The Great Depression created its share of monsters, but few were as twisted, unpredictable, and brutal as Verne Miller. Once a decorated soldier and county sheriff, Miller’s life veered off into the shadows until he was no longer a man at all—just a hired gun, a butcher, a specter trailing bodies from South Dakota to Detroit. His rise and fall wasn’t just another gangster tale; it was a slow, grinding transformation from lawman to outlaw, from public servant to public enemy, until his own friends in the underworld decided his only future was death in a ditch.

The Sheriff Who Snapped

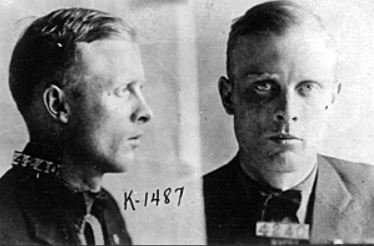

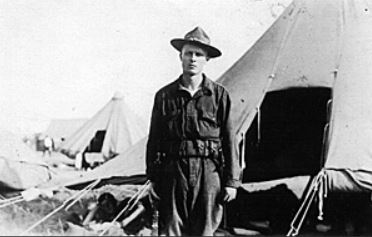

Vernon Clate Miller was born in South Dakota, 1896—dust, poverty, nothing worth writing home about. The Army gave him a taste of glory. He fought in France, wore his Croix de Guerre like armor, came home with scars, gas burns in his lungs, and a thirst for order. For a while, he played it straight. Sheriff of Beadle County. A badge. A gun. A reputation for being hard, unbending, a man who took no bribes.

But authority never came easy to him. The whispers started quick: money missing, women on the side, a mean streak that spilled into violence. In 1922, the bottom dropped out—Miller ran off with county funds, left his badge behind, and set himself on the road that would end in blood.

By 1923, he was in prison, wearing stripes. By 1924, he was back out, free—and different. Prison had stripped away the last of his conscience. Whatever lines still kept him human had vanished.

A Killer for Hire

Prohibition turned Miller into something darker. He ran whiskey, muscled bootleggers, and fell into the orbit of the Purple Gang in Detroit and Chicago Outfit muscle. He wasn’t flashy like Dillinger or romantic like Bonnie and Clyde. Miller was something scarier: cold, efficient, always ready to pull the trigger.

He carried out killings in hotel rooms, cornfields, back alleys. He didn’t brag. He didn’t smile. He didn’t hesitate. The underworld had a nickname for men like him: mechanics. Miller was a mechanic of death.

One story tells it best: when Capone’s allies were hit in a Wisconsin resort, Miller went hunting. He found the suspected shooters in a Fox Lake hotel, walked inside, and cut them down without a word. Three dead in seconds. Miller strolled back out like he’d only paid the check.

Bank robberies followed—Sherman, Texas. Willmar, Minnesota. Shootouts with police. Bodies piling up in his wake. But his most infamous moment came in 1933, at a train station soaked in gun smoke and blood.

The Kansas City Massacre

June 17, 1933. Union Station, Kansas City. The feds had bank robber Frank Nash in custody. He was shackled, under guard, ready for transport. But Miller had other plans.

The plan was simple: ambush the cops, free Nash, and vanish. But simple plans rarely survive a Tommy gun. Miller and his crew—men like “Pretty Boy” Floyd and Adam Richetti—waited outside. When the prisoners emerged, the street erupted in automatic fire.

Nash’s head was opened by a bullet before he could take a step. Four lawmen collapsed in the hailstorm of lead. Blood sprayed across the station walls. When it was over, bodies lay twitching on hot concrete, and Miller was already gone.

The papers called it The Kansas City Massacre. It was more than a bloodbath; it was a declaration of war. The underworld had murdered federal agents in broad daylight, and J. Edgar Hoover made Miller his personal vendetta.

A Man on the Run

After Kansas City, Miller wasn’t just a fugitive—he was a ghost hunted by both sides. Hoover’s new FBI agents wanted him in chains. But the mob wanted him gone, too. He had become sloppy, dangerous, a liability. Miller didn’t just make headlines—he made messes.

He shot a man connected to Abner “Longy” Zwillman, one of the East Coast’s heavy hitters. That was suicide. In the mob, you didn’t kill your host’s man and walk away. Miller was marked.

He drifted through Chicago, Detroit, Newark, living in safe houses, always armed, always paranoid. His girlfriend was arrested. His friends vanished. Doors that once opened to him now slammed shut. Miller was running out of time.

The Torture in Detroit

On November 29, 1933, a motorist spotted a bundle on the side of the road near Detroit. It wasn’t laundry—it was Miller.

Naked. Bound with clothesline. Skull split open from a claw hammer. Thirteen strikes. His body covered in bruises, burns, evidence of a beating that went on for hours. Whoever killed him didn’t just want him dead—they wanted him erased.

The cops pieced it together: it was payback, pure and simple. The mob had taken him apart, one blow at a time, until the mechanic of death was nothing but discarded meat.

The Aftermath

Miller’s death closed the book on one of the bloodiest chapters of Depression-era crime. The Kansas City Massacre fueled the FBI’s rise to power. Federal agents were now armed, ruthless, and empowered to hunt criminals across state lines. In a sense, Miller’s ghost created the modern FBI.

As for Miller, he left no legacy but fear. No romantic outlaw ballads, no Robin Hood myths. He was a lawman who betrayed his badge, a soldier who betrayed his country’s honor, a killer who finally learned that violence always circles back.

The ditch in Detroit wasn’t just a grave—it was justice, mob-style.