In the shadowy underworld of 1950s organized crime, there was no address more whispered about—or more fiercely protected—than 73 Palisades Avenue, Cliffside Park, New Jersey. At first glance, Duke’s Restaurant looked like a thousand other Italian eateries across the tri-state area: red-checkered tablecloths, the hum of Sinatra overhead, and the rich aroma of garlic and veal wafting from the kitchen. But behind the warm, familiar façade was a fortress of secrets. And seated at its core was one of the most enigmatic and feared mobsters of the era: Joe Adonis.

To the uninitiated, Duke’s was just a neighborhood joint. To the underworld, it was the Mafia’s Cabinet Headquarters—a nerve center of national organized crime. Lawmen and journalists alike dubbed it the Mafia White House, but that understated the truth. The real power didn’t lie in titles; it sat behind a soundproof, steel-clad icebox door, hidden in the rear of the restaurant. Behind that door was the “control room,” the strategic war room where hits were ordered, rackets were divided, and mobsters were tried and sentenced by their peers.

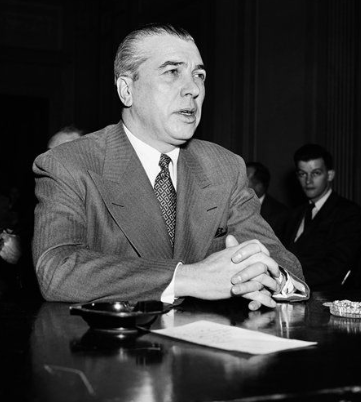

Presiding over these high-level summits was Joe Adonis, born Giuseppe Antonio Doto in Naples and raised in the criminal crucible of Brooklyn. A dashing, disciplined figure with movie-star looks and ice-cold resolve, Adonis wasn’t just a capo—he was a kingmaker. His influence stretched from Jersey to Havana, and from local unions to the glittering casinos of Las Vegas. And Duke’s was his throne room.

Tuesdays of Terror

While the pasta and cannoli kept the front of the house busy, it was Tuesday afternoons when things truly turned sinister. That’s when the so-called “Big Six”—America’s criminal elite—converged on Duke’s for their weekly meetings. These weren’t casual lunches; they were national security briefings for the criminal state.

Flying in from Chicago were Tony “Joe Batters” Accardo and his lieutenant, the greasy but lethal Jake “Greasy Thumb” Guzik, representing the formidable Chicago Outfit. Meyer Lansky, the criminal financier whose reach extended from Saratoga to the Caribbean, would arrive quiet and precise, a briefcase full of numbers and ledgers. Frank Costello, the “Prime Minister of the Underworld,” held court on behalf of the then-imprisoned Lucky Luciano. New Jersey’s own Longy Zwillman, with his hands deep in state politics, including the appointment of governors and attorneys general, came to protect local interests. And of course, Joe Adonis sat at the head, the host and unofficial moderator of this deadly roundtable.

In that sealed-off room—impervious to wiretaps, bugs, or bullets—American organized crime was governed.

A City Within a City

Duke’s wasn’t just protected by its thick walls. It was protected by layers of local complicity. Law enforcement from Manhattan had to cross the George Washington Bridge to reach Cliffside Park. Once they crossed into Jersey, many reported being tailed by unmarked cars, hassled by local cops, or outright arrested on suspicious pretenses. It was as if Duke’s existed in a foreign nation—one run by mob diplomacy and municipal sabotage.

Federal agencies such as the IRS, the Bureau of Narcotics, and the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office all tried to get a foothold. Surveillance teams set up across the street were routinely forced to leave by local police, who seemed more intent on shielding the mob than enforcing the law. Duke’s was more than a restaurant—it was a no-go zone for justice.

Kefauver Cracks the Illusion

Duke’s prominence would eventually draw the attention of the Kefauver Committee, a Senate investigation into organized crime that captured the public imagination in the early 1950s. Televised hearings gave ordinary Americans their first look at the nation’s underworld, peeling back the myth to reveal a shadow government run by men like Adonis, Costello, and Lansky.

But Duke’s was slippery.

When questioned, gangster Willie Moretti told the committee—deadpan—that he went to Duke’s only “for the cuisine and the ambiance,” comparing it to Lindy’s on Broadway with a smirk. Tony Bender, another high-ranking mobster, took the Fifth Amendment rather than even acknowledge he’d ever stepped foot in the place, noting that such an admission could be incriminating.

The committee left with hints but no handcuffs, and Duke’s carried on—for a while.

A Kingdom Crumbles

The scrutiny brought by Kefauver changed everything. Adonis, already under pressure from law enforcement, was deported to Italy in 1956. His power base disintegrated. Without him, Duke’s lost its iron ring of protection. The mob, ever mobile and paranoid, relocated their operations to quieter, less conspicuous venues. The infamous Tuesday meetings ceased. And without the draw of danger and power, the food alone couldn’t save the restaurant.

Duke’s closed not long after.

The vacuum left behind was palpable. Some syndicate figures, like Willie Moretti, moved their meetings elsewhere—namely to Joe’s Elbow Room, just a few blocks away. But that too would prove fatal. In 1951, Moretti was shot in the head at close range during lunch, silenced by his own crew in a so-called “mercy killing.” He had become too talkative, too erratic—too dangerous.

The walls of Duke’s never spoke, but the deadly silence that followed said enough.

Ghosts in the Dining Room

Today, the site that once housed Duke’s has been wiped clean. A residential high-rise now stands on the bones of the Mafia’s most important East Coast command post. There are no plaques, no historic markers, no recognition of what transpired in that ordinary-looking building in Cliffside Park. But to historians of organized crime, Duke’s remains hallowed ground—a symbol of how the mob once operated in plain sight, using a fork in one hand and a dagger in the other.

It was never just about food. It was about power cloaked in familiarity. Behind every order of spaghetti marinara was an empire built on extortion, violence, and silence. Joe Adonis didn’t just run a restaurant. He ran a nation without borders, a criminal confederacy whose reach extended to the very edges of American life.

In the end, Duke’s was more than a restaurant. It was a cathedral of crime, a place where the faithful came to worship not God, but Greed, Loyalty, and Fear.

And like all cathedrals, its legacy outlives its stones.

Written by: C.F. Marciano