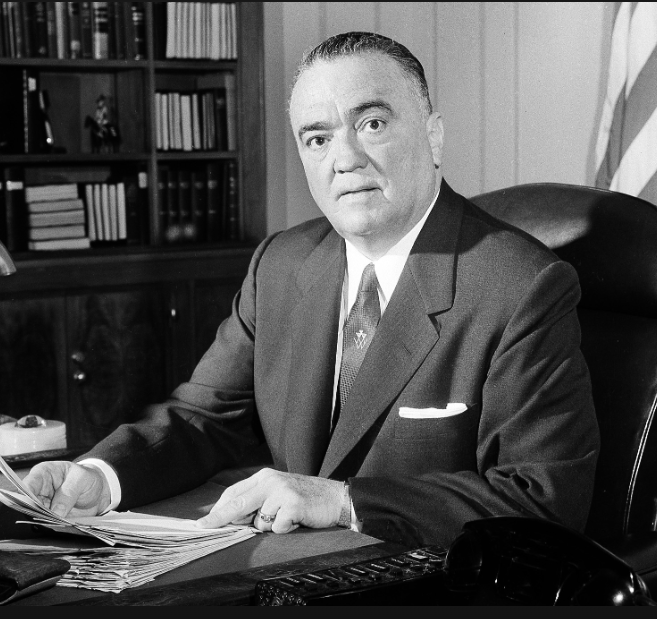

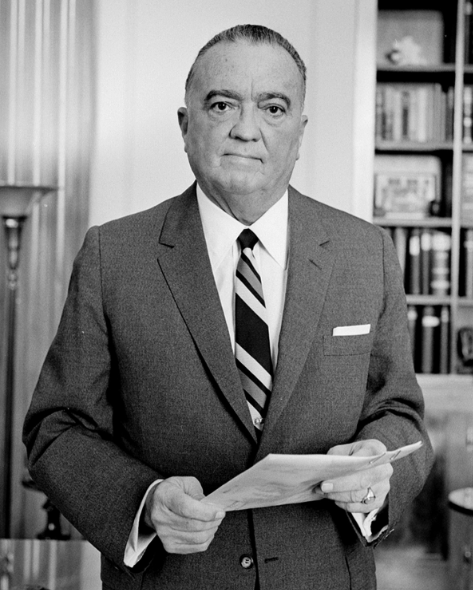

For decades, America’s top cop stood before Congress, the press, and the American people with a straight face and a steel jaw, insisting there was no such thing as the Mafia. While bullets flew in the streets of Chicago, bodies piled up in the Hudson River, and heroin flooded American cities via international crime syndicates, J. Edgar Hoover—the all-powerful director of the FBI—maintained his position with unshakable denial. “There is no organized crime in America,” he claimed, even as Mafia bosses dined with senators, infiltrated unions, and lined the pockets of judges, cops, and politicians alike.

It wasn’t ignorance. It wasn’t incompetence. It was a coverup.

Behind Hoover’s stony silence lay a calculated decision driven by self-preservation, not law enforcement. He wasn’t blind to the threat. He was afraid of it. More precisely, he was afraid of them. Not the Mafia bosses, per se—but of what they had on him.

Hoover’s Blind Eye: A Strategy or a Stalemate?

By the 1930s and 40s, organized crime was well on its way to becoming a multi-billion dollar industry, with families like the Genovese, Gambino, and Lucchese running rackets from coast to coast. The FBI, under Hoover’s control, focused obsessively on “public enemies” like John Dillinger and Alvin Karpis, while turning a deliberate blind eye to La Cosa Nostra.

Hoover’s refusal to acknowledge the Mafia was so out of step with reality it bordered on delusional—or, more accurately, deeply suspicious. The New York Times had run exposés. The Kefauver Hearings in 1950 laid out reams of testimony and evidence of an expansive national syndicate. Journalists like Walter Winchell and investigators in New York City and Chicago rang alarm bells louder than church bells on Easter Sunday. But Hoover? Silence. And more than silence—resistance. He actively downplayed and derailed investigations into organized crime, often punishing agents who tried to dig too deep.

Why?

The answer, whispered in Washington circles and now accepted by many historians, is blackmail.

The Secret Life of J. Edgar Hoover

Hoover wielded secrets like a weapon. He kept detailed dossiers on presidents, senators, civil rights leaders, and Hollywood icons. But the man who weaponized shame and scandal harbored a devastating vulnerability of his own: his alleged homosexuality.

In the mid-20th century, homosexuality was not only taboo—it was considered a security risk. And Hoover, the ever-immaculate figurehead of morality and patriotism, had a long and intimate relationship with his deputy, Clyde Tolson. The two dined together nightly, vacationed together, and were rarely seen apart. While there’s no confirmed proof they were lovers, it was certainly enough—enough to ruin a reputation, topple a career, and invite ruin in an era when being “outed” could mean social and political death.

The Mafia, always in the business of secrets and leverage, reportedly had the goods. Stories persist that mob-connected lawyer and fixer Roy Cohn (himself a closeted gay man and legal counsel to Senator Joseph McCarthy) helped the Mafia gather compromising photographs of Hoover at homosexual parties or with male companions. Cohn had close ties to mob bosses like Frank Costello and Meyer Lansky—and he knew the value of a skeleton in a closet, especially if it belonged to the man in charge of law and order.

Whether the blackmail was explicitly carried out or not, Hoover knew the Mafia could destroy him—and so, for years, he helped protect them by simply denying they existed.

Apalachin: The Meeting That Blew the Lid Off

Then came 1957. The sleepy upstate New York town of Apalachin became the accidental battleground for the FBI’s greatest lie.

Mob boss Joseph Barbara was hosting a gathering of high-ranking Mafia figures from all over the country. This was no small dinner party—it was a summit of the nation’s top crime lords. The guest list read like a who’s who of underworld royalty: Vito Genovese, Carlo Gambino, Joe Profaci, and over 100 others. Their agenda? Settle disputes, allocate territories, and discuss the growing heroin trade.

But local law enforcement got suspicious of all the expensive cars with out-of-state plates showing up at the Barbara estate. They set up roadblocks, and in a panic, dozens of Mafia leaders fled into the woods in silk suits and wingtip shoes, scattering like rats as police rounded them up.

News of the raid made national headlines. The Mafia wasn’t a rumor anymore—it was photographed, fingerprinted, and cornered in upstate New York.

Hoover had no choice but to acknowledge reality.

Under pressure from the media and Congress, the FBI scrambled to reframe its long silence. Agents were reassigned to start investigating organized crime more aggressively. By the early 1960s, Hoover launched the FBI’s “Top Hoodlum Program.” But the damage was done. The Apalachin meeting shattered his public denial and raised questions about why the FBI had failed for so long to act on mountains of evidence.

The Cost of the Lie

Hoover’s failure to act decisively against the Mafia allowed organized crime to grow unchecked for decades. The mob infiltrated Hollywood, hijacked labor unions, laundered billions through Las Vegas, and turned New York City into its personal playground.

The cost wasn’t just financial. It was moral. By prioritizing his own reputation over justice, Hoover let an empire of violence and corruption flourish.

More disturbingly, it proved that the nation’s most powerful law enforcement figure was not above being compromised—by fear, by shame, and by those willing to exploit it.

A Legacy Stained

Today, Hoover’s name still graces the FBI’s Washington headquarters. But the man behind the myth is no longer viewed as an incorruptible patriot. His paranoia, vindictiveness, and alleged double life paint a picture of a man who projected strength while harboring profound fear.

He built his empire on surveillance, secrecy, and leverage. And in the end, it was those very tools that undid his credibility.

The Mafia never needed to kill Hoover. They didn’t need to bribe him. They just had to know.

And that knowledge was power enough to keep America’s top cop looking the other way.