In the spring of 1931, a storm of blood swept through the underworld. It was fast, calculated, and silent. The victims were many — old-school Mafia dons, clinging to outdated codes of Sicilian loyalty and despotic power. The executioners were young, American-born, and ruthless. At the center of it all stood Charles “Lucky” Luciano, the man who would soon be crowned the modern architect of American organized crime.

That brutal purge would later be known as The Night of the Sicilian Vespers, a term borrowed from the 1282 rebellion in Sicily that saw thousands of French occupiers slaughtered in a single evening. History, in Luciano’s hands, would echo with grim poetry.

The Rise of a Lucky Man

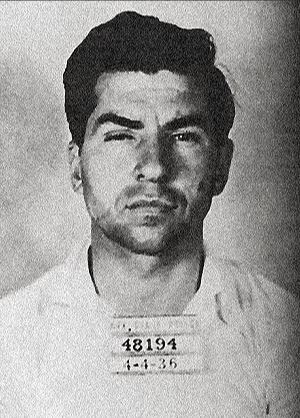

Born Salvatore Lucania in 1897 in Lercara Friddi, Sicily, Luciano emigrated to New York with his family at age ten. From the streets of the Lower East Side, he quickly climbed the ranks of organized crime — first as a young thug running errands for Five Points Gang, later as a trusted associate of Arnold Rothstein, the man who taught Luciano how to marry violence with business.

By the late 1920s, Luciano had grown disillusioned with the old-world ways of the Mafia. The structure was rigid, the leadership paranoid and erratic, and profits were hampered by outdated rituals and clan-based loyalty. The top boss — Giuseppe “Joe the Boss” Masseria — epitomized that decaying model: greedy, brash, and stuck in a Sicilian past that didn’t fit the capitalist machinery of modern American crime.

To Luciano, Masseria represented a cancer within the organization. But if he was going to remove the cancer, he’d need to kill the entire old guard.

The Mafia’s Civil War

The spring of 1930 marked the beginning of what would be called The Castellammarese War, named after the town of Castellammare del Golfo in Sicily, home to Masseria’s rival, Salvatore Maranzano. It was a bloody turf war waged across New York City, claiming dozens of lives in the battle between Masseria’s “Mustache Petes” and Maranzano’s Castellammarese faction.

Luciano played both sides like a maestro. While still officially loyal to Masseria, he began quietly meeting with Maranzano and his younger allies, men like Vito Genovese, Joe Adonis, and Albert Anastasia. These were men who, like Luciano, saw the future in a more modern, streamlined syndicate — one that embraced multi-ethnic alliances, avoided unnecessary bloodshed, and focused on profit over pride.

The death knell for Masseria came on April 15, 1931. Luciano lured him to lunch at Nuova Villa Tammaro in Coney Island. After finishing a game of cards and a plate of pasta, Luciano excused himself to the bathroom. Minutes later, gunmen stormed in — Anastasia, Genovese, Adonis, and Bugsy Siegel — and gunned Masseria down, leaving his corpse slumped at the table, a cigar still burning between his fingers.

With Masseria gone, Maranzano was named capo di tutti capi — boss of all bosses. But Luciano was not content to simply trade one tyrant for another.

Night Falls on the Old Guard

Maranzano’s reign was brief. Just weeks into his rule, he began plotting to eliminate Luciano and his allies, fearing the young turk’s growing influence. He called Luciano to a meeting, intending to have him killed.

But Luciano got word of the setup through his Jewish associate, Meyer Lansky. The hunter became the hunted.

On September 10, 1931, Luciano struck back. Disguised as government agents, four of Luciano’s men entered Maranzano’s office at the Helmsley Building. They announced a “raid,” disarmed Maranzano’s guards, and stabbed him repeatedly before shooting him in the face.

What followed in the next 48 hours was the dark symphony of what has been called The Night of the Sicilian Vespers — a coast-to-coast extermination campaign that wiped out Maranzano’s loyalists and any other old-school bosses who posed a threat to the new order.

In New York, in Buffalo, in Chicago, in Philadelphia — men with names like Scarpellino, Ferrigno, Traina, and Milano were hunted and executed. The hits were quick, efficient, and often never solved. Bodies were found riddled with bullets. Others simply vanished.

It wasn’t just a purge. It was an exorcism.

The Syndicate Is Born

In the aftermath of the bloodletting, Luciano emerged as the undisputed kingmaker of American organized crime. But rather than take the title of capo di tutti capi — a position he believed created too many targets — Luciano abolished it entirely. In its place, he created The Commission.

The Commission was a revolutionary governing body composed of the heads of the Five Families in New York, plus representatives from Chicago (led by Al Capone’s outfit) and Buffalo. It functioned as a board of directors, settling disputes, managing territory, and coordinating nationwide operations in narcotics, gambling, labor racketeering, and prostitution.

Luciano’s vision was clear: the Mafia would be less like a feudal kingdom and more like General Motors — decentralized, efficient, and lucrative. The days of the mustache-twirling tyrants were over.

Shadows and Echoes

Some questioned the morality of Luciano’s purge — as though morality ever had a place in organized crime. But to the younger generation of mobsters, Luciano was a visionary. He recognized that clinging to Sicilian tribalism was bad for business. In a world defined by Prohibition, corruption, and explosive capitalist growth, there was no room for ego or nostalgia.

The Night of the Sicilian Vespers was brutal, but it was also a necessary evil — at least in Luciano’s mind. In killing the past, he made way for a syndicate that would endure for decades, shaping American politics, labor, and commerce from the shadows.

Luciano would eventually be brought down by federal prosecutors in the 1930s and deported to Italy in 1946. But even in exile, his fingerprints remained on the machine he had built.

He once said, “There’s no such thing as good money or bad money. There’s just money.” That ethos — cold, modern, merciless — was the foundation of the American Mafia he helped forge.

Author’s Note: The Night of the Sicilian Vespers was not a single night but rather a symbolic term for a rapid, methodical cleansing of the old-world mobsters. While details vary due to the secretive nature of the Mafia, historians agree it marked a transformational shift in American organized crime. Lucky Luciano didn’t just change the game. He invented a new one.