Where truth gets buried with the body

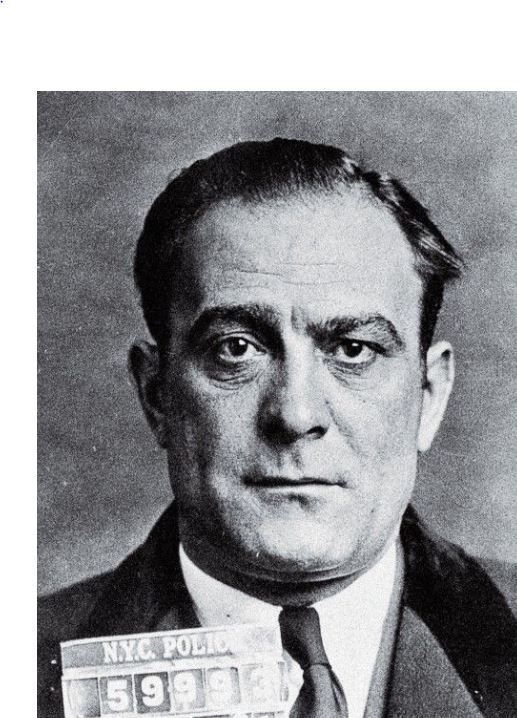

On the bitterly cold morning of February 25, 1959, Abner “Longie” Zwillman—once crowned the “Al Capone of New Jersey”—was found dead in the basement of his lavish West Orange home. The body of one of America’s most powerful and politically connected mobsters dangled from a plastic clothesline. Authorities moved quickly. Suicide, they said. Depression. Fear of federal subpoenas. End of story.

But to anyone who knew Zwillman—really knew him—the story didn’t ring true. He wasn’t some low-level hood about to crack under pressure. Zwillman was a mob institution, a man who had weathered every storm since the bootlegging days of Prohibition, built a criminal empire from the gutters of Newark to the boardrooms of Hollywood, and shared his bed with Jean Harlow while greasing the palms of U.S. Senators. He wasn’t a snitch. And he didn’t hang himself.

This wasn’t suicide. This was a message. And it came from the very top: Vito Genovese.

A Man Too Big to Fall

Zwillman was a mobster’s mobster. Born in Newark in 1904, he turned from petty crime to liquor distribution during Prohibition, amassing millions while the country staggered under the weight of the Great Depression. He bought influence the way other men bought Cadillacs. Politicians, judges, even police departments bent under his reach. By the 1940s, Zwillman was deeply embedded in labor racketeering, gambling, and Hollywood extortion. He even helped pave the way for organized crime’s infiltration of the motion picture industry.

But his biggest strength was his silence. Zwillman never cracked. He beat indictments, outmaneuvered the FBI, and kept his mouth shut even as friends flipped or vanished.

So why would a man like this, at the height of his wealth and power, suddenly hang himself with a cheap plastic clothesline?

The answer is simple: He didn’t.

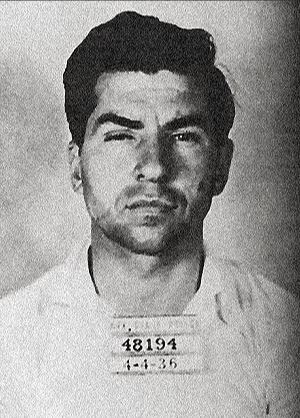

Genovese’s Bloody Rise

To understand Zwillman’s murder, you need to understand Vito Genovese’s thirst for control. After years of exile in Italy, Genovese returned to the U.S. in the mid-1940s and began carving his way back to power with a butcher’s precision. His ambition: complete control of the American Mafia.

In May 1957, Genovese made his first major move by ordering the assassination attempt on Frank Costello, the reigning boss of the Luciano (later Genovese) family. Costello survived but stepped down, knowing the message was loud and clear.

Then came Albert Anastasia, the Mad Hatter of Murder, Inc. A powerfully feared force who had to be removed for Genovese’s plan to succeed. On October 25, 1957, Anastasia was shot to death in a Manhattan barbershop in broad daylight. The next month, Genovese tried to crown himself King of the Underworld at the now-infamous Apalachin Meeting, where over 100 mafiosi were rounded up in a police raid that blew the lid off the Mafia’s existence in America.

It was a disaster.

The FBI was now fully awake, and the underworld was in chaos. Genovese’s heavy-handed tactics and sloppiness had made him a target—not just for the law, but for his fellow mob bosses. He needed a scapegoat. A corpse. A warning.

Zwillman’s Crime? Loyalty

Abner Zwillman had been a Costello man—part of the old guard. He was respected, independent, and rich. He controlled gambling, labor unions, and legitimate businesses across the Northeast. His political connections ran deep, and his code of silence even deeper. He was everything Genovese wasn’t: subtle, calculating, and diplomatic.

Worse, Zwillman still held enormous sway in New Jersey and beyond. While Genovese was scrambling to consolidate power, Zwillman remained untouchable—until the noose of subpoenas began tightening around him.

To the paranoid Genovese, that was enough. Zwillman, despite his reputation, might flip. And even if he wouldn’t, others might think he would. That was all it took. In the Mafia, perception is death.

The Broken Thumb

When Zwillman’s body was found, the official story said he had become despondent. The feds were closing in. Depression. A moment of weakness.

But the autopsy told a different story.

Zwillman had a broken thumb—a detail authorities tried to wave off, but which mob insiders knew better than to ignore. It wasn’t an accident. A broken thumb meant one thing: a struggle. Someone had tried to get away. Or been restrained. Or punished.

There were other oddities, too. His feet were nearly touching the floor, which raised questions about whether he could have truly hanged himself. The clothesline was thin and inadequate for a man of his size. There was no suicide note. No signs of mental deterioration. Just silence—and a corpse that spoke volumes to anyone who understood the code.

This was a staged scene. A carefully manufactured lie. It was suicide made to look like suicide.

A Message Delivered

The timing couldn’t have been more calculated. Zwillman had recently been subpoenaed again—yet had given no indication of cooperating. His businesses were under pressure, yes, but his life wasn’t unraveling. Not unless someone was helping unravel it.

His death served two purposes:

- It eliminated a powerful rival who could rally opposition against Genovese.

- It sent a chilling message to any other boss thinking of standing in the way or speaking out.

Zwillman’s death was clean, surgical, brutal—like the others Genovese ordered. But unlike Anastasia or Costello, whose deaths were loud and public, Zwillman’s demise was whisper-quiet. The kind of killing that makes you question everything. The kind that erases a man while letting the world pretend he left by choice.

Aftermath

Genovese wouldn’t enjoy his throne for long. In 1959—the same year Zwillman died—Genovese was convicted on drug trafficking charges that many believe were orchestrated by rivals like Carlo Gambino and Lucky Luciano. He would die in prison a few years later, a boss in name only, forgotten by the very machine he tried to command.

Zwillman, on the other hand, remains a myth. A businessman, a killer, a politician, a ghost. His death, like his life, sits at the murky crossroads of truth and power, justice and violence.

To this day, few speak of what really happened in that West Orange basement.

But among those who know, there’s no doubt: