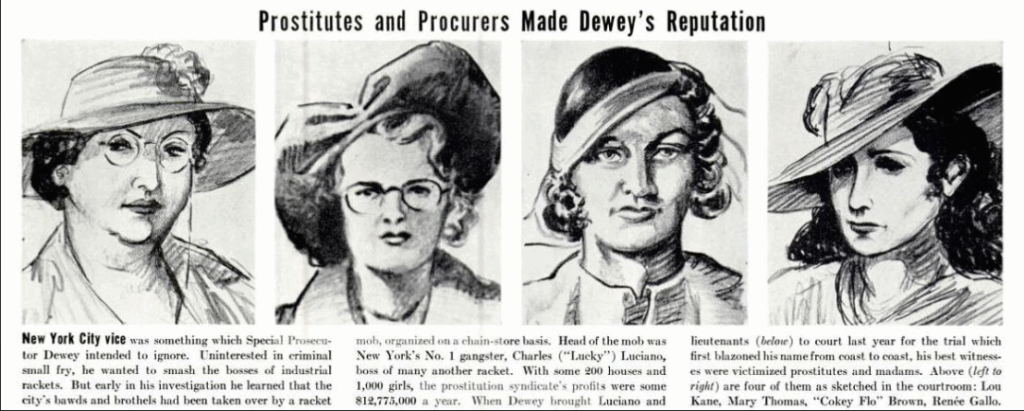

They were hustlers, addicts, madams, ghosts in the neon: Florence “Cokey Flo” Brown, Nancy Presser (aka Genevieve Flesher), Mildred Harris, Thelma Jordan, and Joan Martin. For a few hot weeks in the spring of 1936, they stood under courtroom lights and pointed at the most notorious man in New York. Thomas E. Dewey—hawk-eyed, jaw like a paper-cutter—made sure the jury believed them. Then the lights went out, the doors slammed, and everyone had to live with what happened.

How Dewey built the case

Dewey’s office didn’t invent the sex trade; it industrialized a prosecution strategy against it. After mass raids swept up more than a hundred women from brothels across the city, the state held many of them on crippling bail inside Dewey’s own offices, funneling them toward cooperation. The idea wasn’t to gather sympathy for sex workers; it was to prove that a “combination” of pimps and bookers—answering, prosecutors said, to Luciano—ran prostitution like a chain store. The star was Florence “Cokey Flo” Brown, a heroin-addicted ex-madam whose testimony gave the jurors a quote they could never un-hear: Luciano—she swore—bragged he would “organize the cathouses like the A&P,” a chain-store syndicate of flesh.

Brown wasn’t alone. Dewey marched in a parade of women who’d lived inside the city’s vice economy. Nancy Presser said intimacy and proximity gave her a window on Luciano’s world. Mildred Harris backed the “combination” narrative. Thelma Jordan described the terror that kept girls from talking—what happened to the ones who did, how they were burned and beaten. Joan Martin, a madam, swore to shakedowns by the ring’s muscle. Each woman added a brick to Dewey’s wall; together, they made it look unscalable.

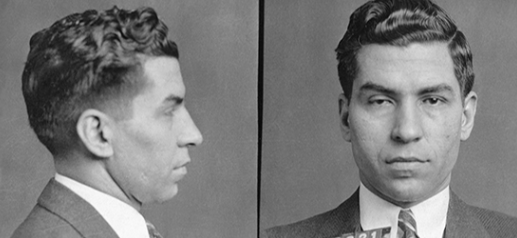

When Luciano gambled and took the stand—thinking he could charm the panel—Dewey cut him to ribbons on cross. On June 7, 1936, after two weeks of testimony, the jury convicted Luciano on 62 counts of compulsory prostitution; he drew 30 to 50 years. It was the headline that made Dewey a household name.

What came after the verdict

Justice doesn’t end with a gavel; it echoes. Almost as soon as Sing Sing’s gates clanged behind Luciano, the witnesses scattered. Brown and Harris surfaced in California, chasing money, sobriety, and peace. Presser vanished to Europe. And then, one by one, several of them reappeared with affidavits. They said they’d lied. They said they’d been pushed. They said the truth—whatever it was—hadn’t made it into the record.

Contemporaneous reporting in The Atlantic—hardly a friendly brief for Luciano—described a subterranean war for the women’s allegiance after the trial: operatives, cures for addiction, expenses paid, and the drumbeat for recantations. Brown and Harris, once detoxed at the expense of a Luciano-connected lawyer, swore their trial testimony was false. When Presser returned from Europe, she, too, made an affidavit undercutting her words on the stand. The magazine painted a grim picture of witness handling on both sides.

The most lurid allegation in the post-trial fog was that two marquee witnesses—Presser and Jordan—were treated to a three-month European vacation under the auspices of people tied to the prosecution. That claim appears in later secondary summaries and in a surviving affidavit file cited by researchers; it has been repeated often enough to have a life of its own, even as historians argue about its provenance and spin. What’s undeniable is that multiple key witnesses recanted—and that the recantations became part of the Luciano legend.

Were they “used” to frame him?

This is the radioactive question, the one still humming in the archives. Eunice Hunton Carter, the formidable assistant DA who architected the prostitution investigation, believed organized crime sat on the money pipeline of New York’s brothels; Dewey believed he could prove that pipeline led to Luciano. Critics—among them later scholars and contemporaries like Polly Adler and Joseph Bonanno—have called the state’s direct link to Luciano thin, more extortion-by-brand-name than hands-on management. Selwyn Raab, a careful chronicler of the Five Families, called Dewey’s evidence “astonishingly thin” for the specific theory of control. But “thin” isn’t “nothing,” and courtrooms don’t grade on academic caution.

What, then, of the five women at the center of it? “Cokey Flo” Brown was the accelerant—addicted, angry, and unforgettable to jurors. Presser, glamorous in the press accounts, came and went like smoke, her recantation arriving from overseas. Mildred Harris’s story zigzagged through addiction and media. Thelma Jordan radiated fear on the stand, talking about what the combination did to girls who talked. Joan Martin brought the madam’s ledger—money, beatings, names. If you wanted to believe Dewey, they were survivors finally telling the truth. If you wanted to believe Luciano, they were stage props—frightened, leveraged, sometimes rewarded—for a prosecutor with a future to build.

The unsettling answer is that two things can be true at once: women trapped in a violent, exploitative economy can also be steered by the state to say what the state needs. Dewey’s office held many of them on high bail, housed them under guard, and managed their movements while the case ripened. That caretaking could look like protection—or pressure—depending on which side of the bars you stood.

The legal system’s answer

Courts are built to resolve doubts—brutally, finally. Luciano appealed, arguing (among other things) that the witness recantations and the prosecution’s methods undermined the verdict. The New York Appellate Division affirmed the convictions in July 1937. The Court of Appeals later affirmed as well and rejected attempts to build a new trial on the recantation claims. The United States Supreme Court denied review in 1938. There was no reversal, no grand judicial confession that the case had been a bridge too far. The verdict stood.

Years later, wartime “Operation Underworld” rumors and the politics of postwar New York helped turn Luciano into a myth with a hundred different endings; none of them erased the paper record that mattered. When he finally left a New York prison, it wasn’t because a court found Dewey’s case rotten; it was because the governor commuted the sentence and deported the most famous inmate in the state. The law had spoken, and it never took back the words.

The five, revisited

It’s easy to flatten these women into archetypes: the addled madam, the kept girl, the frightened worker, the calculating turncoat. It’s harder—and more honest—to read them as people pulled into a contest waged by men far more powerful than they were. Dewey’s team needed them to be credible enough to convict; Luciano’s camp needed them to be compromised enough to recant. Addiction, poverty, violence, and the pressure of the state sat on their shoulders either way.

What remains is the uncomfortable residue of a “win.” Dewey got his headline. Luciano got his number. And five women—Brown, Presser, Harris, Jordan, Martin—got a lifetime of people arguing over whether their voices were weapons or warnings.