visits were concealed or minimized.

The illusion held, but it required constant maintenance.

The Apalachin Disaster

The illusion shattered in November 1957 at the infamous Apalachin meeting.

While not directly caused by Genovese’s illness, the event exposed his overconfidence and miscalculation—traits often sharpened by declining health and isolation. The meeting drew unprecedented law enforcement attention and humiliated the Mafia nationally.

For Genovese, it was a blow that accelerated everything. Stress compounded his health issues. His enemies smelled blood.

Still, his inner circle insisted he remained strong. Publicly, nothing changed. Privately, contingency plans began to form.

Illness had not removed Genovese from power, but it had narrowed his margin for error. In the Mafia, that is often fatal.

Prison: The Final Exposure

In 1959, Genovese was convicted on narcotics charges and sentenced to prison. Behind bars, denial became harder to sustain.

Prison strips away theater. There are no staged appearances, no controlled rumors. Physical decline becomes visible.

From his cell, Genovese attempted to rule as before—issuing orders, settling disputes, asserting authority. His underlings continued to invoke his name, insisting he remained the true boss.

But something had changed.

Illness plus imprisonment was a double weakening. His body was failing, and his reach was limited. The men around him adapted accordingly.

Power began to diffuse.

How Underlings Profited from the Lie

Even as Genovese’s health deteriorated in prison, his underlings maintained the fiction of control. This benefited them in specific ways.

First, it prevented chaos. Open acknowledgment of a weakened boss would have triggered immediate jockeying for position.

Second, it allowed them to operate autonomously while claiming legitimacy. Decisions made “for the boss” carried authority without direct accountability.

Third, it bought time. Time to build alliances. Time to position themselves for the inevitable post-Genovese era.

The denial of illness was no longer about protecting Genovese. It was about managing succession without bloodshed.

The Quiet Transfer of Power

As years passed, Genovese’s influence faded, though his title remained. A ruling panel effectively took over daily operations. His name was still used, but his control was symbolic.

This transition happened without a formal announcement, without violence, and without public acknowledgment of decline. It was the underworld’s version of a quiet coup.

Genovese died in prison in 1969, still officially boss, still feared in legend if not in fact. The illusion had outlived the man.

The Cost of Denial

Vito Genovese did not die violently, but he did not die powerful either. His refusal to confront weakness—physical or political—left him isolated, ruling in name while others ruled in practice.

His underlings survived and prospered. Some would shape the future of the Genovese family for decades. They learned the lesson well: perception matters more than truth.

Illness was hidden not out of mercy, but out of necessity.

Final Reflection

In the Mafia, illness is never just illness. It is a signal flare, a warning that power may be up for grabs.

Vito Genovese tried to deny that reality. His underlings exploited the denial. Together, they prolonged a fiction that kept the peace and preserved profits—but at the cost of genuine authority.

Genovese’s reign ended not with gunfire, but with erosion. Power slipped away quietly, hidden behind layers of loyalty and lies.

In the end, the greatest crime was not weakness—but pretending it did not exist.

References

- Raab, Selwyn. Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America’s Most Powerful Mafia Empires. W.W. Norton & Company, 2005.

- Maas, Peter. The Valachi Papers. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1968.

- Critchley, David. The Origin of Organized Crime in America: The New York City Mafia, 1891–1931. Routledge, 2009.

- U.S. Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. Organized Crime and Illicit Traffic Hearings, 1957–1963.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. Vito Genovese Case Files (FOIA-released summaries).

- Davis, John H. Mafia Dynasty. HarperCollins, 1993.