In the smoke-thick halls of mid-century American prisons, silence wasn’t safety. It was the sound of a deal gone wrong, a warning issued through the slits of iron bars, or a pulse that suddenly stopped in the night. From the 1940s through the 1960s, a chilling pattern haunted America’s penal institutions: mob-connected prisoners, informants, and inconvenient witnesses dying under “questionable” circumstances. Whether by overdose, suicide, illness—or quiet murder disguised as all three—death came swiftly and selectively to those who crossed the Mafia.

Peter LaTempa: Poison in the Cell

Peter LaTempa’s story reads like the first act of a mob opera—one that ends before the curtain rises. A small-time mobster with ties to Vito Genovese, LaTempa agreed to testify against his former boss in 1945. He was set to corroborate the testimony of Ernest “The Hawk” Rupolo, who had already implicated Genovese in the 1934 murder of Ferdinand “The Shadow” Boccia.

The state knew the risk. LaTempa was placed in protective custody in Raymond Street Jail, a supposedly safe haven. But in June of 1945—just before the trial—LaTempa died suddenly in his cell. The official cause: a massive overdose of barbiturates. Yet investigators were stunned to find the drugs had not been prescribed to him. According to a 1945 New York Times report, prison officials couldn’t determine how the poison entered his system.

Genovese walked free, grinning like a cat that had devoured the canary. LaTempa’s body was buried, but his death echoed as a warning. In the Mafia’s rulebook, betrayal wasn’t just punishable—it was permanent.

Abe Reles: The Canary with Clipped Wings

Few nicknames in Mafia lore are as ironic as that of Abe “Kid Twist” Reles. A contract killer turned government informant, Reles was a key witness against the notorious Albert Anastasia, head of the brutal enforcement arm Murder, Inc. Reles had already testified against several major players and was being kept under tight supervision at the Half Moon Hotel in Coney Island—protected by a phalanx of armed guards.

On November 12, 1941, just hours before he was to testify against Anastasia, Reles “fell” from a sixth-story window. Authorities were quick to rule it a botched escape attempt, claiming he had tried to climb down a series of tied bed sheets. But the story didn’t hold up. The drop was clean, without any evidence of a failed descent. The FBI and NYPD offered a $50,000 reward for information on Reles’ death, but the silence was deafening.

The message was unmistakable: even surrounded by guards and state protection, the Mafia could reach you. Reles had sung too loudly—and someone had pulled the plug.

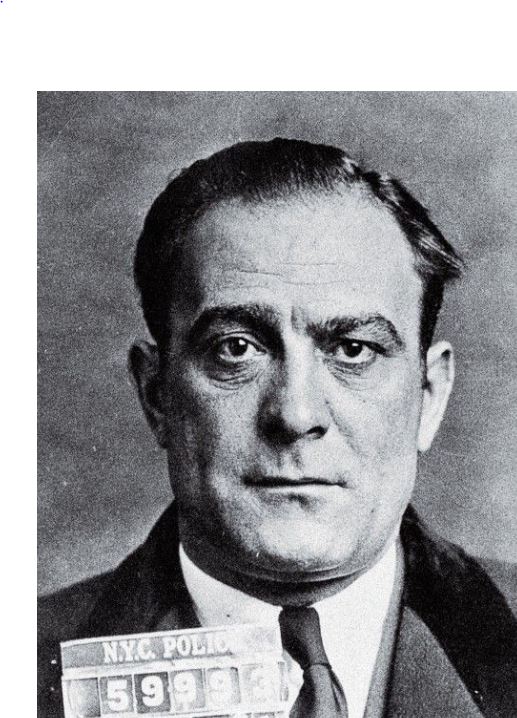

Johnny Dio’s Quiet Reach: Union Enemies Silenced

John “Johnny Dio” Dioguardi was one of the most dangerous men to wear a suit in mid-century America. As a labor racketeer, Dio orchestrated industrial strikes, acid attacks, and assassinations. His enemies didn’t just disappear—they ended up disfigured, brain-damaged, or dead in a padded cell.

In 1956, journalist Victor Riesel, a crusader against union corruption, was blinded by acid in broad daylight. Though Dio was convicted, witnesses against him often changed their minds, fled, or died. One such figure, a union courier known only as “Joe M.,” died in jail while awaiting a court date. Officially, it was a suicide. Unofficially, he’d been receiving threats for weeks and begged for a transfer that never came.

Dio’s reach inside the system was long, even while behind bars. He bribed guards, planted enforcers in prison kitchens and laundry rooms, and ensured that enemies felt his presence long after they thought they were safe.

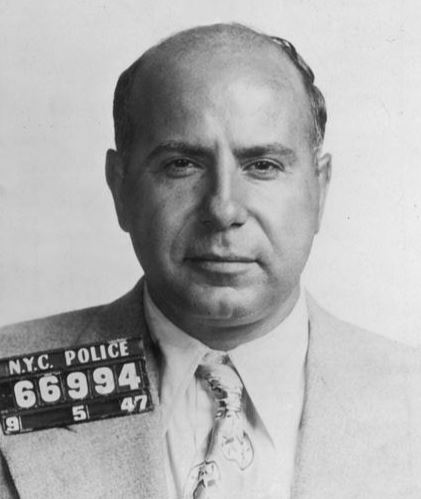

Carmine Galante: Chainsmoke and Silence

Before he was gunned down in a Brooklyn backyard in 1979, Carmine “Lilo” Galante was already feared as a bloodthirsty enforcer and narcotics kingpin. But during the 1950s, while locked up on drug trafficking charges, Galante was suspected of orchestrating the deaths of two inmates who had been cooperating with the feds in narcotics cases tied to the Bonanno family.

One of them, Salvatore “Little Sal” Bonfiglio, was stabbed in the prison library in 1958. His killer was never found. Another, a low-level courier named Joseph Russo, died of what prison doctors called a “severe allergic reaction” during dinner in 1957. His family insisted he had no such allergies. Rumors swirled that Galante had corrupted kitchen staff, a common mob tactic at the time.

Despite his imprisonment, Galante acted like a warden of his own criminal empire. He controlled the movement of contraband, the distribution of commissary goods, and the fate of anyone who dared turn on La Cosa Nostra.

Frank Costello’s Quiet Pressure

Though often portrayed as the “gentleman gangster,” Frank Costello knew the value of intimidation. After surviving an assassination attempt in 1957, Costello stepped back from power but not influence. Multiple informants who had agreed to testify against him—particularly in Senate hearings about organized crime—either recanted or were found unfit to testify due to sudden mental illness or mysterious injuries sustained behind bars.

In one such case, a low-level accountant for a front company linked to Costello was found catatonic in his cell in 1959, his mind shattered by what doctors said was a “trauma-induced psychosis.” Fellow inmates whispered of late-night beatings and food laced with tranquilizers. No charges were ever filed.

Final Thoughts: Death Comes in Shadows

The prisons of the 1940s to 1960s were not sanctuaries for the state’s witnesses. They were hunting grounds for the Mafia. Guards were paid off, doctors turned blind eyes, and prisoners—many of them soldiers still loyal to the Mob—acted as silencers behind bars. Whether through poisoned pills, suspicious falls, or arranged suicides, the Mafia ensured that betrayal didn’t live long. The chilling truth is that many of these deaths were never properly investigated. Files went missing. Autopsies were inconclusive. The machinery of justice, when greased by the right palms, often ran backward. In a world where a whisper could be fatal and a favor owed was a debt of blood, prison wasn’t protection. It was a waiting room—for the grave.