On January 10, 1952, an event steeped in grandeur and divine reverence unfolded in Rome. Pope Pius XII blessed two gold crowns encrusted with 500 diamonds and other precious stones. These opulent symbols of faith, destined for the Regina Pacis Votive Shrine in Brooklyn, were not merely artifacts; they were beacons of hope and devotion for a community that poured its wealth and faith into the shrine. Parishioners had contributed their cherished jewelry—rings, brooches, necklaces—to create these crowns, a physical embodiment of collective reverence. But within months, this sanctified offering became the centerpiece of a tale dripping with crime and shadows.

In a brazen act of sacrilege, two opulent gold half-crowns, insured for $o10,000 and encrusted with over 100 dazzling diamonds and other precious stones, were stolen from the Regina Pacis (Queen of Peace) Votive Shrine at 12th Avenue and 65th Street in Brooklyn. These sacred relics had adorned a painting of the Madonna and Child behind the altar, their brilliance a symbol of faith and devotion. But under the cover of night, a cunning thief stripped them from their rightful place, leaving a community reeling.

The meticulous heist unfolded with chilling precision. The thief, likely tall and exceptionally agile, sawed through a protective bronze grille positioned five feet eight inches above a ledge. Reaching a foot further, the intruder deftly removed the crowns from the painting. Police theorized that the perpetrator had hidden within the church before it was locked at 9:45 p.m. Friday night. He is believed to have escaped through one of several fire escape doors, designed to open from the inside. Despite the presence of an electric alarm system, controlled by a switch housed in the shrine’s safe, the mechanism failed to sound. The mystery deepened as investigators pieced together the thief’s daring path.

The Madonna and Child painting, a towering six feet high and four and a half feet wide, rests in a niche ten feet behind the altar. To access it, the thief climbed two four-foot stone ledges and ascended a series of steps. Using a hacksaw or similar tool, he cut away a decorative rosette in the grille, leaving a narrow six-by-four-inch opening. This allowed him to reach inside and retrieve the crowns, which were mounted on small metal pegs to give the illusion that the figures in the painting were wearing them. Each crown, flat on one side for this purpose, was a masterpiece of craftsmanship—now reduced to stolen treasure.

The theft has sent shockwaves through the parish, leaving both police and parishioners searching for answers. As prayers for the crowns’ return echo through the shrine, the audacious crime stands as a stark reminder of vulnerability, even in sacred spaces.

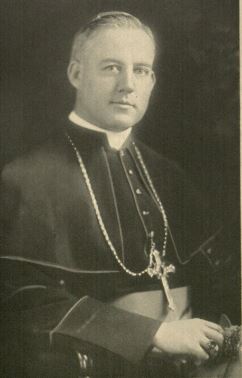

The crime, decried by Archbishop Thomas E. Molley as “a dreadful sacrilegious action,” ignited a storm of prayers and investigations.

Detectives scoured Brooklyn for clues, their attention drawn to a green sedan ominously parked near the shrine on the night of the theft. But as theories swirled, so did the whispers of darker forces at play. Enter Joe “Olive Oil King” Profaci, a man whose name was spoken in hushed tones in Brooklyn’s underworld. Profaci, a devout Catholic and benefactor of the church, was incensed. His sons attended the church along with his wife and other family members. To him, the theft was not just a crime against a shrine but an affront to the sacred.

The police had theories, but Profaci had solutions.

On June 4, 1952, the bullet-riddled body of Ralph “Bucky” Emmino, a 33-year-old jewel thief with a reputation as bold as his flashy lifestyle, was discovered discarded on a weed-choked sidewalk in Bath Beach. Known as the “gangsters’ graveyard,” the desolate area bore silent witness to yet another tale of underworld retribution. Emmino had been executed in classic mob style—shot twice in the chest and once in the head. Powder burns on his body revealed the shots were fired at close range, marking a cold and deliberate killing.

Authorities were quick to theorize that Emmino’s violent end might be connected to the theft of the $100,000 jeweled crowns stolen from the Regina Pacis Shrine just days earlier. Inspector Thomas Hammill acknowledged, “There is no evidence as yet of direct connection with the theft of the jewels, but the investigation is being pursued along those lines.” Emmino’s criminal record was as ostentatious as his 1950 green Pontiac convertible, registered under the name of his wife, Lilliam Morondo. Witnesses reported seeing him drive off in the vehicle the night before his death, at precisely 7:41 p.m., leaving behind more questions than answers.

The discovery of Emmino’s body came through an anonymous phone call, a chillingly brief message that led police to Bay 41st Street, between Bath and Benson Avenues. For law enforcement, the scene was another grim reminder of Bath Beach’s violent legacy. While investigators scoured for clues linking Emmino to the shrine heist, the broader implications of his death sent a clear message to Brooklyn’s underworld: betrayal—or mere suspicion of it—carries a deadly cost. As speculation swirled, one thing became certain: Emmino’s name would be added to the grim ledger of mob justice, his life extinguished in a shadowy struggle for control and retribution.

Then, a week later, the miraculous happened. Or so it seemed. The crowns were returned via U.S. mail, stuffed unceremoniously into a brown manila envelope and addressed to church where the crowns were stolen. The return address was the police headquarters annex on Broome Street. The crowns arrived slightly bent and missing jewels worth $3,000. Monsignor Angelo Cioffi declared it a divine act: “The Blessed Mother has heard our prayers. A miracle has happened.” Yet beneath the veneer of faith lay a darker truth.

Rumors whispered that Profaci’s “miracle” was no act of divine intervention but the brutal efficiency of mob justice. Though he publicly denied that Emmino had been strangled with a rosary, as some rumors claimed, Profaci did not shy away from admitting his involvement. The crowns’ return, though celebrated as a triumph of faith, bore the unmistakable imprint of underworld influence.

Profaci’s story did not end with the crowns. As head of the Colombo crime family, he would remain a figure of power and piety until his death of natural causes. His funeral, held at the very Regina Pacis Shrine he had defended, was a spectacle rivaled only by the obsequies of slain gangster Frankie Yale. The High Requiem Mass, celebrated by Rev. Salvatore Anastasio (brother of Albert “The Lord High Executioner” Anastasia), painted a picture of a man both feared and revered.

The Regina Pacis robbery stands as a tale of contradictions—devotion and desecration, faith and fear, the sacred and the profane. In the end, the crowns were returned, slightly tarnished but intact. Yet the events left an indelible mark, a reminder that even in places of peace, darkness can find a way in. And when it does, figures like Joe Profaci emerge from the shadows to reclaim what was lost—by any means necessary.

Penned by the Infamous C.F. Marciano – A Name You Don’t Forget