The Twisted Tale of Martin T. Manton, Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, and the Most Corrupt Courtroom in U.S. History

THE BLACK-ROBED DECEPTION

We like to imagine judges as incorruptible—monastic figures draped in black robes, untouched by greed, politics, or the stench of the streets. But history, dark and cruel, reminds us otherwise. Long before modern headlines of justices accepting luxury trips and gifts, there was Martin T. Manton—once revered, now rotted in memory.

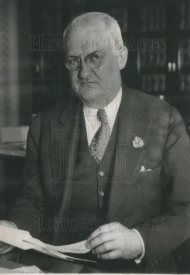

Manton was not just another robe behind a bench. From 1918 to 1939, he served on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York, one of the most powerful judicial posts in the country. At his peak, he was whispered to be the “tenth Justice,” one step away from the Supreme Court. A Columbia Law graduate, honored by universities and even knighted by the Pope, Manton carried an aura of righteousness. But beneath the polish lay rot—and that rot reached deep into the veins of organized crime.

THE BUSINESS OF JUSTICE

Behind the mahogany bench, Manton operated a dark empire. Courtroom by day, criminal enterprise by night. He raked in the modern equivalent of $17 million through bribes, “loans,” and kickbacks from desperate litigants, eager lawyers, and, most chillingly, the Mafia. He didn’t just take money—he took sides, penning decisions that favored whoever fed his coffers.

With every signature, justice was sold.

And Manton’s clientele wasn’t limited to corporate titans or Wall Street elites. Among his most notorious benefactors were the underworld kings of New York: Louis “Lepke” Buchalter and Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro. These were not just criminals. They were murderers, racketeers, architects of death. And Judge Manton opened the gates of justice for them—for a price.

LEPKE BUCHALTER: THE MOB’S GOLDEN TICKET

Louis “Lepke” Buchalter, the head of the feared Murder, Inc., had blood on his hands and the law at his heels. But what he also had was money—and Martin Manton’s weakness for it.

Facing charges and the looming threat of prison, Lepke needed a miracle. He got Manton. Documents and FBI files later revealed the Mafia’s direct line into the judge’s chambers. For the right price, Manton arranged favorable rulings and—most egregiously—secured bail for Buchalter and Shapiro. The moment they walked free, they unleashed violence, killing witnesses, silencing enemies, and tightening the Mob’s grip on New York. Tammany Hall boss Jimmy Hines once bragged, “He’s the only federal judge left in New York we can use to get people out of jail.” That judge was Manton. He didn’t just betray the bench—he enabled murder.

THE ROTTEN CORE OF POWER

Manton’s corruption went far beyond Lepke. His decisions warped the outcomes of major corporate battles, railroad fare lawsuits, patent disputes, and criminal trials. Each verdict was a transaction.

Cash payments were slipped through middlemen, stuffed into envelopes, hidden in courtroom safes. Some bribes were disguised as “loans,” never repaid. Others were more lavish—vacation trips paid by litigants, contracts awarded to his family members, or business interests steered to companies he secretly owned.

He wasn’t alone. A tangled web of fixers, lawyers, and even fellow judges played along, facilitating the betrayal of the system. Even elite law firms and top lawyers, like Thomas Chadbourne of Chadbourne Parke, turned a blind eye or helped broker the deals. The legal aristocracy fed off the decay.

ALMOST SUPREME

In 1922, Manton nearly ascended to the U.S. Supreme Court. President Warren Harding considered him a frontrunner—especially for what was then whispered as the “Catholic seat” on the Court

But Chief Justice William Howard Taft blocked him, sensing something off, something rotten. Taft’s resistance saved the highest bench from an infestation—but it didn’t stop Manton’s reign in the Second Circuit. For over a decade more, he bent justice to his will, ruling over lives, fortunes, and fates with a pen oiled by bribes.

THE FALL

By the late 1930s, whispers turned into roars. Manhattan District Attorney Thomas E. Dewey had his eyes on Tammany Hall’s cancer—and Manton’s name kept surfacing. But it wasn’t the FBI or Justice Department that brought him down. It was a dogged reporter at the anti-Tammany New York World-Telegram who finally exposed the rot.

The Justice Department, embarrassed and cornered, had no choice. In 1939, after a trial in the very courthouse he once ruled, Manton was convicted of conspiracy to obstruct justice.

He had called in favors from political titans—former presidential candidates Alfred Smith and John W. Davis testified for his character. But the jury wasn’t swayed. Manton was sentenced to two years in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary. He served 17 months, and died disgraced.

THE JUDGE WHO NEVER REPENTED

To the very end, Manton claimed innocence. His defense? That he would’ve ruled the same way even without the money. But the court that sentenced him saw through the lie. “Judicial action, whether just or unjust, is not for sale,” it declared.

He left behind a shattered legacy and a warning burned into the bones of American law: no one—no matter how robed, educated, or honored—is immune from corruption.

Manton wasn’t just a judge gone bad. He was the living embodiment of systemic rot—of what happens when unchecked power meets organized crime. He was the judge who sold justice to the highest bidder, and his most valuable clients were killers.

LEGACY OF DECAY

Today, new ethics rules and financial disclosures are designed to prevent “another Manton.” But no rulebook can stop a man like Martin Manton if the system sleeps. His tale, stained by blood money and betrayal, reminds us that even the pillars of justice can be hollow—and inside, the mob may still whisper.

When judges rule from the shadows, and gangsters walk free, the price isn’t just a verdict. It’s democracy itself.

By C.F. Marciano – The Godfather of Gritty Tales