For decades, the Mafia was cloaked in myth—an underworld of cigar smoke, whispered threats, and bodies in the trunk. But the real story of the mob’s unraveling wasn’t written in blood. It was written in numbers. The glint of gold chains and Cadillac grilles faded not under the weight of bullets, but under the weight of subpoenas, financial records, and accountants who could read between the lines.

The true weapon of law enforcement’s war on organized crime wasn’t brute force—it was the ledger.

The House Always Wins—Until It Doesn’t

By the 1960s and ’70s, the Mafia was more than a criminal enterprise—it was a shadow economy. With roots in the Sicilian tradition of omertà (a code of silence), the American Mafia had become a tightly woven network of “families” profiting from illegal gambling, loan sharking, construction rackets, labor union infiltration, and drug trafficking. Their business model was simple: intimidate, extract, and disappear the evidence.

But as they expanded, they got sloppy. Lavish lifestyles drew attention. Dirty money flowed into legitimate businesses. And some wiseguys, believing themselves untouchable, forgot that banks, paper trails, and tax filings were not as easily silenced as street snitches.

The Rise of the Financial Investigator

Enter the accountants, auditors, and federal agents who understood one immutable truth: criminals need to spend money. And when they do, they leave footprints.

It was the Internal Revenue Service—not an elite hit squad—that brought down Al Capone. In 1931, “Scarface” was sentenced to 11 years in federal prison for tax evasion. The man who ran Chicago through fear and violence couldn’t explain his lavish lifestyle on a supposed income of $0.

This moment became a blueprint. While guns and wiretaps could only go so far, financial records told a clearer story—and they didn’t lie.

By the 1980s, the FBI was integrating forensic accountants into mob investigations. Operation Donnie Brasco (1976–1981), made famous by undercover agent Joseph Pistone, provided critical intel. But it was financial scrutiny that ultimately nailed dozens of made men.

The Commission Trial: When the Books Beat the Bosses

One of the most significant blows to the Mafia came with the 1985 United States v. Anthony Salerno case, better known as the Mafia Commission Trial. Led by U.S. Attorney Rudolph Giuliani, the trial targeted the heads of the Five Families of New York. They weren’t brought in on murder charges—but racketeering and extortion.

Giuliani’s team used RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act) to tie decades of crimes into a unified charge. At the heart of the case? Follow-the-money tactics: construction contracts, kickbacks, union pensions, and skimming operations.

Mob bosses had used “no-show” jobs and shell companies to extract millions. Through subpoenaed bank records and secret wiretaps, prosecutors laid out a criminal empire disguised as a business consortium. The trial ended with convictions for all eight defendants, sentencing them to 100 years each.

The message was clear: If the feds could follow the money, they could follow the power—and destroy it.

Vegas: From Mafia Mecca to Corporate Playground

Nowhere was the mob’s financial manipulation more visible than Las Vegas. In the ’60s and ’70s, crime families funneled millions into the Strip’s glitzy casinos—then siphoned profits off the top through a process called “skimming.”

The Chicago Outfit, the Kansas City Mob, the Cleveland family—they all had a piece of the action. But while flashy enforcers handled the floors, it was the quiet accountants that led to indictments.

The Strawman case (1979–1986) exposed the hidden ownership of casinos like the Stardust and the Tropicana. FBI agent Joe Yablonsky, who ran the Las Vegas Organized Crime Strike Force, led a team that traced fake loans, forged documents, and untraceable cash payments. In the end, more than 15 high-level mobsters were convicted—not for violence, but for the movement of unaccounted-for cash.

The Turncoats and the Paper Trail

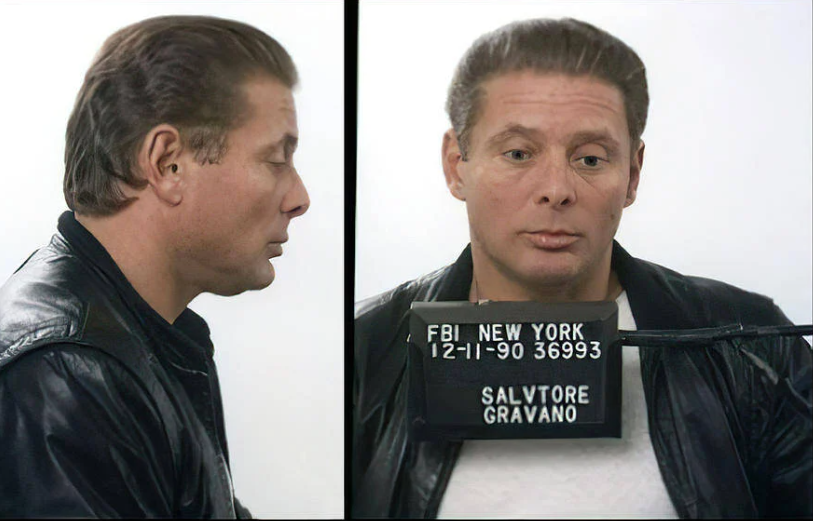

By the late ’80s, the golden era of the Mafia was crumbling. Law enforcement had learned to flip key insiders—mobsters who knew the books and the bodies. Sammy “The Bull” Gravano, underboss of the Gambino family, famously turned on John Gotti in 1991, offering detailed accounts of murders and money laundering.

But even without informants, investigators were learning to build airtight cases with QuickBooks and subpoenaed bank accounts. The mob’s dependence on cash businesses—pizzerias, waste management, construction—became their Achilles’ heel. Once digital banking emerged, their “invisible” economy started leaving fingerprints.

Modern Mobsters and Digital Laundering

Today’s organized crime doesn’t look like a scene out of Goodfellas. It’s quieter. Slicker. And more international.

The Italian ’Ndrangheta, Russian Bratva, and Chinese triads have embraced cryptocurrency, offshore shell corporations, and real estate investments. In 2020, Europol estimated that over 1% of global GDP—nearly $2 trillion—is laundered each year, often through legitimate-looking financial channels.

In one case, the Italian Mafia used Chinese shadow banks to move illicit proceeds through Milan fashion businesses and back to Calabria. In the U.S., federal agents have tracked fentanyl profits through anonymous crypto wallets and digital payment apps.

Still, the fundamental tactic remains: follow the money.

Conclusion: Numbers Don’t Lie—They Lead

The image of the mobster with a pinky ring and blood on his hands has faded. Today’s Mafia wears suits, uses encrypted messaging apps, and reads financial statements. But their weakness remains unchanged: greed. And greed generates paper trails—whether on bank statements, crypto ledgers, or property records.

The mob may evolve, but investigators evolve faster. And as long as there’s a dollar to be skimmed, there’s an auditor or agent prepared to chase it to hell and back.

The phrase “follow the money” is more than a cliché. It’s a doctrine. A sword. And in the war against organized crime, it remains the sharpest weapon of all.