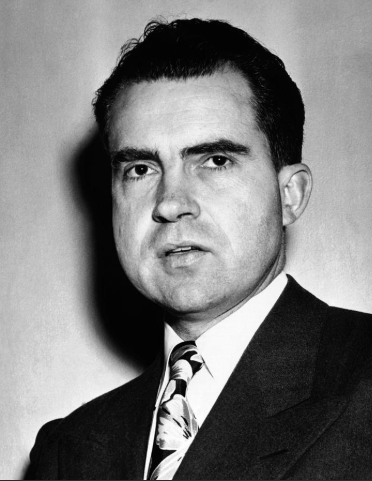

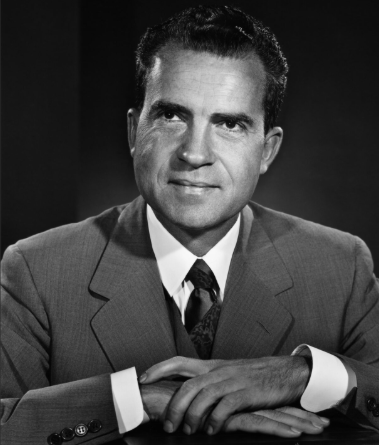

In the fog of American history, few faces peer back as defiantly—or as infamously—as that of Richard Milhous Nixon. The 37th President of the United States, once seen as a stoic Cold War warrior and a cunning political strategist, ultimately became synonymous with scandal, secrecy, and denial. His infamous declaration—“I am not a crook”—was less a defense than a final, desperate gasp to escape the undertow of Watergate. But Nixon’s web of denial wasn’t woven around Watergate alone. For years, rumors swirled around backchannels of power, linking his administration, his campaigns, and perhaps even Nixon himself to the dark underbelly of organized crime.

This is the story of Richard Nixon—the man who denied everything—and the shadows he couldn’t outrun.

The King of Denial

It was November 17, 1973, at a press conference in Orlando, Florida, when Nixon, under mounting pressure, gave the world the soundbite that would come to define his legacy:

“People have got to know whether or not their president is a crook. Well, I am not a crook.”

He said it with steely eyes and a bitter curl in his lips. But the damage was done. The public didn’t believe him anymore. His words rang hollow in the wake of revelations: bugged offices, hush money, a burglary orchestrated from inside the White House. Nixon’s own Oval Office tapes, dripping with paranoia, racism, and obstruction, were becoming the guillotine he couldn’t stop.

He denied wrongdoing to the very end. Even after his resignation—the first and only of a U.S. president—he maintained he had done nothing illegal. “Mistakes were made,” he would admit. But he was no criminal. Never that.

What Nixon refused to confront was the moral rot beneath the surface—a rot he helped cultivate. But the rot wasn’t confined to Watergate. It extended beyond Washington, into the smoke-filled rooms of America’s underworld. The Mafia—organized crime families who had infiltrated labor unions, gambling rings, drug pipelines, and even political campaigns—lurks in the peripheral vision of Nixon’s story. And some say it wasn’t just peripheral.

Nixon and the Mob: Strange Bedfellows

The links between Nixon and organized crime have long been whispered among historians and investigative journalists. While never proven in a court of law, the circumstantial evidence paints a murky, unsettling picture. The allegations aren’t mere conspiracy—they stem from testimonies, financial records, and criminal investigations that never quite made it to primetime headlines.

One of the most persistent threads winds its way through Nixon’s early political career and into the casino pits of Las Vegas. Nixon’s connection to Charles “Bebe” Rebozo, his longtime confidant and personal banker, raises questions. Rebozo, a Florida businessman of Cuban descent, had ties to organized crime figures and was known to launder money through real estate and banks. He was also Nixon’s drinking buddy, travel companion, and—according to some reports—the bagman who handled suspicious cash transactions.

In 1972, investigative journalist Jack Anderson alleged that the Mob laundered money through Nixon’s re-election campaign. Reports also claimed that Nixon accepted a secret $100,000 donation from Howard Hughes, a reclusive billionaire with deep mob ties, delivered by Rebozo. Though the money trail vanished into shadows, the stench of corruption never faded.

And then there’s the Teamsters. Under the leadership of Jimmy Hoffa—who famously “disappeared” in 1975—the International Brotherhood of Teamsters was a powerful political force with deep Mafia entanglements. Nixon commuted Hoffa’s prison sentence in 1971, years before he was eligible for parole. Why? Some speculate it was a payoff—a favor called in by mob bosses who helped deliver votes in key states. Hoffa’s freedom didn’t last, but Nixon got what he wanted: a second term.

Casino Connections and the Black Book

Las Vegas, 1970s. A city powered by slot machines, secrets, and silent partners. The Mafia had built the Strip, one skimming dollar at a time. Casinos were cash machines—legal laundering stations. And Nixon was no stranger to the neon lights.

One of the more fascinating anecdotes involves Nixon’s vice president, Spiro Agnew, who was forced to resign in 1973 for taking bribes. Agnew had ties to developers and mob-linked businessmen. But Nixon’s administration didn’t just tolerate these connections—they seemed to thrive on the quiet influence of criminal syndicates who knew how to make problems disappear.

In the Nevada Gaming Control Board’s infamous “Black Book”—a list of individuals banned from entering state casinos—several names from Nixon’s circle of donors and allies appeared. These were not choir boys. They were button men, fixers, and money men. Men who made politicians dance like marionettes.

Was Nixon their puppet? Or their partner?

Watergate: A Mob Mentality

If you strip away the marble pillars and patriotic speeches, the Watergate scandal reads more like a Mafia operation than a political scandal. There were break-ins, hush money, secret meetings in garages, and a “boss” who ruled through fear and loyalty. Nixon’s obsession with control, his disdain for the press, his need to punish enemies—these are hallmarks of mob psychology.

He had an “enemies list.” He used the IRS and the FBI like weapons. He installed taping systems to catch everyone—even his own allies—in compromising moments. Loyalty was currency in Nixon’s White House, and betrayal was treated as treason. In a sense, Nixon didn’t just run an administration—he ran a criminal enterprise. But unlike the dons of the Mafia, Nixon had to operate under the veneer of democracy. He lied not only to the public but to himself.

Even after the walls closed in, Nixon maintained the mobster’s mantra: Deny. Deny. Deny.

The Fall—and the Fantasy

When Nixon boarded the helicopter on August 9, 1974, he gave one last awkward wave, the double-V victory salute that had once defined his political rise. It looked less like triumph and more like delusion. He left behind a gutted presidency, a divided nation, and a gaping wound in American trust.

But he never admitted guilt.

Years later, in his post-resignation interviews, Nixon tried to rehabilitate his image. He wrote books. He advised presidents. He gave television interviews, including the famous Frost/Nixon sit-down where he came closest to a confession. But even then, Nixon danced around culpability, refusing to say the one thing that could have set his legacy on a redemptive path:

“Yes, I broke the law.”

That would have taken more courage than he ever possessed.

Legacy of Denial

Richard Nixon died in 1994, mourned by the political establishment he once betrayed. By then, America had grown weary of scandal, and the details of Watergate had been absorbed into textbooks and trivia nights. But the deeper story—the real story—remains partly buried.

Was Nixon merely a paranoid politician who overreached? Or was he something darker—a man who blurred the lines between governance and gangsterism? A president whose denials were not just about saving face, but about shielding deeper, darker truths?

The Mafia never needed to run for office. They had people like Nixon to do that for them.

Conclusion

Nixon’s greatest crime may not have been Watergate. It was convincing the American people that he was ever clean to begin with. That infamous phrase—“I am not a crook”—echoes through history not as a defense, but as a damning self-indictment.

In the end, Nixon’s story is not one of guilt versus innocence. It’s about the toxic alchemy of power and fear, secrecy and silence. And it’s about how far a man will go to deny the truth—even as it stares him in the face from the bottom of a mob ledger or the center of a wiretap.

And perhaps, just perhaps, the real crooks never needed to say a word. They had Nixon to do the talking.